Few businesses can rival the 2020 pandemic success of Loop. Such has been customer demand that the innovative, online refillable packaging service has just opened across all forty-eight contiguous US states, up from a mere nine when it launched in May last year.

Loop, which is also available in the UK and France, is fast becoming the poster child of a reusable packaging trend that is spreading globally as consumers increasingly seek out alternatives to single-use plastics.

“From the consumer demand we’ve seen around the world, the growth of refill and reuse models promises to be extraordinary,” says Stephen Clarke, head of communications for Loop Europe.

New companies closing the loop

In addition to its eco-friendly credentials, Loop has developed an ecommerce platform where consumers can buy household brands – products from Ecover, Danone, Coca-Cola and Nivea are among those on offer – rather than flogging its own-brand (read less trusted) alternatives.

The system works like any other online shopping experience: you log on, select your item and pay. The difference is your products then arrive in a recyclable padded container – the Loop Tote – which acts like a recycling bin. In go the empty bottles and then, courtesy of one of Loop’s retail partners – Tesco in the UK, for instance – back they go to Loop’s parent company TerraCycle for recycling.

The strong product value that consumers experience via Loop helps build on people’s growing willingness to try solutions that tackle the wastefulness of single-use packaging, says Tim Debus, president and chief executive of the US-based Reusable Packaging Association.

“Active support and participation from consumer product brands and retailers are key ingredients to creating product value and connecting with consumers on the positive experience,” he adds.

A report last year from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation cites 69 refillable packaging ventures in markets around the world, from water refill vending machines, such as Dasani’s pilot PureFill stations, through to deposit-return schemes like the refillable gas cylinder service offered by sparkling water venture SodaStream.

3 steps to refillable packaging: test, learn, refine

Global consumer good giant Unilever is one of those getting in on the act. In addition to producing some refillable versions of its own best-selling brands, like a concentrated version of its Cif bathroom cleaning spray, it is partnering with other reuse specialists to help them scale.

An illustrative example is its support for Algramõ in Santiago, Chile. The startup uses electric tricycles to deliver a selection of Unilever’s homecare products to people’s homes. On arrival, the products are dispensed into returnable containers by an automated dispensing unit, which is connected to an app that allows users to place their order and pay virtually.

“There isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. To deliver a range of options that work, we continue to adopt a ‘test, learn and refine’ mentality,” says Richard Slater, chief research and development officer at Unilever.

Hitting on the right answer promises lucrative rewards. If just one fifth of existing plastic packaging were to be replaced by reusable or refillable alternatives, it could open up a $10-billion business opportunity, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimates. PepsiCo’s 2018 purchase of SodaStream for $3.2 billion offers an inkling of the money at stake.

The eco-concerns and general adaptability of younger consumers put them in the vanguard of the refillable packaging movement. A study of 2,000 16 to 24 year-olds by market analysis firm GlobalData late last year found that more than two-fifths (44 per cent) had used a refill station in the previous 12 months.

Examining the “COVID effect”

The coronavirus pandemic has had a “dampener” effect on some initiatives, as consumers return to single-use packaging due to hygiene concerns, Emily Salter, retail analyst at GlobalData, concedes. She gives the example of Waitrose’s decision not to extend its popular Unpacked trial, which has seen a dedicated refillable zone and a frozen goods pick-and-mix option introduced into four pilot stores.

Helping offset health concerns, however, has been the huge appeal of doorstep refillable services during lockdown. Algramõ, for example, which also dispenses a pet food brand for Nestlé, reported a 356 per cent increase in demand between April and June while Santiago residents were confined to their homes.

Welsh startup Splosh experienced much the same. The concentrates specialist, which sells a range of home essentials, from shower gels to toilet bowl cleaners, has seen demand for its subscription-based service peak in recent months. “At times, we’ve struggled to cope with demand,” says the firm’s founder Angus Grahame.

Is ”ease” the answer?

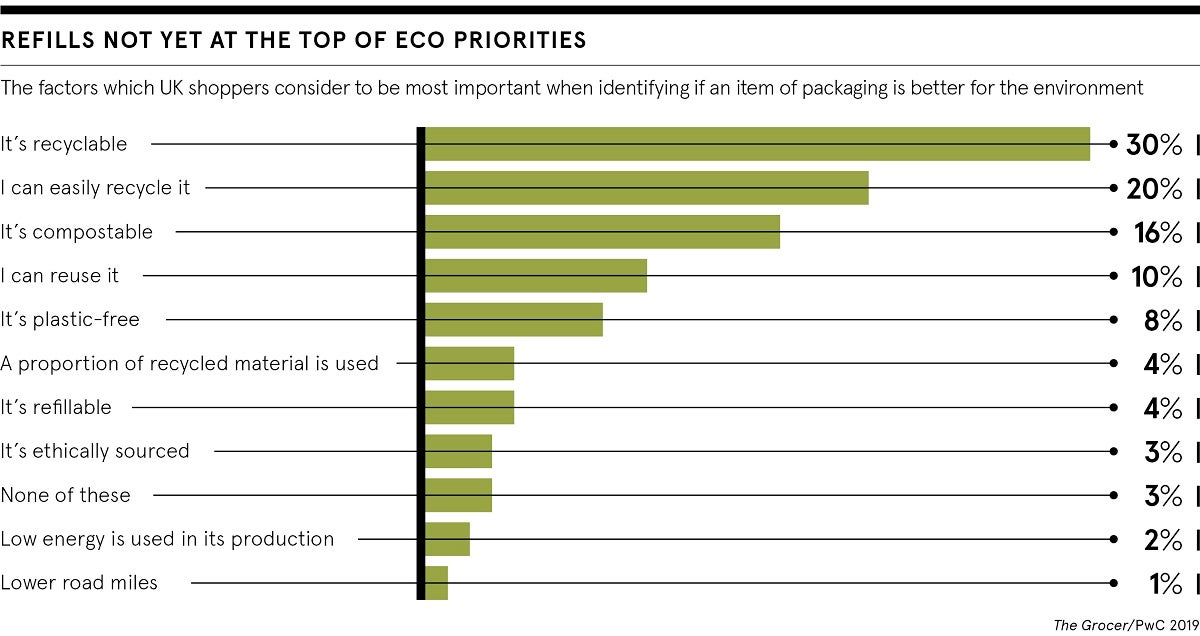

Another reason behind the success of Splosh and other refillable services like it comes down to one word: ease. A small minority of consumers are motivated enough by environmental concerns to go the extra mile to limit their use of plastic packaging, says Annette Lendal, a circular economy expert at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Most, however, are not.

Making refillable packaging easy to use, therefore, is critical. In Splosh’s case, it has designed a delivery package (recyclable of course) that allows it to post its product concentrates through conventional letterboxes, avoiding the need for customers to be at home.

Digital technology is also making refilling easier for customers. UK campaign group City to Sea, for instance, has developed an easy-to-use app that identifies the 20,000 or so locations where people can fill up their water bottles for free.

“All our campaigns are rooted in behaviour change theory that will inspire, nudge and provoke people into taking action on tackling plastic pollution. Making an action easy for people to do is absolutely a core component of this,” says campaign manager Steve Hynd.

In a similar vein, this summer it launched a campaign for the reintroduction of reusable cups and containers by coffee shops and food outlets, many of which desisted from doing so for health reasons after COVID-19 hit.

Other ventures are experimenting with consumer incentives to win over everyday punters. Chile’s Algramõ, for instance, offers loyalty rewards for reusing its packaging, recoupable via its dispensing machine. UK organic food retailer Abel & Cole, meanwhile, throws in a freebie to loyal customers, offering the tenth refill of the same product without charge.

We need to look beyond premium designs and focus on plainer, more standardised packaging

The future means aiming for mainstream

Refillable schemes can be as easy and attractive as possible, but too many still focus on the premium end of the market, says Lendal at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. The trend is understandable. Refillable options not only require rejigging standard packaging design, but also a re-engineering of how products are dispensed, delivered and returned; so-called reverse logistics.

The trick is to ditch bespoke solutions, she says, and instead invest in standardised reusable packaging that is physically robust, simple to clean and interchangeable between brands.

“To reach the mainstream, we need to look beyond premium designs and focus on plainer, more standardised packaging. The big brands get this and it’s something I think we’ll now start to see increasingly,” Lendal concludes.

Few businesses can rival the 2020 pandemic success of Loop. Such has been customer demand that the innovative, online refillable packaging service has just opened across all forty-eight contiguous US states, up from a mere nine when it launched in May last year.

Loop, which is also available in the UK and France, is fast becoming the poster child of a reusable packaging trend that is spreading globally as consumers increasingly seek out alternatives to single-use plastics.