It is clear that the number of responsible and sustainable investment funds is only going in one direction: up. According to the Investment Association, UK retail investors poured more than £7 billion into these funds during the first ten months of 2020.

But legislation regarding environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing is less straightforward. In the void, multiple definitions, acronyms and industry body initiatives have sprung up, all working to define and monitor the booming number of ESG funds.

Without doubt, legislation is necessary, as Amy Clarke, chief impact officer at Tribe Impact Capital, warns: “In the absence of regulation, there is a growing sense that we may be approaching another product mis-selling scandal.”

Here are the most important moves from industry bodies and regulators to standardise the ESG industry.

1. EU Taxonomy

The European Union Taxonomy for sustainable finance is the most substantive regulation that has challenged the financial industry on green issues.

From March 2021, asset managers will be required to start upping their reporting game, stating to what extent their green funds, or any fund that claims to have environmental objectives, are aligned with the EU Taxonomy framework.

Helena Viñes Fiestas, global head of stewardship and policy at BNP Paribas Asset Management, explains there are 32 indicators asset managers have to report on, covering everything from due diligence and remuneration to adverse impacts on society and the environment.

“This concept of ‘double materiality’ is where you not only have to take investment risk into account, but also the risk to society and the environment, and it will cover everyone from asset managers and banks to data providers and credit rating agencies,” she says.

There is no minimum requirement of alignment that a fund has to hit to be marketed as green, unless the asset manager wants to adopt the new “Ecolabel” for retail investors, but even then the threshold has not yet been set. Instead, the European Commission points to “minimum safeguards” being the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises and United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

Due to Brexit, the Taxonomy will only apply to UK asset managers selling their products to European investors.

2. MiFID II

The Markets in Financial Instruments Directive is being updated by the EU to require product providers to ensure investors’ wishes around ESG are considered when recommending a product to invest in.

“It will be compulsory to ask clients’ ESG preference and to match that,” says Clarke at Tribe Impact Capital. “The only obligation attached to the Taxonomy is the reporting side of things. The MiFID amendment is a smart way to get around the fact that the Taxonomy has not set a minimum requirement of alignment.”

In other words, the update to MiFID will ensure end-investors do not become victims of greenwashing and unfounded green claims.

3. TCFD

The Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures was set up by the Financial Stability Board to provide a way of reporting common climate-related financial risk disclosures that could be used by companies to enlighten their investors.

“A lot of the big institutional managers have to get their heads around what sustainability really means,” says Clarke. “The work of the TCFD has pushed them to look at the level of climate risk embedded in their portfolios and has put pressure on the industry in general.”

But the UK is not a member of the TCFD. However, this year the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) proposed a new rule which would require UK-listed companies to comply with the TCFD recommendations and, if not, explain why.

Groups including the Investment Association claim the rule doesn’t go far enough and have called on the government to make TCFD disclosure mandatory for all listed firms, not just those with a premium listing. The FCA completed consultation in October and will finalise its position this winter.

However, the TCFD is not the only body working to harmonise how the financial industry goes about disclosing climate-related information. The International Organization of Securities Commissions, the global regulatory body, is working to translate all reporting frameworks, including that of the TCFD, into one model which can be used consistently across the board.

4. Pension Schemes Bill

At the moment, UK pensions have a lot of free reign, evidenced by movements like the Make My Money Matter campaign which, in the absence of other requirements, encourages pension providers to commit to all their default pension funds being carbon net zero by 2050.

But the Pension Schemes Bill, making its way through the UK parliament, could change things fast. It would require large pension funds to disclose climate-related risks to assets in their portfolios by 2022, in line with TCFD recommendations.

“The bill will be very welcome; whether it sets the bar high enough remains to be seen,” says Clarke. “ESG is a good starting point, but it’s really an entry-level activity. The Dutch and Scandinavians are well ahead of us on this.”

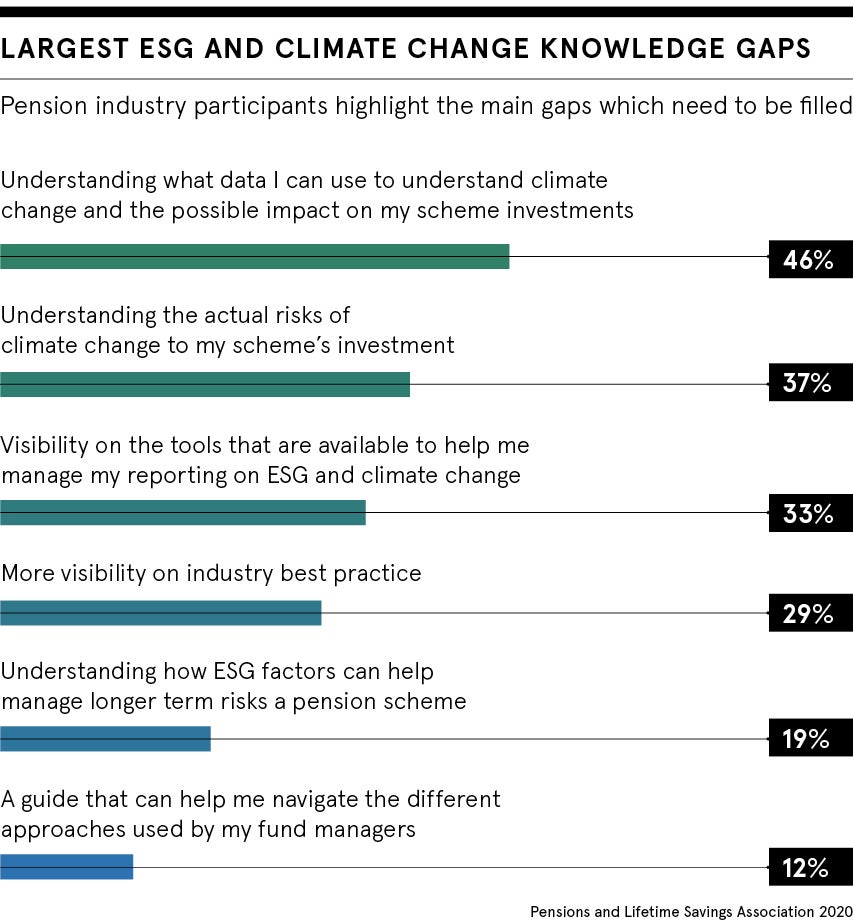

A recent report from the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association said pension providers should adopt TCFD guidelines around reporting and provide more training for pension trustees on ESG issues.

5. Responsible Investment Bill

Following the lead of Scandinavian countries, charity ShareAction and the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Sustainable Finance have proposed a Responsible Investment Bill, which would increase directors’ accountability for their investment decisions, allowing beneficiaries of investment schemes to seek judicial redress.

Going much further than the Pension Schemes Bill, it would require default and green pension funds to align with the Paris Agreement, and for this to be enforced by the FCA and the Pensions Regulator. It would also force pension providers to ask beneficiaries about their ESG views.

“This proposal is absolutely grounded in pension funds delivering the strategies which are in the best interests of their beneficiaries, trying to break out beyond the straitjacket of profit maximisation,” says Catherine Howarth, chief executive of ShareAction.

“It’s not trying to prescribe how pension schemes invest, rather it takes them through a process to check they’ve thought in a more holistic way about strategies that will deliver the best long-term outcomes to the people they owe duties.”

6. UK Stewardship Code

A decade after the Financial Reporting Council introduced the UK Stewardship Code, for the first time it is now necessary for signatories to integrate ESG considerations into their decision-making. The new code has also moved away from “comply and explain” to “apply and explain”, minimising the opportunity for greenwashing.

As the code states, as of 2020 signatories must “systematically integrate stewardship and investment, including material environmental, social and governance issues, and climate change, to fulfil their responsibilities”.

7. B Corporations

Not all the positive reform and effort is on the investors’ side. There are growing numbers of so-called B Corporation companies, totalling more than 3,500 around the world and 250 in the UK.

These companies are like for-profit versions of social enterprise, placing equal emphasis on people, planet and profit. A recent example is Bookshop.org, which raises sales for independent bookshops. Some are listed and certified B Corps include subsidiaries of very large companies such as Unilever and P&G.

“B Corps emphasise a growing movement from shareholder to stakeholder capitalism and in the process strengthen the link between business and society,” says Tribe Impact Capital’s Clarke.

It is clear that the number of responsible and sustainable investment funds is only going in one direction: up. According to the Investment Association, UK retail investors poured more than £7 billion into these funds during the first ten months of 2020.

But legislation regarding environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing is less straightforward. In the void, multiple definitions, acronyms and industry body initiatives have sprung up, all working to define and monitor the booming number of ESG funds.

Without doubt, legislation is necessary, as Amy Clarke, chief impact officer at Tribe Impact Capital, warns: “In the absence of regulation, there is a growing sense that we may be approaching another product mis-selling scandal.”