For the insurance sector’s major players, the biggest immediate challenge presented by climate change has been an increasing frequency of extreme weather events, ratcheting up underwriting costs.

According to the Association of British Insurers (ABI), the extremely cold weather that hit the UK in early-2018, for example, resulted in insurers paying a record £194 million for burst pipes in just a three-month period.

Thomas Parmentier, European insurance analyst at UBS Global Wealth Management, says the value of insured assets has increased dramatically over the last decade, chiefly due to the “increase in property values and consequently claims for the industry”.

But insurance investment management is increasingly attracting scrutiny and arguably highlighting a far more systemic and complex crisis. The value of many of the assets insurers hold could easily be imperilled by an accelerating transition towards a low-carbon economy that shuns fossil fuels and assets contributing to greenhouse gas emissions.

The increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events could trigger non-linear and irreversible financial losses

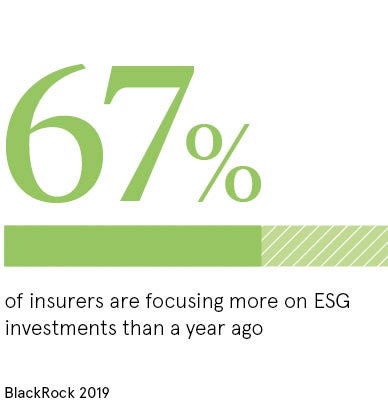

The ABI estimates that UK insurers alone hold in excess of £1.8 trillion in invested assets. A May 2018 report by the Department for International Trade notes, however, that only around 1.2 per cent of all assets under management in the UK were invested sustainably, compliant with good environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles, which means the shock of decarbonisation could be disastrous for those who fail to adapt.

A stark warning for insurance investment management

Last July Moody’s, the agency that assigns credit ratings to corporations which can determine their ease of access to funding, issued a stark warning to insurers, signalling failure to decarbonise could cause severe damage and, in some cases, mean insurers fail to meet financial obligations.

“Climate change in particular gives rise to greater uncertainty for insurers, both with respect to expectations for frequency and severity of natural catastrophes, and exposure to carbon-transition risk through their investment portfolios and the possibility of stranded assets,” according to Brandan Holmes, senior credit officer at Moody’s.

In the foreword to an extensive analysis on climate-change risk, published by the Bank of International Settlements in January, François Villeroy de Galhau, governor of the Bank of France, issues a similarly austere warning.

“The increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events could trigger non-linear and irreversible financial losses,” he says. “In turn, the immediate and system-wide transition required to fight climate change could have far-reaching effects potentially affecting every single agent in the economy and every single asset price.”

Leading the sustainability charge

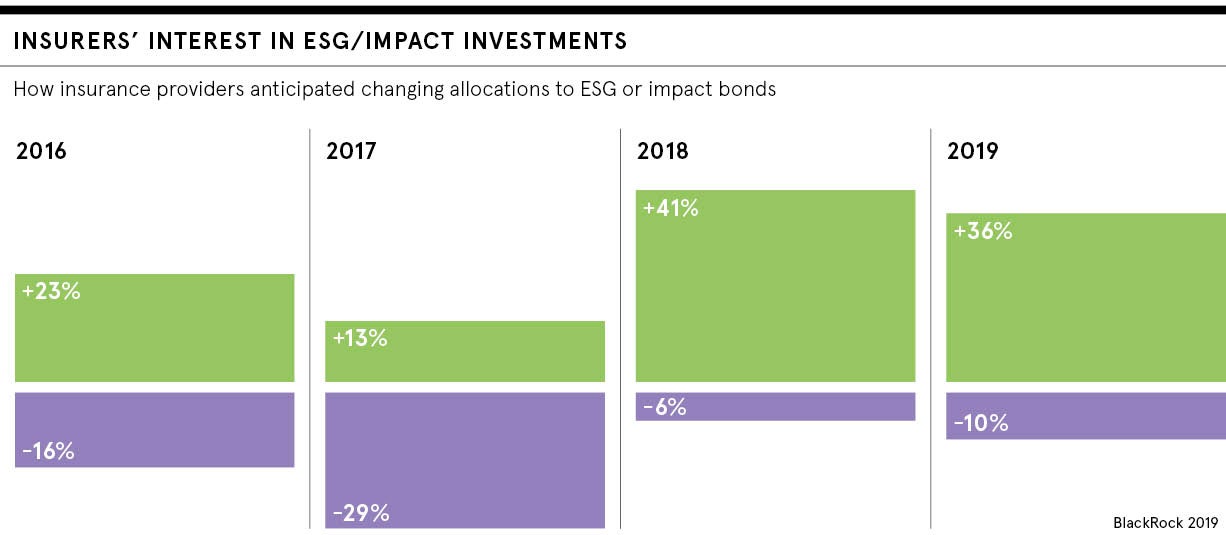

Though progress towards adapting to a new ESG-centric world has in many cases been sluggish, there are some insurance companies that are paving the way.

In November 2019, Paris-based multinational insurance firm AXA committed to aligning its investments with the United Nations-backed 2015 Paris Agreement and pledged to commit to a 1.5C warming potential by 2050. The warming potential is defined as the impact AXA’s investments may have on climate, expressed in temperature.

AXA in 2015 became the first of the major investors to divest from the coal industry and it has since committed to a complete coal exit by 2030 in Europe and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, and by 2040 for the rest of the world.

A significant development forcing insurance investment management to become greener is that the world’s largest asset managers’ efforts to decarbonise are gathering pace, setting a standard.

Climate change bad for more than business

In January, Larry Fink, chief executive of bellwether BlackRock, which has approximately $7 trillion of assets under management, wrote to business leaders stating that they must stamp out unsustainable business practices or risk serious economic repercussions, in addition to irreparable damage to the planet.

Fink warned his company would “be increasingly disposed” to cast critical proxy votes if organisations were not committing to greater sustainability. In a separate letter to BlackRock’s clients, he vowed that by the middle of this year the firm would divest stakes in companies in BlackRock’s actively managed portfolios which derive more than 25 per cent of their revenues from thermal coal production.

Martha McPherson, head of green economy and sustainable growth at University College London’s Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, says insurance companies have an obligation to adjust, even if some financial services firms are lagging in their commitments.

“Nobody needs reminding that the climate crisis is urgent, but the responses of some players in the UK’s financial sector have been glacial. With the UK hosting COP26 in November, now is the time to make a genuine, cross-sector commitment to tackle climate change,” she says.

As for insurance investment management, McPherson says companies are already aware of their role to price and manage risks, and offer security to both their policyholders and society more broadly. She concludes: “It is inevitable that insurers will need, and want, to play an increasing role in championing a low-carbon economy.”

A stark warning for insurance investment management