High-street fashion is in a stir. For the first time, one of the world’s four largest fashion houses, Stockholm-based H&M, has a woman at the helm. But it’s not only gender that marks out Helena Helmersson, it’s her CV.

Helmersson has bounced around a number of functions during her 22-year career at H&M. After a stint in purchasing, she has completed spells in human resources in Bangladesh, global production in Hong Kong and, most recently, as operations chief back in Sweden.

Yet, her star really began to shine during time as the brand’s head of sustainability between 2010 and 2015. She won plaudits for helping blaze a trail for greater circularity through recycling and reuse of garments. On her watch, H&M’s use of sustainable cotton more than tripled and the volume of used clothes collected from stores quadrupled.

But it wasn’t all roses. Most notably, her time overlapped with the high-profile collapse of a clothing factory in Dhaka, killing more than 1,100 workers and raising serious questions about labour standards in the supply chain. H&M was not directly involved, but as a significant procurer from Bangladesh, it felt the reputational fallout.

Helmersson’s stellar rise indicates that the C-suite is, at long last, opening its doors to sustainability. But what does this mean for the current crop of sustainability leaders? And how, if at all, might it reshape future boardrooms?

Sustainability leaders: more hard-headed

For sustainability leaders, H&M’s decision is welcome, but some perspective is required. C-suite recruiters are not about to start searching sustainability departments for their next chief executive hire.

That’s the view of Mike Barry, at any rate. He should know. For nearly 15 years, he headed up sustainable business at UK retailer Marks & Spencer. During that time, he saw social and environmental issues occupy increasing amounts of boardroom time and headspace.

Leaders need to be less of a scientist or spokesperson, and more engaged in what the business does and how it does it

Until now, sustainability professionals have overwhelmingly been subject experts, Barry notes. Typically, they would start out as environmental managers, as he did, and slowly move their way up. Now that’s all changing.

Sure, sustainability leaders must be on top of their brief, he says. But they also need to be commercially minded and knowledgeable about core business, as comfortable with a profit-and-loss statement as a carbon emissions’ chart.

“Today’s chief sustainability officer needs to be less of a scientist or spokesperson, and much more engaged in what the business does and how it does it,” he argues.

For the current cadre of sustainability leaders, this may well mean upskilling. Previously, a basic familiarity with core business management, including marketing, innovation, operations, organisation performance and so on, was sufficient. Now, only a thorough grasp will do.

Helping broaden leaders’ skillset

It’s a trend that Sophie Walker, UK head of sustainability at global professional services company JLL, is well aware of. On joining the UK plc board in January, after five years on the executive team, she approached the firm’s chief financial officer to help her get up to speed on the fundamentals of corporate finance.

But upskilling existing sustainability leaders is not the only option. Another is to rotate experts from other core business functions into board-level sustainability positions. In addition to the hard-edged business acumen they offer, they can bring a strong dose of commercial credibility to the role.

It is a tactic that ING has used with great success. When the Dutch bank was on the hunt for a new sustainability director five years ago, it opted for a complete newbie. Prior to his appointment, Léon Wijnands had worked almost exclusively in sales and customer services. Sustainability, he initially imagined, was something people did alongside their real job.

Experience quickly taught him otherwise. Under pressure from environmental campaigners, climate-concerned investors and financial regulators, Wijnands ordered a root-and-branch assessment of the climate risks inherent within the bank’s loan portfolio.

Five years on, he is as conversant as any sustainability nerd on stranded assets and climate-related financial disclosures. More importantly, under his direction, ING is now driving forward an industry-wide initiative to encourage the banking sector to align its future lending with global climate goals.

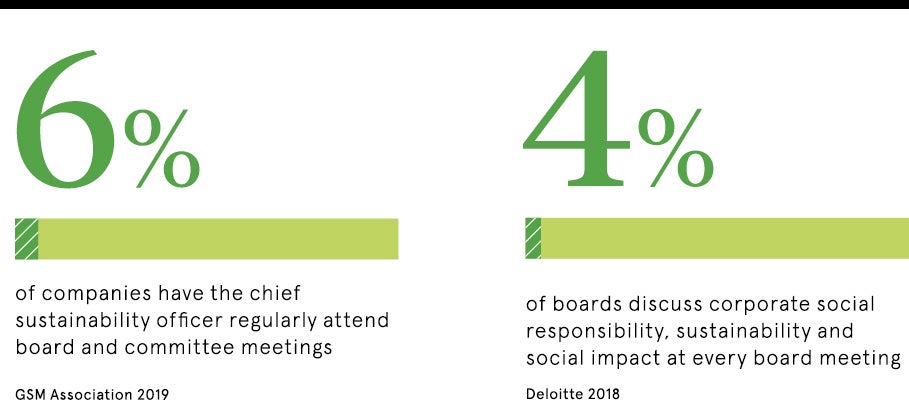

Building board expertise

ING hasn’t given up on turning off the office lights or giving to charity. But what Wijnands’ commercial mindset brought to the board was a sense of how sustainability fits into the bigger strategic picture, the financial risks the subject represents, the market opportunities it presents and the macro-trends it taps into.

“The key impact that you can create as a leader in a company is to integrate sustainability into the DNA of your department or your business unit or, ideally, the whole organisation,” he says.

The sentiment precisely echoes the thoughts of Catherine Harris, a New York-based sustainability specialist with recruitment firm Acre. Harris is author of a recent whitepaper that calls for companies to rejig their governance structures to “bring the voice of society” into the boardroom.

Creating a so-called social board can be achieved through a variety of mechanisms, she suggests. Notably absent from her list is reliance on a specialist sustainability department, as is the current norm. The issues at stake are now simply too broad, and too strategically important, to be palmed off.

Instead, just as sustainability leaders are having to brush up their core business competencies, so too board members must get up to speed on sustainability issues. Options vary, ranging from periodic board-wide briefings to intensive, individual training.

An organisation offering the full gamut is the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL). Linked to Cambridge University, this specialist centre reports a huge rise in demand over recent years for board education.

The rise of the “social” c-suite

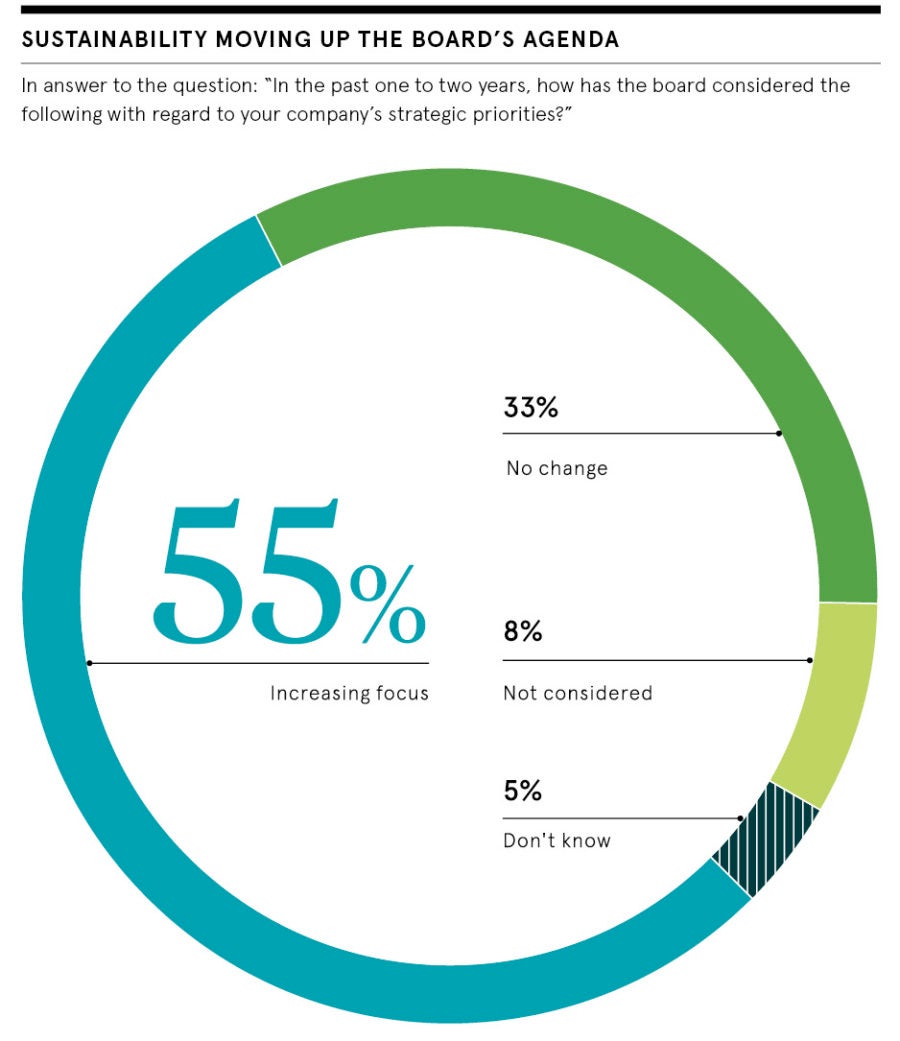

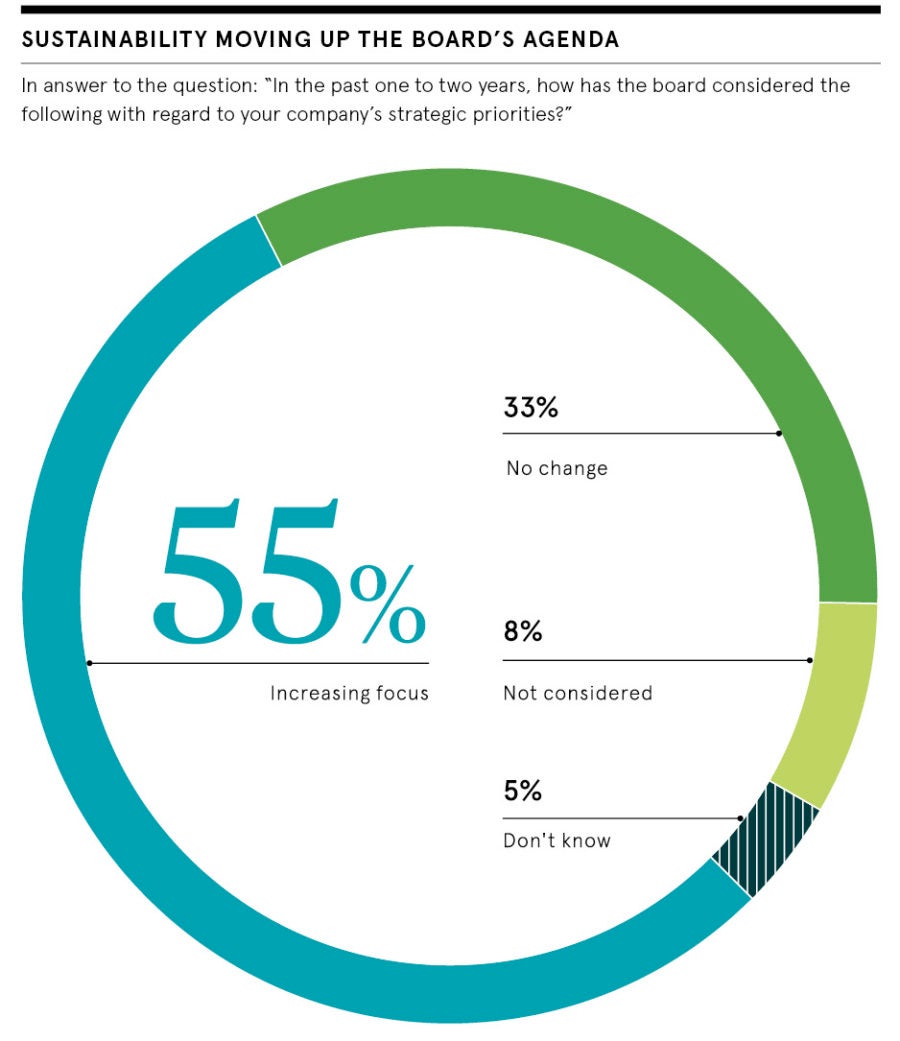

Not only are sustainability issues now seen as critical to future business growth, says CISL’s executive director of education Lindsay Hooper, but stakeholder demands on boards are also ramping up dramatically.

People are looking to business leaders not just to be “less bad”, but to come up with real solutions to big sustainability challenges. If top executives can’t respond when put on the spot, “then they are going to be on the back foot”, Hooper argues.

Walker at JLL is alert to this changing dynamic. Last September, she arranged for the company’s UK senior management team to attend a two-day bespoke course about sustainability leadership at CISL.

Her fellow executives didn’t emerge as overnight experts, she concedes, but they did come back with fewer fears and uncertainties about the subject. The experience left them with a greater level of comfort about “what they know and what they don’t know”, she observes.

Harris’s vision for a social board supports calls for stakeholder advisory panels. Made up of external subject experts, the role of such panels is twofold to point out flaws in a company’s existing practice and to make boards aware of emerging trends that could feasibly impact the business.

Consumer goods giant Unilever, which is regularly ranked as one of the world’s top sustainability leaders, boasts such a panel. The seven-member advisory council includes a world-renowned expert in human rights from Harvard, the conservation director at global environmental charity WWF and a former sustainability tsar for the UK government.

The panel’s official role is to guide and critique Unilever’s overarching sustainability strategy. The company’s head of sustainability Rebecca Marmot puts it more bluntly, describing its members as “critical friends” to the chief executive and his senior team.

Back to board basics

Whether fashion or finance, retail or consultancy, every business sector now finds itself in the sustainability firing line these days. The planet is under strain and big business is an obvious, and far from guiltless, target of blame.

But people also want answers. If the private sector is going to contribute meaningfully, then sustainability leaders and the C-suite need to shift tack with more business know-how for the former and greater sustainability expertise for the latter.

Crucial as a C-suite shake-up certainly is, the central function of company boards remains the same. To quote Peter Truesdale, director at consultancy firm Corporate Citizenship: “This isn’t about saving polar bears.” Instead it’s about business leaders better identifying sustainability-related risks and opportunities, and factoring them into corporate strategy.

Done well, companies will stand an infinitely better chance of thriving in the future. So, hopefully, will the bears.

Sustainability leaders: more hard-headed

Helping broaden leaders’ skillset