Electric vehicles, or EVs, are often billed as game-changers, a way of meeting our need to be mobile without the emissions that come from traditional internal combustion engines. Yet their take-up remains relatively slow, with consumers beset by so-called range anxiety and worries about a recharging infrastructure still in its infancy. Meanwhile, sceptics even question the veracity of EVs’ green credentials.

While they may have zero tailpipe emissions, every Nissan Leaf and BMW i3 does come with embodied emissions, much of it wound up in the extraction and transportation of the rare-earth metals at the core of EV batteries. Mining these minerals is often mired in other environmental and human rights controversies, too.

As Amnesty International’s secretary general Kumi Naidoo says: “Finding effective solutions to the climate crisis is an absolute imperative and electric cars have an important role to play in this. But without radical changes, the batteries which power green vehicles will continue to be tainted by human rights abuses.”

EV sceptics also point to the fossil fuels burnt to create the electricity needed to run them, but this is where electric vehicles start to fight back, thanks to the increasing decarbonisation of energy supplies.

The drive for decarbonised electricity

According to Helen Perry, Nissan Europe’s head of EVs, once you compare the combined embodied and operating emissions of a conventional car and an EV, the latter is far more environmentally friendly.

“The battery and manufacturing phase of the vehicle’s life contributes a significant proportion of the overall result. But, of course, once in use an EV has zero tailpipe emissions,” she says. “The shift from fossil-fuel power stations to renewable and other energy sources means the contribution to overall life-cycle emissions from charging the vehicle continues to rapidly decrease.”

There are other ways that electric vehicles are cutting their carbon footprint. Light-weighting is a process that makes products lighter by reducing the amount of materials used to make them or by transitioning to lighter alternatives.

There are also moves to cut the carbon associated with transporting components from all over the world by sourcing and manufacturing locally. Tesla is leading the way with its Gigafactory, a massive EV and lithium-ion battery assembly plant in Nevada, with a second currently being built in Germany.

There is no silver bullet to tackling emissions, but EVs will be a core part of what’s needed and the energy grid is ready to power them

Companies are also starting to do clever things with batteries. Volvo is investigating ways in which it can integrate battery components into the vehicle body to reduce weight, while Renault is using electro-magnets, which don’t need rare-earth metals, in their engines.

And with so much of the cost of an EV tied up in the battery, research is also ongoing into fuel cells, which produce electricity through a reaction between oxygen and hydrogen, and could eventually replace both conventional engines and batteries.

Electric vehicles charging ahead

So what’s holding back faster growth of the EV market? “It’s no secret that despite the attractive proposition electric vehicles have always posed to consumers looking for a greener, more ethical alternative to petrol and diesel, actually buying one hasn’t always been an easy choice to make,” says Richard Seale, lead automotive designer at design agency Seymourpowell.

While Seale points to the likes of Tesla, Porsche and BMW delivering “blistering performance” in terms of design, there are still barriers to purchasing an EV, he says. “They are still not cheap, there is not an extensive second-hand market and range anxiety still plays a part. But the big one for me is the charging infrastructure,” he adds.

Perry believes there are numerous incentives that can be introduced to help increase the take-up, such as discounted charging, road tax exemption and plug-in car grant. She agrees charging remains a deciding factor for many, but also sees changes ahead.

“With more brands and models entering the EV market, more people are likely to consider buying one. Over time, this will benefit everyone by stimulating growth in the EV and charging infrastructure market as a whole and, as volumes rise, will help to bring prices down,” she says.

Weighing the commercial considerations

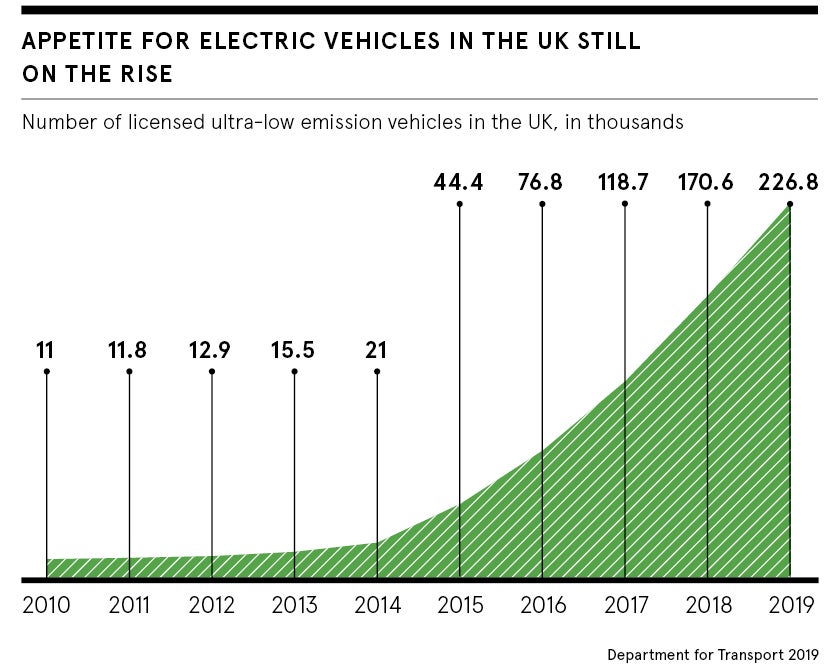

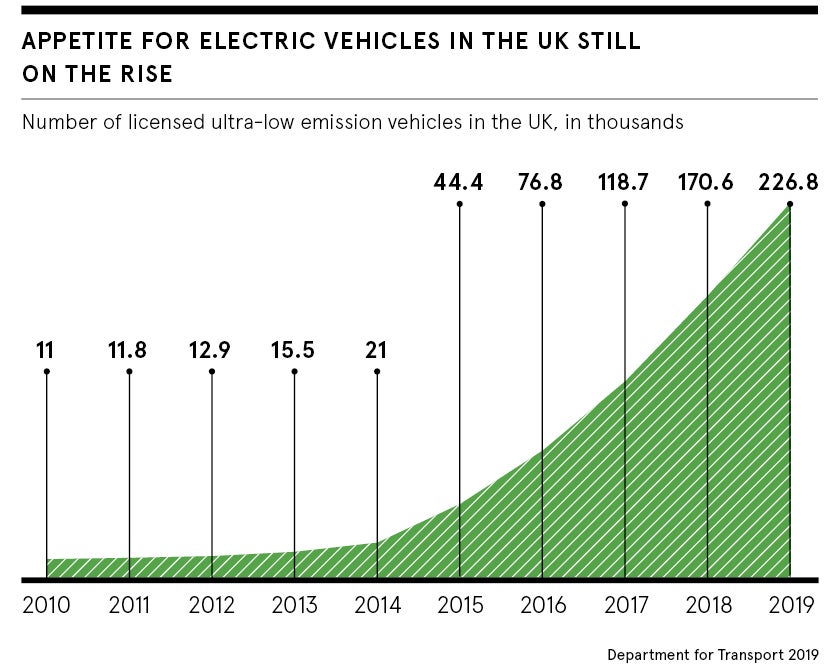

Although the impact of electric vehicles on consumers takes centre stage, commercial vehicles will also be affected by policies such as the UK government’s Road to Zero strategy, which aims for at least half of all new vehicles to be ultra-low emission by 2030, as well as implementation of clean air zones in major cities.

Hitachi Capital Vehicle Solutions is part of Optimise Prime, the world’s largest commercial EV project, which is looking at how to help UK companies overcome barriers to electrifying their fleet.

“The cost of electric or alternate-fuelled commercial vehicles and the infrastructure to support the transition will undoubtedly be a major investment for fleets,” says the company’s managing director Jon Lawes. “However, this cost will almost always be exceeded by the running of a diesel fleet.”

Hitachi’s research shows that with more than 65.7 billion miles commercial vehicles travelled each year in the UK, the fuel savings would total approximately £13.7 billion if all fleets transitioned to alternative fuels. “The key is to help businesses recognise that it isn’t just beneficial for the environment, but cost effective as well,” says Lawes.

But can the UK’s electricity system meet the demand for a new generation of electric vehicles? Nicola Shaw, executive director at the National Grid, believes so. “Most journeys we make are relatively short – the average car does around 30 miles a day – but when we buy a car, we expect it to make some longer journeys too,” she says. “To help people feel confident to choose an EV and to ease worries about running out of charge, we need the right charging infrastructure.

“That’s why National Grid is asking the government to commit to a nationwide ultra-rapid charging network, to put over 99 per cent of drivers within 50 miles of a hub that will charge an EV in the time it takes to pick up a cup of coffee.

What does the future hold for EVs?

“There is no silver bullet to tackling emissions, but EVs will be a core part of what’s needed and the energy grid is ready to power them.”

Seymourpowell’s Seale also believes there is a lot to be learnt from China, particularly in the way it incentivises electric vehicles, while actively disincentivising petrol and diesel. China wants alternatively fuelled vehicles to hit 20 per cent of all new vehicle sales by 2025. To achieve this it is putting considerable barriers in the way of conventional car owners, such as forcing them to enter a lottery to gain a registration for their vehicle; there are no such hurdles for EV ownership.

“Choosing an EV allows you to be part of a growing infrastructure of clean energy, an infrastructure that is only getting better,” he says. “Choosing an EV allows a consumer to become part of the solution.”

The drive for decarbonised electricity

Electric vehicles charging ahead