Cobalt is vital for jet engine alloys and everyday electronics, like smartphones and laptops. But it’s the chemical element’s part as a key component in lithium-ion batteries (LIB), accounting for around 20 per cent of the raw material needed for cathodes, which has seen interest in the commodity reach feverish heights.

Presently the electric vehicle (EV) battery market only accounts for around 10 per cent of total cobalt usage, but sales of EVs are skyrocketing – up 58 per cent globally in 2017, according to Darton Commodities – driven primarily by China.

The huge sums of money being pumped into EV development by the automotive sector and announcements of several new LIB production factories planned has shaken the market.

Because eventual widespread EV adoption is now considered a certainty, with some reports forecasting the technology will reach price parity with conventional cars by 2025, since January 2016, cobalt’s market price has surged around 280 per cent, Darton Commodities says.

The race to secure supplies of cobalt has become urgent and China has taken the lead. Chinese chemicals firm GEM recently secured a deal with Glencore, the largest producer globally, for more than 50,000 tonnes of cobalt over three years, which represents around a third of the company’s total planned production during this time.

As the race for cobalt revs up, its production is getting evermore complex

Apple has reportedly been in talks to buy long-term supplies of cobalt directly from miners for the first time ever and Volkswagen has had several failed attempts to lock in supply deals.

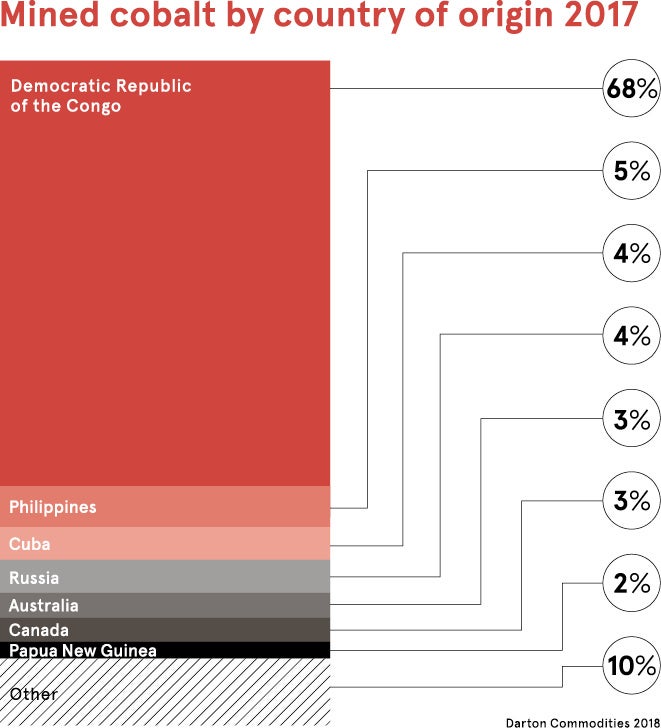

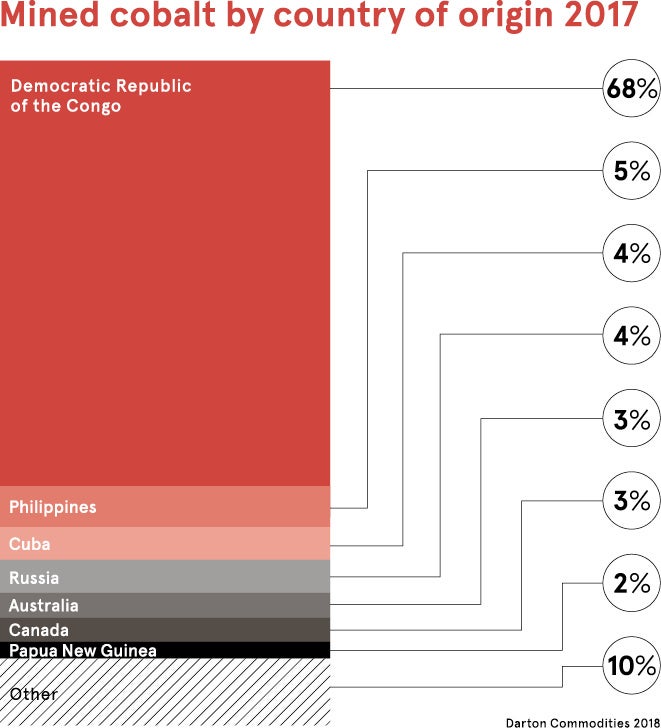

As the race for cobalt revs up, its production is getting evermore complex. Most major cobalt producing mines are located in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) where roughly 52 per cent of the world’s reserves lie in the African copper belt that also includes northern Zambia. Last year, 67 per cent of global mined supply came from the DRC, which is seen as politically insecure.

The next two big production expansion projects are also in the DRC: Eurasian Resources Group’s Roan Tailings Reclamation (RTR) project and Glencore’s Katanga, both of which would increase the concentration of cobalt coming from the country to around 75 per cent of the global total.

Knowing it effectively has a monopoly, the DRC government recently passed a new mining code that will, when enacted, ramp up royalties on the commodity from 2 to 10 per cent if it is labelled as “strategic”. An adviser to the mining minister has told Reuters that this is likely. Other new terms include a 50 per cent super profit tax on what the government deems excess profits and a 10 per cent capital stake of a company to be held by Congolese private citizens.

A delegation of mining executives was visiting the DRC negotiating for the new terms to be revised.

Nick French, director at Cobalt27, which manages a portfolio of cobalt royalties as well as physical reserves, says overall there will be three main impacts of the new code: an upward pressure on price; a disincentive for new investors; and potential postponement of projects coming online.

Glencore, for example, could delay production at Katanga or choose to stockpile reserves as ongoing negotiations provide little incentive to rush the project, even if demand is growing.

Peter Ruxton, principal at Tembo Captial, a private equity firm with interests in Nuzuri Copper, which owns the Kalongwe Copper Cobalt project in the DRC, says the new mining code will mean fewer projects are economically viable in the country, especially the smaller ones. Furthermore, if copper, which cobalt is a by-product of, is also branded strategic, the economics will be even more challenging.

“In high-risk destinations like the DRC, companies look for high rewards. Under these new terms, it will become difficult to justify investment there based on the risk-reward equation,” says Mr Ruxton, adding that the firm will not seek future investments if nothing changes.

Increasing taxation in the DRC, shortage of supply, coupled with China’s growing dominance and an anticipated exponential increase in demand have created a “perfect storm”, says Mr French. “All these factors need to be seen holistically. Individually they may not have had a major effect, but the cumulative impact is significant,” he says.

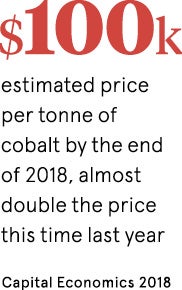

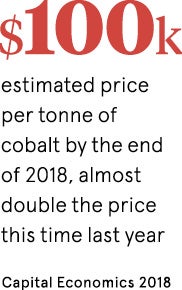

Most major analysts agree there will remain an upward pressure on price. Capital Economics’ end-of-2018 forecast for prices is $100,000 per tonne, up from $94,000.

Most major analysts agree there will remain an upward pressure on price. Capital Economics’ end-of-2018 forecast for prices is $100,000 per tonne, up from $94,000.

Could high prices and a shortage of supply negatively impact the forthcoming EV revolution? Potentially, but price is much less an issue than access to supply.

Andries Gerbens, head of sales at Darton Commodities and author of the firm’s 2017-2018 Cobalt Market Review, says with higher prices there is only likely to be a $70 to $80 deferential per battery from today’s prices, which wouldn’t have a huge impact on the overall cost of an EV. Furthermore, the expenditure associated with battery technology is routinely falling.

High prices could greenlight production not normally considered economically viable and bring more supply on to the market, but that would be much further down the line.

For now, Mr Gerbens says Katanga and RTR, the latter anticipated to come online in 2019, will ease present shortages in the market, but after 2020, around 2022, when the exponential increase in demand for EVs is expected to kick off, is when the deficit will widen. Especially as near-term surplus supply will probably be pre-emptively purchased, as is already happening.

“What will happen then? Will car manufacturers be unable to produce the number of cars they want to or will there be new technology that designs cobalt out of lithium batteries altogether?” asks Mr Gerbens.

The latter is possible, though he doesn’t back this outcome. Perhaps EV predictions will fall short? Or, as many are starting to suspect, the majority of EVs will be made in China by the Chinese companies who currently have dominance over cobalt supply.