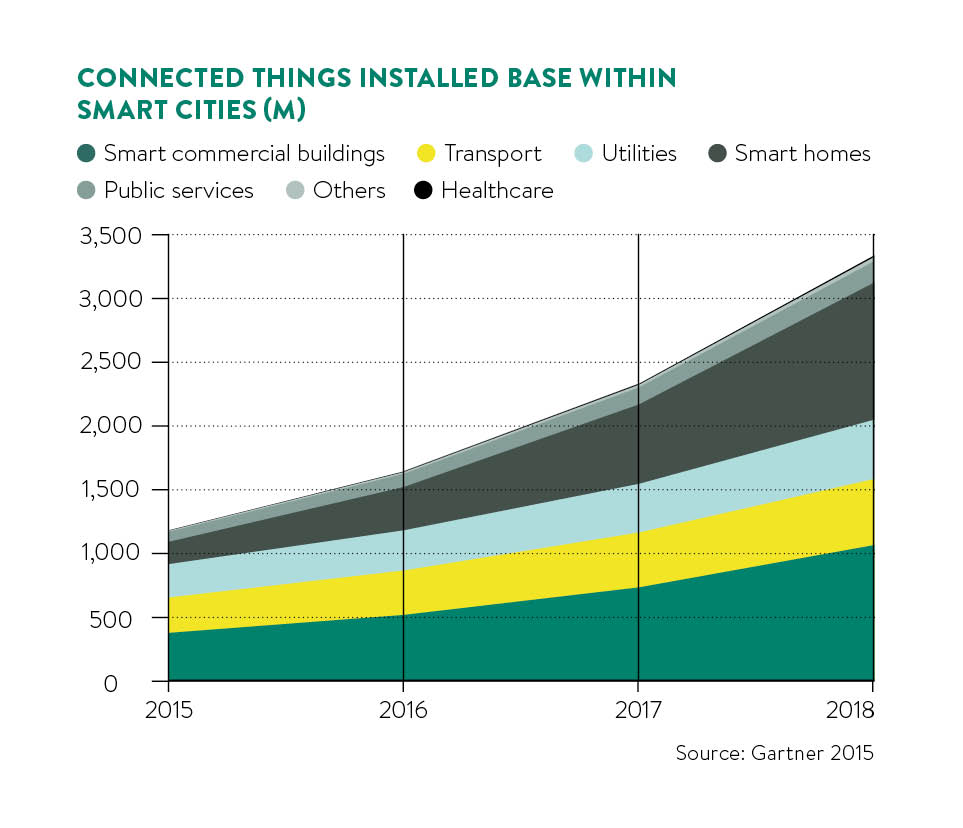

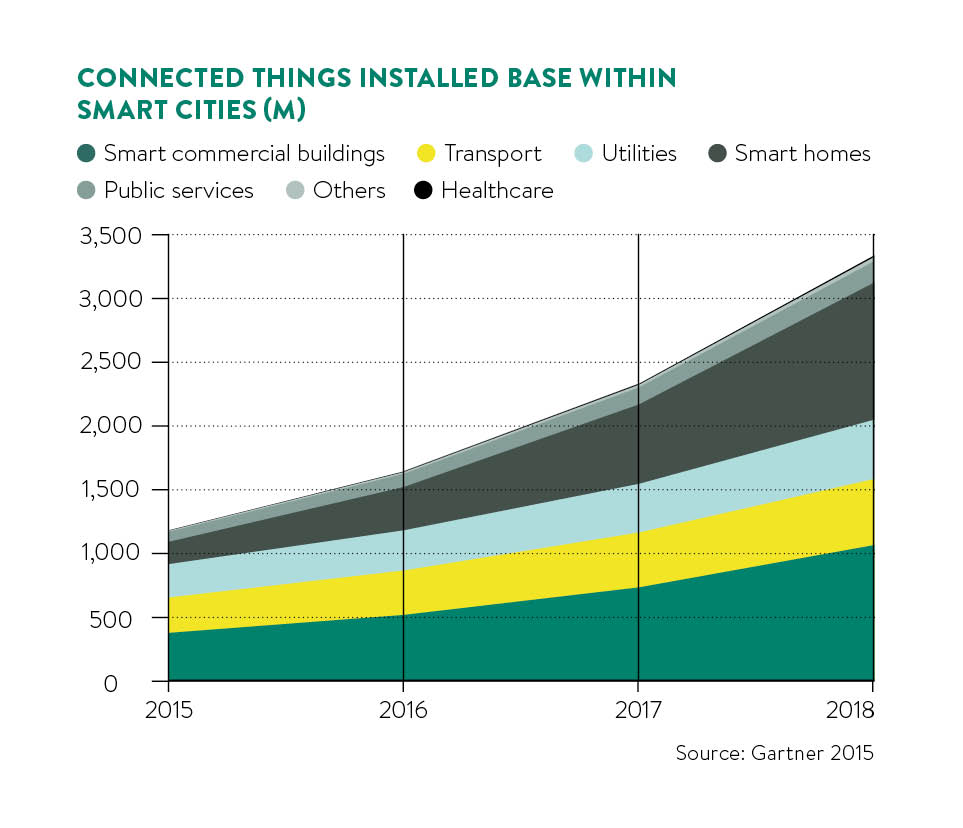

Smart can mean a connection to an ecosystem of devices, software and services. With smart cities, the internet of things – devices that collect and transmit data via the internet – will make cities more energy efficient.

Each smart city concept is different. There’s the ambitious projects to build shiny new things on green fields or in the desert, all hooked up to anything digital. Or there’s the challenge of retrofitting technology in established cities to make them more dynamic places. In all cases, technology aims to manage the urban environment better.

Learning from Masdar

One of the more renowned smart cities is Masdar in Abu Dhabi. It is built on a raised platform where water pipes with sensors and a fibre optic network sit below. Above ground, it features driverless cars and energy-efficient buildings with cooling technologies to resist the scorching heat. Initiated in 2006 as the world’s first planned sustainable city, Masdar was touted as a model for a green mixed-urban landscape and global hub for the clean tech industry.

Reflective panels

situated over solar

panels in Masdar

However, a decade on only a fraction of the town has been built. Instead of its 45,000 planned homes, there are just 300 students living on the site. Held back by the recent world economic crisis, and a lack of businesses and people who want to live there, its completion date was this year pushed back to 2030. But not all smart cities are like Masdar.

The collaboration of investment in networks is the next evolutionary step for smart cities

Asked how a successful smart city can be built from scratch, Neil Thompson, who leads the Construction Industry Council’s BIM2050 (Building Information Modelling) digital integration task group, says: “To have a master plan of the future, we are bounded by today’s technology. There is no point putting in fancy technology for the sake of doing so. We need to know what problems need to be solved. Knowing what the design outcomes are to make a city ‘smart’ is a first step.”

These might include the management of air quality, waste, water consumption, transportation and noise pollution. But you cannot manage what you cannot measure. This is true of energy management and generation. Everything must be connected.

Increasing collaboration

However, Richard Kirkman, Veolia’s technical director, does not believe there is a city that exists where a single unified monitoring system has been deployed. It is done in silos and by different organisations. “No one really controls everything at the same time. They have always devolved to be handled by separate organisations. The collaboration of investment in networks is the next evolutionary step for smart cities,” he says.

Yet this might happen in Singapore. Forced towards digital technology because of its geographical restrictions and dense population, in 2014 its government launched Smart Nation, a programme that will see an undetermined number of sensors and cameras deployed across the island state. Everything from the flushing of toilets to the precise movement of every locally registered vehicle will be monitored in real time.

Dassault Systèmes’ John Stokoe, head of strategic business development, who is building a 3D platform in the cloud to manage the environment, says: “Integrated and accurate data is the foundation of sustainability.”

Given some of the complexities involved, are smart cities still an aspiration rather than a reality? Andrew Comer, fellow of the Institution of Civil Engineers, says of the link between the technology and construction industry: “It’s taken the technology industry a long time to grasp the complexity of the real estate and construction industry, and is one of the reasons that the smart city is still an aspiration.

“This isn’t a big surprise. While cross-industry collaboration has promoted truly radical innovations, bridging the differing technical languages, regulations, procedural norms and complex value chains is difficult.

“Civil engineers plan, design and build the physical urban environment. To achieve our goal of creating evermore sustainable, attractive and efficient cities where people want to live, we need to better understand and embrace computer sciences, and work across wider domains to leverage the opportunities offered by technology.”

Overcoming barriers

One of the biggest barriers of all is not the technology itself; it is people. In June 2015, India’s prime minister Narendra Modi launched a national competition to find the best smart city proposal, with funding for phased development.

Mott MacDonald’s Anne Kerr, who worked on the proposed plans to regenerate the historic city of Jaipur in Rajasthan, says: “The greatest challenge was to hear, capture, and interpret the needs and aspirations of Jaipur’s citizens; an exercise requiring widespread and detailed community outreach and stakeholder communication.”

Driverless electric pod in Masdar to transport students from parking areas to the university campus

Schneider Electric’s director of smart city development Gordon Falconer points out another social issue. “One of the biggest barriers to realising the potential of smart cities is culture. We have the technology in abundance, but we need to do more to educate councils, industry, businesses and the wider community about the transformational potential of a truly smart city,” he says.

The United Arab Emirates has since applied the wisdom of lessons learnt from Masdar. This can be seen in Msheireb, the world’s largest regeneration project in Doha, Qatar. Tackling the issue of culture early in its plans, Msheireb’s architectural designs are built on the principles of preserving existing heritage sites.

According to Carl Castellino, director of facilities management at Msheireb Properties: “It prioritises culture for the Qataris. It makes sure it is a futuristic city while echoing the past.” He adds that apart from having the largest concentration of LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certified buildings in the world, “the patterns, the colours, the presentation and aesthetics were all considered with the traditional Qatari in mind”.

So perhaps the more successful smart cities will be those that have grown organically, with a top-down and bottom-up approach, putting people’s needs and aspirations first.

Within the next ten to fifteen years, we are likely to see a phased project approach to smart cities with the most basic of internet of things sensory technology and metering being installed to monitor water, energy and waste. The algorithms and tools to mine the data being collected will also evolve.

Learning from Masdar

Increasing collaboration