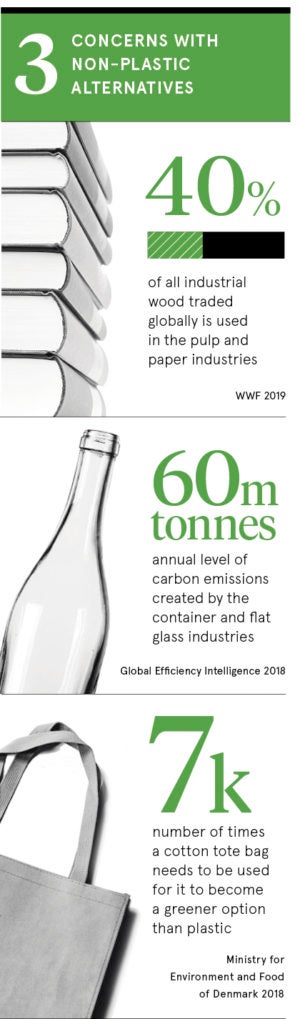

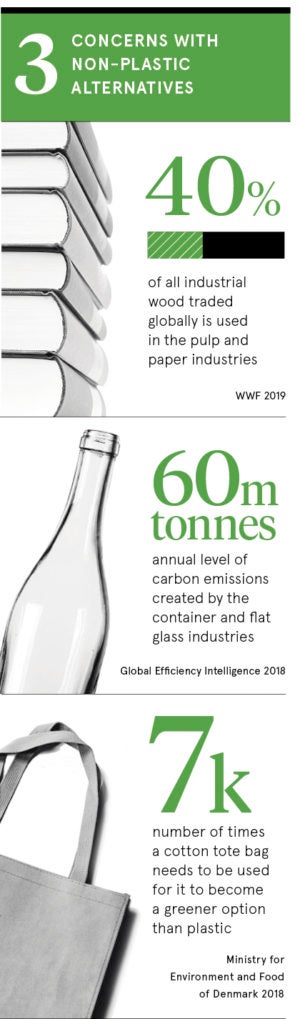

Plastic packaging, as we now all know, is problematic. Yes, it’s super useful for keeping products fresh and insulated. But its utility is offset by its impacts: overflowing landfills, ocean waste, microplastic pollution, and so on. So is it time to start considering alternatives? Absolutely. But non-plastic packaging isn’t without its environmental issues either.

Cardboard alternatives to plastic packaging

Cardboard should be the dream packaging product. And, in many ways, it is. It’s light while strong, easy to recycle and dependent on those great climate regulators: trees. It’s what happens before your boxed-up Amazon purchase lands on your doorstep that’s the problem. At the crux of the issue are commercial timber plantations, many of which are now located in the global south.

Plantations might be good for the climate, “carbon sinks” the scientists like to call them, but they aren’t nearly as great for the local habitat or, very often, for local communities.

“Plantations are constantly expanding into new territories, where biodiversity is replaced with monocultures of trees,” says Maria Ehrnström-Fuentes, a forestry specialist at the Hanken School of Economics in Finland.

The fast-growth tree species that go into pulp production, the base for cardboard, are very thirsty, resulting in water shortages, she adds. Smallholder farmers can also find themselves displaced by large-scale commercial forestation.

How to make cardboard responsibly

In response, the pulp and forestry industries have developed a variety of sustainability certification schemes to demonstrate their efforts to mitigate such negative impacts.

The best-known certification is run by the Forest Stewardship Council. Certified producers are required to show they meet ten core rules, which cover everything from avoiding environmental damage to respect for indigenous lands.

Conservation charity WWF has gone one step further, developing a set of good management principles specifically for the pulp and paper industry. The New Generation Plantations (NGP) initiative pushes participating companies to learn from one another about how best to address challenging issues.

As a basic starting point, plantations should never replace natural forests, according to NGP. Ideally, they would also be established on degraded areas with low conservation value and would make a positive contribution to local people’s lives.

An illustrative example is the Brazilian pulp and paper firm Fibria, which works with local charities in the south of Brazil to help establish community-owned tree nurseries. Another is Finland’s Stora Enso, which has set aside more than 100,000 hectares of its concession in Brazil’s Atlantic rainforest for conservation.

Glass alternatives to plastic packaging

One of the beneficiaries of the backlash against plastic packaging is glass. This time-honoured alternative is seeing steady demand growth in a range of sectors, from food and beverage to cosmetics, perfumery and pharmacy, according to the European Container Glass Federation (Feve).

One of the beneficiaries of the backlash against plastic packaging is glass. This time-honoured alternative is seeing steady demand growth in a range of sectors, from food and beverage to cosmetics, perfumery and pharmacy, according to the European Container Glass Federation (Feve).

As with cardboard, glass has the benefit of being highly recyclable. Furthermore, using existing glass in the manufacturing process allows for a lower melting temperature, which in turn lead leads to lower energy-related emissions.

Yet the carbon intensity of glass production still remains high. The container and flat glass industries, which account for 80 per cent of all glass, emit more than 60 million tonnes of carbon emissions a year, according to Global Efficiency Intelligence.

Energy efficiency measures are slowly helping bring this down over recent years. In Europe, for instance, almost all glass factories are now equipped with natural gas as opposed to more polluting fossil fuels such as diesel.

Glass producers invest to cut carbon emissions

The European glass industry annually invests €610 million in waste heat recovery systems and other decarbonising measures, says Feve spokesperson Michael Delle Selve. These initiatives resulted in a 5 per cent reduction in carbon emissions between 2009 and 2015, Feve says.

What’s more, industry data shows that CO2 emissions have been cut by 70 per cent in the past 50 years.

For ethical water brand Belu, which gives 100 per cent of its profits to WaterAid, the focus should be on avoiding single-use packaging wherever possible, be it glass or plastic; Belu uses both.

In a frank admission, Belu’s chief executive Karen Lynch says the best option for eco-conscious consumers is to drink tap or filtered water from a refillable, non-plastic bottle.

“You may give yourself a big high five for being plastic-free, but you could triple or even quadruple the carbon emissions created if you opt for a switch to single-use glass,” she says.

Cotton alternatives to plastic packaging

Meanwhile, if there’s one single item that earns the universal ire of environmentalists, it is the single-use plastic bag. For many, cotton tote bags are seen as a more sustainable alternative. But are they?

Not if a recent study commissioned by the Danish government is to be believed. Cotton bags need to be used around seven thousands times to become a greener option than plastic, according to the study.

Why? Because cotton is a thirsty, land-hungry crop that typically requires large volumes of polluting fertilisers and pesticides. Infrastructure for recycling cotton is also scarce.

Leading the charge in making cotton more sustainable is the Better Cotton Initiative (BCI). This industry-backed group works with almost two million farmers around the world, encouraging them to adopt more sustainable practices, such as using less water and fewer chemicals.

Even so, less than 20 per cent of cotton is currently grown in a way that actively protects people and the planet, says BCI chief operating officer Lena Staafgard. “BCI seeks to change this and is striving to transform cotton production from the ground up,” she says.

Cotton’s environmental footprint is a concern for many

For now, however, even purveyors of tote bags are wary of overly endorsing them. Few companies are more eco-aware than Rotterdam-based Bio Futura, a wholesale provider of plant-based packaging products. On its product list are Fairtrade-certified cotton bags made from at least 70 per cent organic cotton.

“Under no circumstances do we want to mitigate consumer concerns about the environmental footprint of cotton in general; we rather encourage our customers to ask critical questions about our products and their impact,” says Ekaterina Smid-Gankin, sustainability consultant for Bio Futura.

Ms Smid-Gankin says finding zero-impact packaging solutions is, as yet, not possible. That’s as true for cardboard and glass as it is for cotton. Even so, anything is better than plastic, she maintains. Her core message: “Reuse, reuse, reuse and, where possible, reuse again.”

Cardboard alternatives to plastic packaging

How to make cardboard responsibly

Glass alternatives to plastic packaging