Shipping is the last bastion of dangerous low-grade, high-sulphur fuels. It accounts for just 2 per cent of global carbon emissions, but produces 13 per cent of the world’s sulphur emissions and 15 per cent of nitrogen oxides.

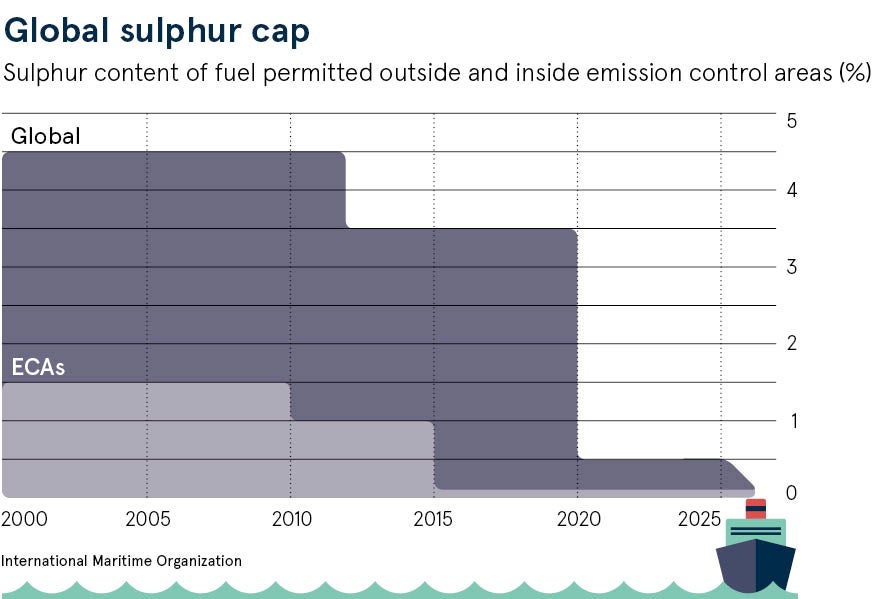

Banned from every other industry, these fuels have remained in the maritime economy partly because shipping routes tend to be far from human habitation. On January 1, 2020, however, this exemption will be lifted, when landmark regulation introduced by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) will slash the permitted sulphur content in ships’ fuel from 3.5 to 0.5 per cent.

Cleaner fuels could almost halve the number of premature deaths and diseases caused by the industry

At the heart of the IMO’s decision is a desire to protect health. Shipping’s dirty, cheap fuels cause around 400,000 premature deaths a year through heart and lung illnesses, and asthma in 14 million children, according to research published in Nature. Cleaner fuels could almost halve the number of premature deaths and diseases caused by the industry, with people living close to ports and major shipping routes seeing the greatest health benefits.

Banning high-sulphur fuels could push up oil prices

However, uncertainty over the economic impact and probable rise in crude oil prices, which is expected to be passed on to consumers, concern some analysts. Shipping accounts for 10 per cent of the world’s demand for oil in the transport sector, with one container vessel consuming 80 tonnes of high-sulphur fuel a day, the equivalent of 46 million cars running on diesel, according to HSBC.

Cost estimates range from an alarmist $1 trillion to the global economy, with crude prices rising $7 a barrel in 2020, predicted by S&P Global Platts, to the phlegmatic from Maersk, which runs the world’s biggest container shipping line, estimating an annual total cost to the container shipping industry of between $5 billion and $30 billion.

Paddy Rodgers, chief executive of Euronav, a global oil tanker operator, is sceptical about predicted shocks. “The cost of transport is always connected to the price of oil and nothing will change, so there is no big seismic shock coming to the industry as a result of this,” he says. “It is within the normal volatility range of the price of oil.”

Low-sulphur alternatives for shipping fuels

Some waters, including the Baltic Sea, North Sea, Mediterranean, Caribbean and most of the US and Canadian coasts, which have signed up as sulphur emission control areas (SECA), are already subject to a far more stringent sulphur cap at 0.1 per cent. And most of the global oil majors, including Shell and Exxon, say they will produce enough compliant fuel to meet demand, while HSBC predicts an initial compliance rate of 80 per cent.

What these compliant fuels will be is unclear. Low-sulphur oil is the most obvious option, but lingering concerns remain over oil producers’ capacity. Liquified natural gas has its proponents as it emits about 25 per cent less carbon dioxide than conventional shipping fuels, contains virtually no sulphur, 85 per cent less nitrogen oxide and 99 per cent less particulates. But its higher methane emissions, closely linked to climate change, are a problem. Beyond fossil fuels, battery technology and hydrogen power are climate-change safe, but as yet untested.

One under-scrutinised aspect of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) is the option to use alternative abatement technologies. These “scrubbers” as they are called remove exhaust sulphur emissions from ships’ smoke stacks, enabling a continuing market for high-sulphur oil. It is a booming sector, despite the high capital cost of installation at as much as $5 million a ship, with the number of companies manufacturing scrubbers up from three to thirty since the 2016 updated MARPOL regulations.

But Mr Rodgers cautions: “Unlike any other industry that uses sulphur-rich fuel, the scrubbing system will not capture and neutralise the sulphur, it will simply pump the sulphur out of the ship and have it bind to seawater which will be returned to the ocean.” Whether this is environmentally safe is open to question because of the limited amount of scientific research, leaving aside the carbon-dioxide emissions.

New tricks needed to police high-sulphur fuel use

What is more, the use of scrubbers creates a two-track system within the industry and attendant worries over enforcement, which is already an issue in the northern European SECA region.

Researchers at Sweden’s Chalmers University of Technology found the lowest levels of compliance in the western part of the English Channel, near the SECA border, where 13 per cent of vessels were in violation of the sulphur regulations in September 2016.

“In general, the vessels carry both low-sulphur fuel oil and the less expensive high-sulphur oil on board,” says Chalmers University’s Johan Mellqvist, professor of optical remote sensing. “If they switch fuel well in advance of their passing of the measuring stations, they won’t be caught out.”

For this reason the university developed an aerial system for monitoring marine vessels’ emissions, which advises port authorities which ships they should select for on-board fuel inspections.

Sulphur emissions are only one part of the vast environmental challenge facing the marine economy. Ocean pollution, including plastics, rising carbon levels causing acidification and widespread death of marine life, ocean warming and rising sea levels present a many-headed hydra of problems.

In April, the IMO agreed to at least halve the industry’s carbon emissions from 2008 levels by 2050 and at the Global Maritime Forum, in early-October, 34 chief executives demanded faster climate action.

Banning high-sulphur fuels could push up oil prices

Low-sulphur alternatives for shipping fuels