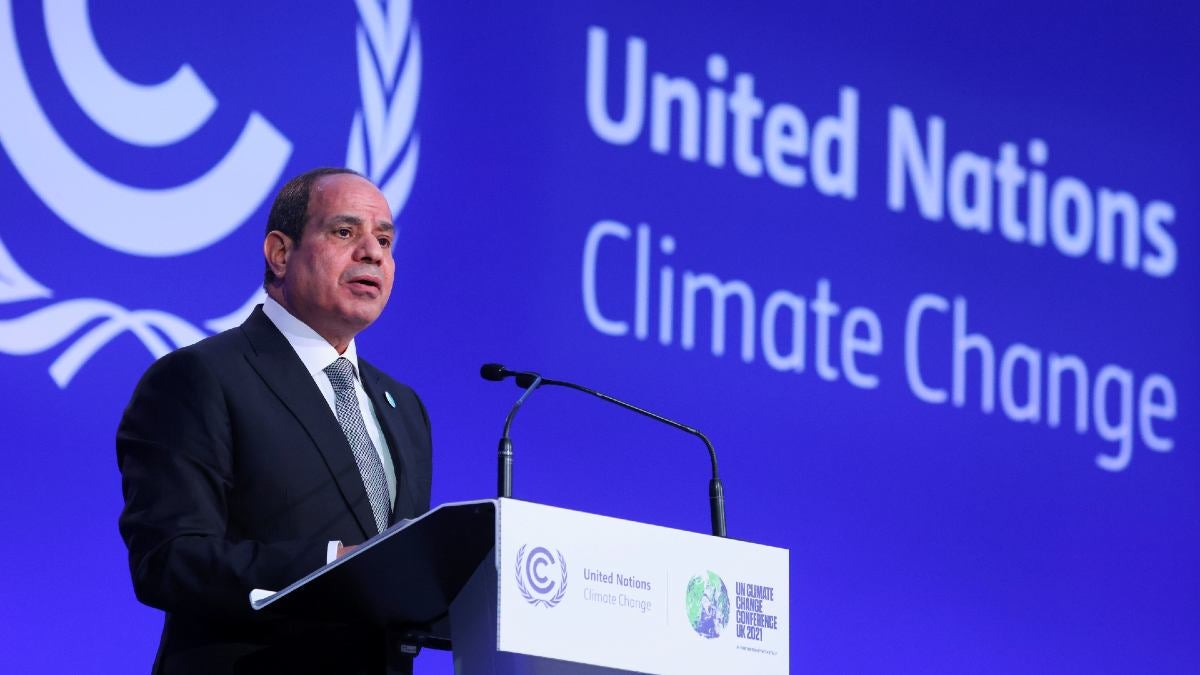

More than 90 heads of state, 55 corporate sponsors and 35,000 representatives are preparing to gather for the UN’s 27th conference on climate change, held between 6 and 18 November in the desert city of Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt.

The stakes may have never been higher. COP27 comes at the tail end of a year marked by unprecedented global pressures, not least a wave of climate-related disasters. Record summer heat in Europe, devastating wildfires in the US, and vast floods in Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sudan have been followed by a flurry of new reports showing just how close the planet is to “irreversible climate breakdown” and well over 2°C of warming.

Over 11 thematic days, and hundreds more formal and informal discussions, leaders will hash out how, and if, the world can avoid those doomy forecasts. But what exactly will be on the table at the latest round of talks? Here’s what you need to know.

A focus on the ‘how’

The outcomes of COP27 are trickier to predict than previous conferences, experts agree. “It was very clear what success was going to look like at COP26 in Glasgow because countries needed to deliver stronger targets,” says Gareth Redmond-King, international lead at the Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU). “It’s a bit harder with this one because it’s midway through several processes.”

But that does not mean we will not see progress. Rania Al Mashat, Egypt’s minister for international cooperation, said that the country wants its COP27 presidency to focus on “moving from pledges to implementation… the practical policies and practices, the processes that can actually push the pledges [into action], to bridge that gap.”

That will include technical discussions on how countries should measure their emissions, reviews of existing targets and the creation of a work programme for climate mitigation. According to the UN, this should “pave the way” for the first Global Stocktake of progress, planned for COP28 in 2023.

Climate finance

The issue of funding for efforts to cut emissions and protect against the effects of climate change, particularly in developing countries, will be top of the agenda again this year. Rich nations have repeatedly failed to deliver on finance pledges made at previous COPs.

“Wealthy countries promised over a decade ago that they would be delivering $100bn in climate finance to developing nations by 2020,” says Redmond-King. “That’s now three years overdue and we are still $17bn short.”

Last year, a commitment was made to finally hit that target by 2023, with a new deal to be negotiated to start in 2025. At COP27, there will likely be renewed pressure to significantly scale that up. According to some estimates, by 2030 developing countries alone could need $300bn annually just to adapt to climate change.

Lord Adair Turner chairs the Energy Transitions Commission and formerly headed up the UK’s Financial Services Authority. He points out that there is still ambiguity about what exactly should count towards the existing target. Negotiations will likely focus on nailing down the specifics, he says.

“There is a danger that otherwise the finance discussion is dominated by a set of arbitrary figures, rather than a systematic analysis of what’s really required. How much for [retiring] coal, how much for ending deforestation, how much to drive investment in renewable power systems?”

Debate also continues over what kind of financing should count. At present, the total covers both ‘no strings attached’ grants and investments for which financers want returns. According to an Oxfam analysis, at present the majority of financing is in the form of loans, sinking the world’s poorest countries further into debt.

Reparations for loss and damage

A subset of climate finance, loss and damage was not discussed at COP26 despite long-standing demands from activists and climate-vulnerable nations. They have called for lower-emitting countries to be paid compensation for harms experienced by their citizens as a result of climate change, such as destruction from flooding or hurricanes.

Redmond-King believes it “will be a litmus test issue” at COP27. “If parties were to go away from Egypt without meaningful progress towards loss and damage then I think it will damage trust and confidence in the [COP] process.”

Denmark recently became the first country to offer specific loss and damage compensation. But Turner thinks the concept is too “contentious” for the majority of countries to accept – and does not see that changing this year. “There has never been any formal acceptance by the developed world that they have any intention of paying for loss and damage,” he says.

Africa takes centre stage

The Egyptian government has proclaimed this a “COP for Africa”, promising to foreground climate issues affecting the world’s poorest continent. Six of the V20 group of climate-vulnerable nations are located there and many others are already facing huge challenges, from drought to coastal flooding.

Meanwhile, a significant proportion of global fossil fuel reserves lie in Africa, many of which are untapped. If developed, these resources could help lift millions out of poverty on a continent where just half the population has access to electricity.

Should Africa develop fossil fuels? Or should it skip a generation to renewable energy?

That could spark “big debates”, says Turner. “Should Africa develop fossil fuels? Does it have to carbonise its economy before it decarbonises? Or can it – and should it – skip a generation straight through to renewable electricity?”

He expects to see “a tension between financial institutions and governments in the rich developed world saying that we shouldn’t be developing new oil and gas and African countries saying, ‘Well, you developed your oil and gas, why shouldn’t we develop it for a period and get the economic benefit?’”

The impact of global affairs

COP has always been inseparable from geopolitics and this year temperatures will run higher than most. In particular, Russia’s war in Ukraine has prompted many countries to prioritise energy security over emissions reductions, even leading some to reopen coal plants. Many fear this could be a distraction from climate negotiations, however it could also help to drive them forward.

“There are lots of global crises that have the attention of leaders,” says Redmond-King. “But it’s been very clear that all of these crises are interconnected with the climate crisis. The conversation about solutions overlaps heavily with climate solutions too.

“We see it most starkly with Europe’s race to end reliance on Russian gas. It’s very much speeding up the clean transition. Their plans probably now outstrip their targets under the Paris Agreement.”

He points to a “wider momentum” independent of the COP negotiations: the US’s $500bn commitment to green energy under the Inflation Reduction Act and China’s enormous investment in offshore wind. “The international meetings themselves in some ways are not going as far as real action on the ground being driven by governments, investors and markets.”

The UK’s role shrinks

The UK’s COP26 presidency was widely seen as successful and raised the country’s profile as a climate leader. It was also one of just 24 nations to submit an updated emissions reduction pledge (called a Nationally Determined Contribution, or NDC) ahead of COP27. However, there are fears the political turmoil of recent months could undermine that image and distract from the negotiations.

COP26 President Alok Sharma criticised Prime Minister Rishi Sunak for failing to commit to attending this year’s conference (Sunak later confirmed he will go with just five days’ notice). Meanwhile, King Charles, well known for his environmentalism, will stay at home.

That, along with recent see-sawing on domestic environmental issues such as fracking, concerns British energy leaders. “We’re just seeing more and more delays and what worries me from a UK perspective is that other countries are getting things moving. I think we risk becoming a follower when we could be a leader,” says Steve Scrimshaw, vice-president for UK & Ireland at Siemens Energy.

“When I left COP26 it felt like all the pieces and parts were on the table and they just needed that little push to get them over the line. And I’m hoping that COP27 actually moves to deliver it.”

More than 90 heads of state, 55 corporate sponsors and 35,000 representatives are preparing to gather for the UN’s 27th conference on climate change, held between 6 and 18 November in the desert city of Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt.

The stakes may have never been higher. COP27 comes at the tail end of a year marked by unprecedented global pressures, not least a wave of climate-related disasters. Record summer heat in Europe, devastating wildfires in the US, and vast floods in Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sudan have been followed by a flurry of new reports showing just how close the planet is to “irreversible climate breakdown” and well over 2°C of warming.

Over 11 thematic days, and hundreds more formal and informal discussions, leaders will hash out how, and if, the world can avoid those doomy forecasts. But what exactly will be on the table at the latest round of talks? Here’s what you need to know.