From Bristol to Leeds, Swansea to Manchester and Nottingham to Edinburgh, local authorities are facing one of their biggest challenges in decades; how to finance projects to solve climate change at a local level as they transition to a low-carbon future for their communities.

Many have pledged to shift to 100 per cent clean energy by 2050 to reduce air pollution and cut related deaths, while ushering in new energy-efficient measures across homes, businesses, transport and infrastructure.

However, central government funding for such innovative initiatives can’t ever finance the number of projects on the table, leading to cash-strapped councils seeking development capital from the private sector.

Such green finance initiatives are now increasingly recognised as a lucrative choice by private investors, but there is still a lack of confidence, often due to issues over market clarity, alongside inconsistent government policy and ever-changing regulation.

As director of UK100, Polly Billington heads a network of more than 100 local authorities committed to the 2050 pledge. Her organisation’s members collectively campaign for greater central government assistance for local clean energy while sharing best practice.

She says: “Local authorities’ budgets are tight, but their commitment to acting on climate is strong. They want to see that investment in rebuilding the economy is aligned with meeting our net-zero target as a country and are keen to develop partnerships with the private sector to make it happen. But they struggle with capacity and know-how.”

Local authorities’ budgets are tight, but their commitment to acting on climate is strong

To combat this, UK100 is backing the idea of a net-zero development bank to work with local projects to gain private finance. Billington adds: “Without this kind of savvy deployment of taxpayers’ money to give the private sector confidence, we could miss our climate targets and the huge opportunity to rebuild our country in a way that leads the world in climate action and benefits the people who live in our communities.”

Local authorities lead in energy efficiency

From county council to city council and among combined authorities, the collective will, if not the funding, is there to make clean energy a reality.

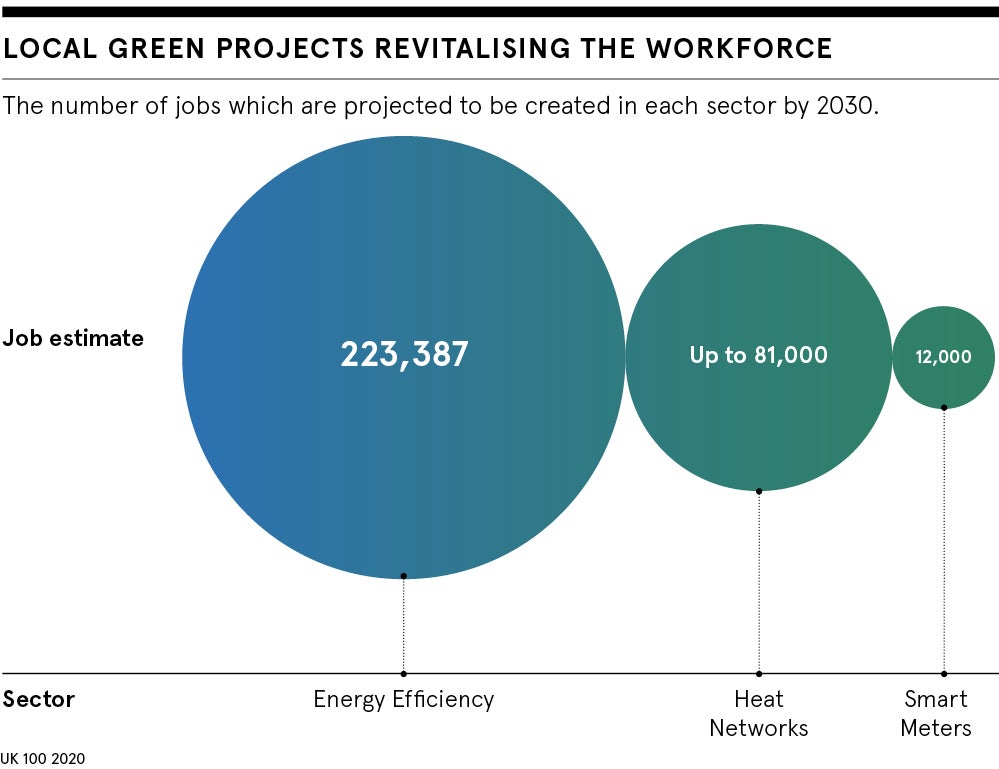

In its latest report, Accelerating the Rate of Investment in Local Energy Projects, UK100 says there is potential to unlock more than £100 billion of investment in local energy systems by 2030 through partnership approaches, but this requires £5 billion of initial development funding.

Projects include battery storage, an increase in renewable fuels, electric vehicles (EVs), and heat-led projects in homes and workplaces.

In Bristol, the first UK city to declare a climate emergency, a number of pilots are underway through its City Leap plan, which aims to combine significant private investment with innovative projects and community-led initiatives.

Mayor of Bristol Marvin Rees says: “In Bristol’s One City Climate Strategy we have mapped out the investment opportunities that will help create carbon-neutral energy and transport systems. Cities like Bristol are a catalyst to help facilitate investment by the private sector.

“We have developed our pioneering City Leap initiative to create an energy partnership which will attract over £1 billion in investment to help create a carbon-neutral Bristol by 2030.

“In recent years we have invested around £60 million in sustainable projects, including the development of our own wind turbines, the introduction of a low-carbon heat network, establishing an EV charging infrastructure and energy efficiency upgrades to more than 10,000 social homes.”

At Cheshire Energy Hub, £700,000 of government funding has delivered E-Port, a low-carbon smart energy system in the Ellesmere Port area, with private partners adding an additional £230,000 to meet total costs. Those behind the project say the blueprint could generate investment of £100 million in the region by 2025.

Ged Barlow, Cheshire Energy Hub chair, explains: “UK industry has reached a critical phase in its journey to net zero. In the North West we are beginning to see early signs of initiatives such as public-private co-investment in low-carbon infrastructure, public sector underwriting of industry’s low-carbon investment, simpler and more supportive planning regimes to support low-carbon technology, and a more holistic approach from industry and local government.

“They are working in partnership to attract low-carbon investment from national government and heavyweight institutional energy infrastructure investors.”

Harnessing the private sector for a green recovery

In Leeds, city council leader councillor Judith Blake says private investment will be essential, especially when it comes to decarbonising the city’s housing and transport.

“Local authorities like Leeds can be very effective at making the case for, and helping to facilitate, change-making private investment, but only if markets are receptive and there is a case to be made,” she says.

Interest does appear to be growing. Earlier this month, chancellor Rishi Sunak announced plans to issue the government’s first Sovereign Green Bond in 2021, subject to market conditions, and Labour has called for greater green investment to create hundreds of thousands of new jobs.

Banks are on board too, with Barclays setting a target of providing £100 billion of green financing by 2030.

Siemens Great Britain and Ireland is a private company invested in the project. Writing in the UK100 report, its chief executive Carl Ennis says: “There is an urgent need to scale up local energy investment across the UK if we are to have any chance of meeting net zero by 2050. This requires a national effort with government, business and the public all playing their part.”

Councillor Sally Longford, deputy leader of Nottingham City Council, which has the ambition to be the first carbon-neutral city in the UK by 2028, concurs. “Green investment is critical to facilitating this shift, enabling risk to be shared across the private and public sectors, but crucially enabling innovative technologies and solutions to be deployed, stimulating new green jobs and the low-carbon economy,” she concludes.

From Bristol to Leeds, Swansea to Manchester and Nottingham to Edinburgh, local authorities are facing one of their biggest challenges in decades; how to finance projects to solve climate change at a local level as they transition to a low-carbon future for their communities.

Many have pledged to shift to 100 per cent clean energy by 2050 to reduce air pollution and cut related deaths, while ushering in new energy-efficient measures across homes, businesses, transport and infrastructure.

However, central government funding for such innovative initiatives can't ever finance the number of projects on the table, leading to cash-strapped councils seeking development capital from the private sector.