The winds of change are blowing more than just a bit of plastic in the breeze; they’re now whistling through the halls of Westminster. The government has just wrapped up an ambitious consultation, the first in ten years, on reforming how we deal with waste packaging. Industry and consumers can expect a radical shake-up.

In a bid to breathe new life into a creaking system, significant intervention is expected in the form of policy and fiscal drivers, amid great expectations within the industry. Some are calling it a once-in-a-generation opportunity to revitalise recycling and use of resources, counter littering and give a significant push towards a circular economy.

“This comes after the UK parliament declared a climate emergency and the Committee on Climate Change recommended that the country aims for net zero carbon emissions by 2050,” explains Ben Stansfield, partner at law firm Gowling WLG. “There is phenomenal momentum here. I think a lot of what’s being proposed by the government will be adopted.”

Current recycling system is letting the UK down

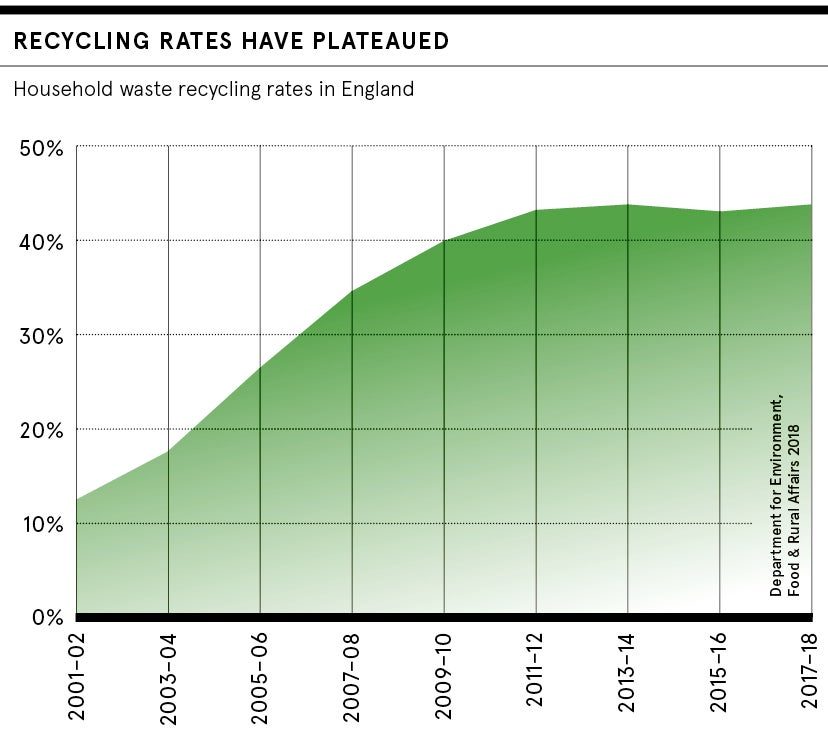

And there’s a need for change. Recycling rates have plateaued in the UK. We still have a system that favours exporting 50 per cent of our waste with limited incentives for domestic reprocessing. The system of collection is complicated, localised and fails to provide local authorities with enough financial support. At the same time, a lot of useable packaging and materials still end up in landfill. A lack of accountability and transparency is also apparent.

“The government feels the existing regulations do not deliver what we want them to do in the future and to help the UK meet more challenging targets for recycling, as well as increase the revenue that comes from the system,” says David Honcoop, managing director of Clarity Environmental.

The Resources and Waste Strategy is the 124-page blueprint from the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, which will evolve into new laws soon. In the process, everybody will be impacted in some way.

At its core is the “polluter pays” principle. Businesses can expect so-called extended producer responsibilities for the packaging they churn out. UK companies currently experience lower costs for compliance compared with producers in many other European countries.

Current scheme is confused and confusing

It means that only 10 per cent of the costs for recycling schemes come from producers themselves through compliance systems, such as packaging recovery notes, or PRNs, which provide evidence waste packaging material has been recycled into a new product; the rest is funded by local authorities and central government.

“We have been calling for waste producers to pay for their recycling for many years now. What this should do is force manufacturers and retailers to ensure the packaging they put on the market is easily recyclable,” says Simon Ellin, chief executive of the Recycling Association.

“If we get the system right, consumers will have easy labelling that tells them the packaging is recyclable, what bin to put it in and then we will get much higher-quality recycled material to be used in new products.”

At present there are many variables involving a mind-boggling array of local authority collections and packaging with highly variable recycling qualities. Complexity hinders the system, but this could change. “A well-designed scheme needs to be simple for everyone to understand,” says Mr Ellin.

“The principle that local authorities will collect core packaging, such as plastic bottles and containers, paper and card, glass and cans, is a good one. Packaging manufacturers and retailers will need to match this list with the products they put on the market or face additional charges.”

New recycling system puts accountability on waste producers

The shake-up is likely to be rolled out within four years, with a revamped and simplified labelling system; none of the “check locally” labelling, which has been deemed a barrier to better recycling. A deposit return scheme for single-use drinks containers and a tax on plastic packaging with less than 30 per cent recycled content is also in the strategy.

UK reprocessors have long been lobbying for changes to the current PRN system, which they believe incentivises materials being sent abroad.

“One of the biggest risks in the redesign is that we see an increase in costs for producers and ultimately consumers, but a failure to improve our existing recycling system,” says Robbie Staniforth, head of policy at Ecosurety.

“A well-designed scheme will recognise the true costs of packaging, as well as the costs of a transparent, effective recycling system. We must create a level playing field for all involved, as well as provide extra funding to local authorities, which are a critical cog in the recycling machine.”

All this is likely to require complicated manoeuvres in industry, including mechanisms that transfer the cost of recycling to those who produce packaging in the first place. Agreement from each link in the supply chain and co-ordination will be crucial to make a new, consistent system work.

“It is vital businesses start preparing now,” says Mr Honcoop. “We’ve already seen an increase in the cost of complying with packaging regulations over the last 12 months and, without changes in behaviour of how businesses view their packaging obligations, the new proposals could have huge implications.”

A year after BBC TV’s Blue Planet II and the subsequent backlash against plastic, consumers are already aligning themselves with brands that take this issue seriously. “By embracing change, producers will be protecting the future of their business as well as the environment,” Mr Staniforth concludes.

Current recycling system is letting the UK down

Current scheme is confused and confusing

New recycling system puts accountability on waste producers