The fashion industry has arguably grown into one of the world’s most needlessly polluting, wasteful, energy-intensive and inefficient industries. Its supply chains are so fragmented, vast and distant that many retailers are unaware of how their fabrics are made, and who runs the factories that supply them. This dislocation is all the more concerning now that the life cycle of a garment is known to be far more environmentally damaging than previously assumed.

Microfibres shed from washing synthetic materials are estimated to account for 15 to 30 per cent of plastics found in the oceans, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Almost 65 per cent of all garments end up in landfill or are incinerated, releasing toxic chemicals as just 1 per cent are recycled, according to Wrap (Waste and Resources Action Programme). Global garment production, meanwhile, has doubled over the last 15 years, says the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, with supply vastly outstripping demand.

“The fashion supply chain, in all its discombobulated glory, is a problem in itself,” says Orsola de Castro, co-founder of the transparency index Fashion Revolution. “It is as inefficient as it is opaque. It is designed to hide rather than proclaim.”

Moving fashion production from home shores was the beginning of the end

This wasn’t always the case. Less than 30 years ago, most luxury fashion brands in Europe owned the factories that made their clothes. Garments for Armani, Dolce & Gabbana and Bottega Veneta were made in northern Italy. England’s textile industry thrived in Leicester, Manchester and Bradford. People could smell the leather tanneries, and see the factories and cotton mills. “The minute we moved the fashion industry from our shores, we lost touch,” Ms de Castro says.

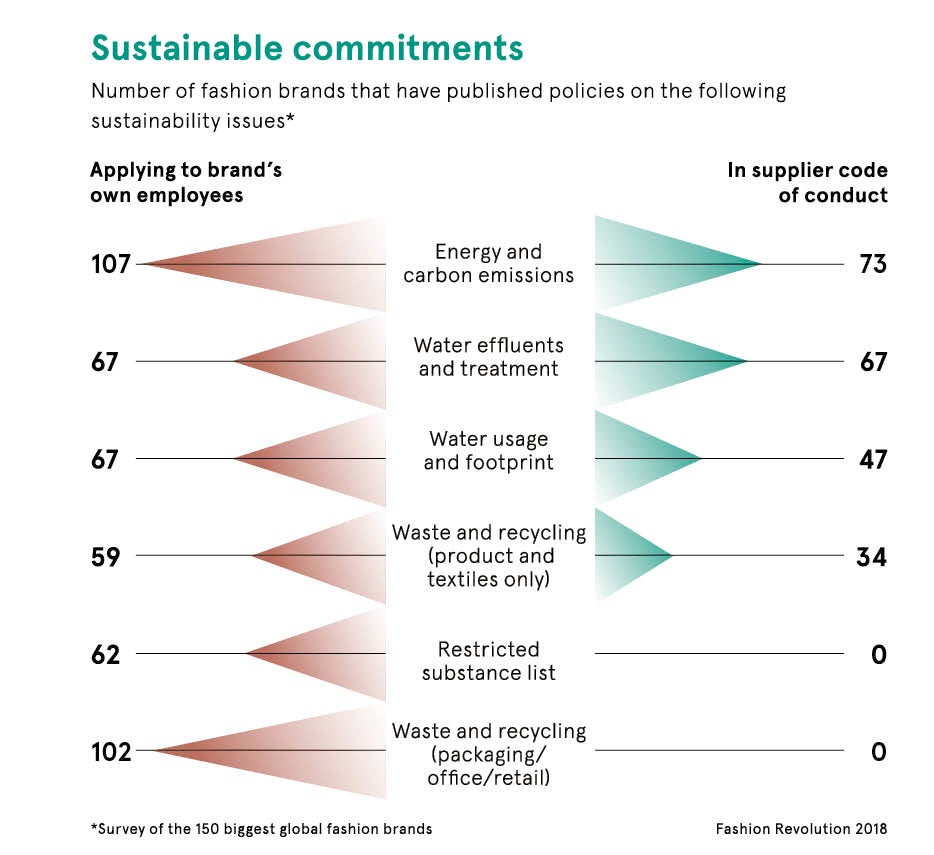

Corporate transparency is the first step towards raising universal standards across the industry and holding companies to account. It is impossible to police and prevent environmentally damaging processes if they are unknown, Fashion Revolution says. Its annual index ranks 150 fashion companies according to their public disclosure of sustainable policy and commitments, governance, traceability and remediation efforts. Encouragingly, this year industry-wide transparency has improved 5 per cent, but even so, only ten brands – adidas, Reebok, Puma, H&M, Esprit, Banana Republic, Gap, Old Navy, C&A and Marks & Spencer – scored more than 50 out of 100.

Overcoming entrenched business processes and corporate norms is a challenge even for companies committed to reform. “If you imagine a large design house, there is no relationship between the design studio and the sourcing team – that in itself is indicative,” says Ms de Castro.

Major fashion brands are moving towards sustainability

Several fashion companies are consulting with sustainable advisory firms, and investing research and development into alternative production methods and materials. In early-2018, adidas released a new sneaker line in collaboration with Parley for the Oceans that is made from fibres recycled from waste plastic. The luxury fashion conglomerate Kering has made commitments to cleaning its supply chain, by implementing the Natural Resources Defense Council-implemented Clean by Design programme across its brand suppliers.

Several fashion companies are consulting with sustainable advisory firms, and investing research and development into alternative production methods and materials

Sustainable ranges from high street brands, such as Zara’s #JoinLife, H&M’s Conscious and ASOS Africa, carry a slightly higher price point and take slightly longer to produce, but are traceable and use environmentally friendly fabrics and processes. Tellingly their designs also tend towards classic minimalism over current trends. These efforts represent a step in the right direction, Ms de Castro acknowledges, but she says such standards should be the norm across these multinationals.

For consumers concerned about their environmental impact, small and medium-sized fashion brands founded on sustainable business processes represent the best bet. Reformation and Everlane in the United States are entirely vertically integrated and made onshore, so waste is minimised and labour and environmental practices are above board. Others are nimble enough to provide closed-circle services, such as T-shirt company For Days which replaces stained or damaged T-shirts with recycled new ones.

Rolling ranges, produced onshore, could be the way forward

Jenny Houghton, founder of Fashion Enter, based in Haringey, London, provides support on running a sustainable business for young fashion brands. She maintains that retailers and factories “need to be joined at the hip and work as one”. Like many of the industry’s critics, Ms Houghton identifies its relentless season-driven focus as creating systemic inefficiencies, which are amplified if retailers buy in bulk from overseas. “Suppliers in China tend to want long production runs of 5,000, which require commitments of nine months ahead on production,” she says.

Rolling ranges produced onshore, she believes, are the way forward. “A good buyer will squeeze the life out of a best-selling garment – changing the colour or print, adapting it for a specialty section such as ‘petite’ or ‘maternity’. It is all about reaction to consumer demand,” she adds. This approach favours smaller runs of 800 to 1,200 units compared with an average of 3,000, which is far more sustainable from environmental and business perspectives. “The retailer is not overbuying a style and therefore not contributing to landfill or discounting,” says Ms Houghton.

Consumers need to take responsibility along with brands

The UK may have stringent labour regulations, but if enforcement is lacking malpractice thrives. Compliance tools, such as voluntary audit Fast Forward, forensically interrogate the legal, labour and ethical standards throughout a company’s supply chain. Launched in 2016 by auditing company Complyer and used by the likes of ASOS, it follows all company transactions and tracks payments to staff.

Other technologies help companies to make ethical procurement decisions. Blockchain services offered by London-based Provenance enable companies to trace and certify their supply chain. Cloud-based system Galaxius tracks supply chain activity from fabric orders to garment delivery and enables performance-related pay calculations that can result in garment workers earning up to £17 an hour.

The fashion industry is changing, but people also need to take responsibility for their consumption choices. The average piece of clothing in the UK is kept for 3.3 years before it’s discarded, according to Wrap. Sustainability campaigner Livia Firth invites consumers to consider whether they would wear an item at least 30 times before they commit to buying it. “We need to acknowledge that as consumers our wardrobes are part of the supply chain,” Ms de Castro concurs.

Moving fashion production from home shores was the beginning of the end

Major fashion brands are moving towards sustainability

Rolling ranges, produced onshore, could be the way forward