After a slow start, the UK is set to accelerate its carbon-capture initiatives, with the government aiming to position itself as a world leader in this field by as soon as November, when the UN is due to hold its COP26 climate conference in Glasgow.

The plan includes growing more trees; restoring peatlands, which are big absorbers of CO2; and developing technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS).

Expert groups such as the Climate Change Committee, an independent public body that advises the government, agree that the world will not hit its net-zero targets for carbon emissions without the help of CCS.

“The committee has consistently stressed the importance of CCS in achieving net zero,” says Tom Dooks, communications officer at the Climate Change Committee. “For industries such as cement production, it’s the only viable technology for reducing emissions to the extent required. All credible pathways through which the UK could reach net zero domestically involve a significant role for CCS, especially for greenhouse gas removal, to help offset some of the emissions from those sectors where abatement will be most difficult.”

CCS is not an option but a necessity to address climate change

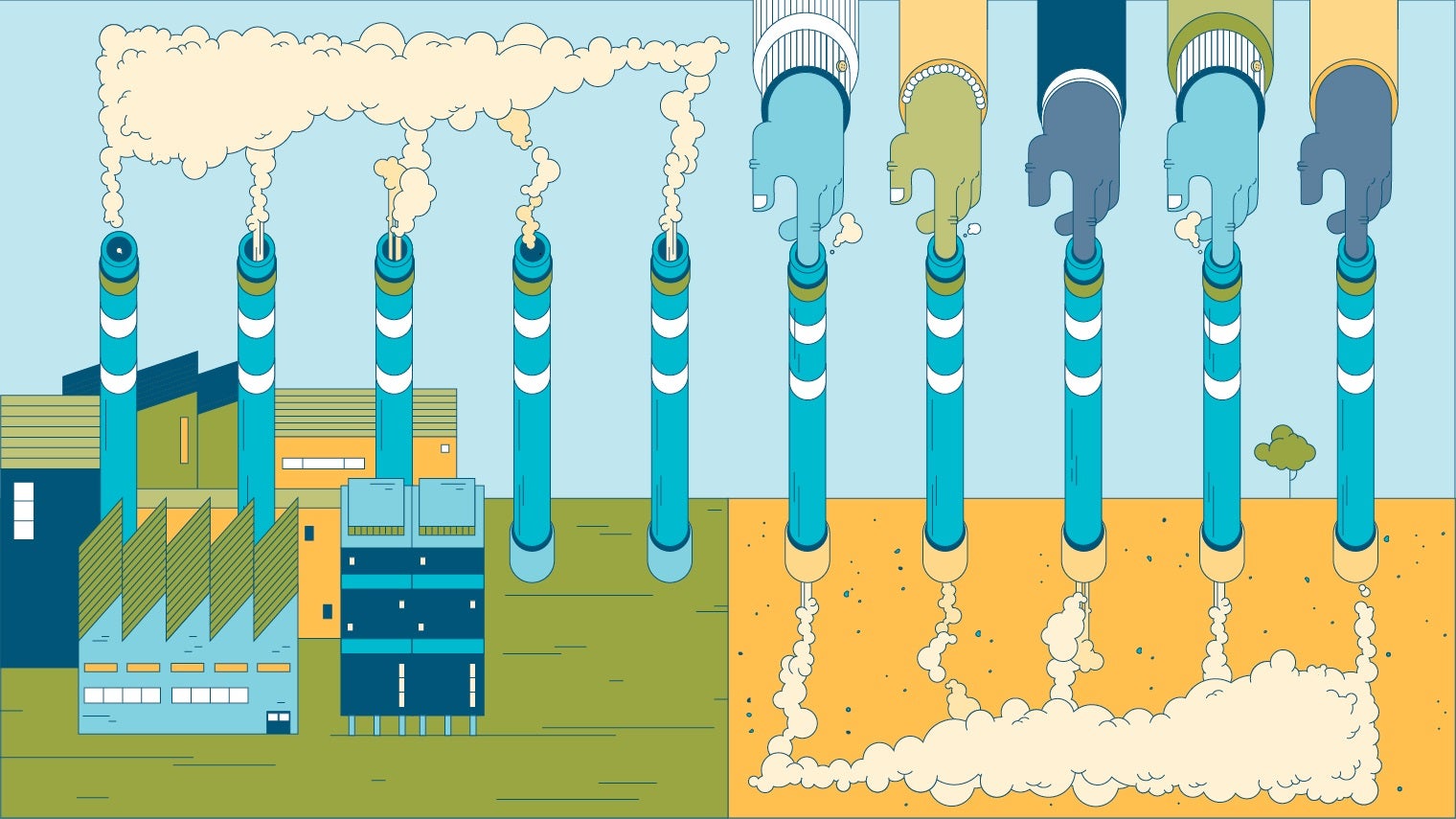

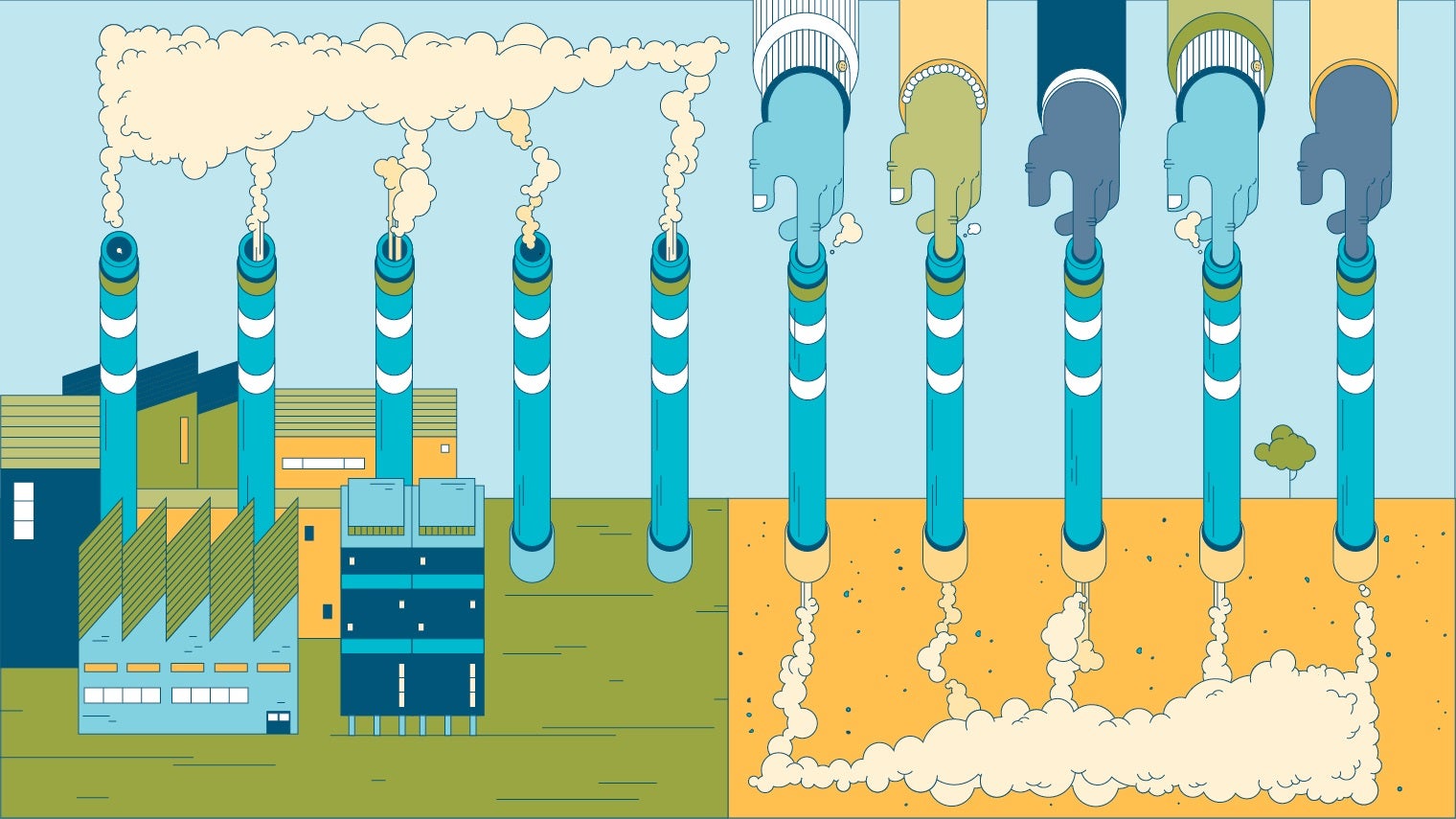

The technology can be used to extract CO2 from industrial processes or directly from the air and transport it to be stored deep underground, where it cannot contribute to global warming.

“CCS potentially has a big role to play in several applications by 2050,” Dooks says. “These could include the removal of greenhouse gases, the production of hydrogen and the generation of power. While global progress has been slow, there are now 43 large-scale projects in operation or under development around the world, but none in the UK.”

British CCS projects

The UK does at least have CCS projects at the planning stage. These will be based on the Humber estuary and along Scotland’s North Sea coast.

Shell has started working in the latter location with the Storegga Group and Harbour Energy on the Acorn Project. This will initially capture CO2 from industrial sites in Scotland and store it deep under the seabed. Any gas that isn’t stored could be used in the manufacture of plastics, fertilisers, fuels and even fizzy drinks.

Sinead Lynch, Shell’s country chair in the UK, says that CCS will be “vital” in tackling climate change, stressing that the technology enables a producer of fossil fuels to be part of the solution by reducing or offsetting carbon emissions when these cannot be avoided.

“CCS is not an option but a necessity to address climate change,” she says. “We do need to ramp up investments in this technology. There is no doubt that the scale required ranges from large to huge. The use of renewable energy sources on its own won’t get us to net zero, which is why we need carbon capture.”

Public-private partnerships

Dooks notes that achieving carbon neutrality will “require new infrastructure to be built. This must be a partnership between government and business. CCS can benefit the economy, especially by levelling up areas across the country. The government will need to lead on infrastructure development and offer long-term contracts to encourage investment in carbon-capture plants.”

For instance, the government has provided £250,000 in funding for Sizewell C, the planned nuclear power station in Suffolk, to develop technology that will remove CO2 directly from the atmosphere once the plant is up and running as expected in 10 years’ time. The project is being developed by a consortium including CCS experts from the University of Nottingham, Atkins, Strata Technology and Doosan Babcock.

Professor Colin Snape, director of the university’s Energy Technologies Research Institute, believes that the use of CCS in the UK will focus on heavy industries and the production of gas – if gas remains a significant part of the country’s energy mix.

“CCS has to feature on the COP26 agenda,” he says. “If gas does stay in the mix, it will need to be decarbonised. But industrial processes emit huge amounts of CO2 as well, so CCS could be playing a significant role in those by 2040.”

The use of renewable energy sources on its own won’t get us to net zero, which is why we need carbon capture.

Snape adds that the main problem with CCS projects is that they are “huge, requiring a lot of money up front to build the plant and pipeline”. But he suggests that it should be possible for industrial clusters to pool their resources and share infrastructure.

Dooks agrees. “Developing regional CCS clusters will be the first step,” he says. “To enable that, there will need to be appropriate incentives – and the government is working on a series of them to support different parts of the chain.”

The first of these, known as the CCS transport and storage regulatory investment model, will fund the development of shared infrastructure, Dooks explains.

“There will also be a series of business models to support CO2 capture from different sources: industrial, power generation and hydrogen production,” he says. “Such incentive models will need to be finalised and contracts awarded before companies can make their final investment decisions and start construction. The government recently took its first step towards awarding these with an ‘expression of interest’.”

Although it has yet to activate a single CCS facility, the UK is already sharing technical knowledge with a number of countries and also the EU, according to the Climate Change Committee. Its activities include: leading an international working group to expedite the deployment of CCS; participating in Mission Innovation, a global R&D initiative focusing on clean energy; and collaborating, via the UK CCS Research Centre, with equivalent groups in Australia, Canada, China, the Netherlands, South Korea and the US.

“COP26 will require the UK to demonstrate its credibility to the world, but it can be the chance to lead the world towards net zero,” Dooks says. “This will require many technologies – including CCS – to be discussed and knowledge to be shared.”

After a slow start, the UK is set to accelerate its carbon-capture initiatives, with the government aiming to position itself as a world leader in this field by as soon as November, when the UN is due to hold its COP26 climate conference in Glasgow.

The plan includes growing more trees; restoring peatlands, which are big absorbers of CO2; and developing technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS).

Expert groups such as the Climate Change Committee, an independent public body that advises the government, agree that the world will not hit its net-zero targets for carbon emissions without the help of CCS.