Amid the clamour for cobalt and lithium, two commodities needed for the development of electric vehicles, there is also fresh demand for other minerals.

According to Danny Malchuk, president of operations at Minerals Americas, a regional subsidiary of mining giant BHP, the global electric vehicle fleet could rise to an estimated 140 million by 2035 from about one million today.

But rather than making a major move into lithium and cobalt, Mr Malchuk says BHP will instead look for copper projects. “We want more copper resources in our portfolio,” he told an audience of industry specialists gathered in London.

It’s a low-risk approach to an emerging new technological space that’s nevertheless likely to pay off. That’s because around 105 kilogrammes of copper will be required for each new electric vehicle made, according to Mr Malchuk.

Substantial amounts of lithium and cobalt may be required too, but here the commercial risk is greater, because the future of the supply-demand dynamic is so hard to read. In the case of copper, First Quantum’s $6.3-billion Cobre Panama mine is the only new large project likely to come on stream in the next couple of years.

With lithium it’s different. While it’s true the lithium price has more than tripled in the last three years and continues to trade at comfortably above $20,000 a tonne, it’s also true that there is a lot more lithium around than copper.

For one thing, the Chinese are emerging as a major producer and it’s hard to predict how Chinese supply will affect markets when production data is often opaque.

But perhaps more critical than this is the straightforward abundance of lithium in the earth. It is, in fact, the third most plentiful element.

So for now the major miners are staying out of the lithium business, content to let specialists and speculators take the risks on a possible future glut.

Instead, the field has been left clear for those with established market presence, such as the $10-billion American company Albemarle and the Chilean company Sociedad Química y Minera, which is the world’s biggest supplier.

A plethora of smaller explorers and developers have also arrived on the scene, looking to capitalise on predictions like Mr Malchuk’s. But the risks are already apparent.

Shares in European Metals Holdings, a company with a major development project in the Czech Republic, have fallen by more than 75 per cent since highs hit last year.

Increased production of electric vehicles will not offset the forecast increase in lithium supply

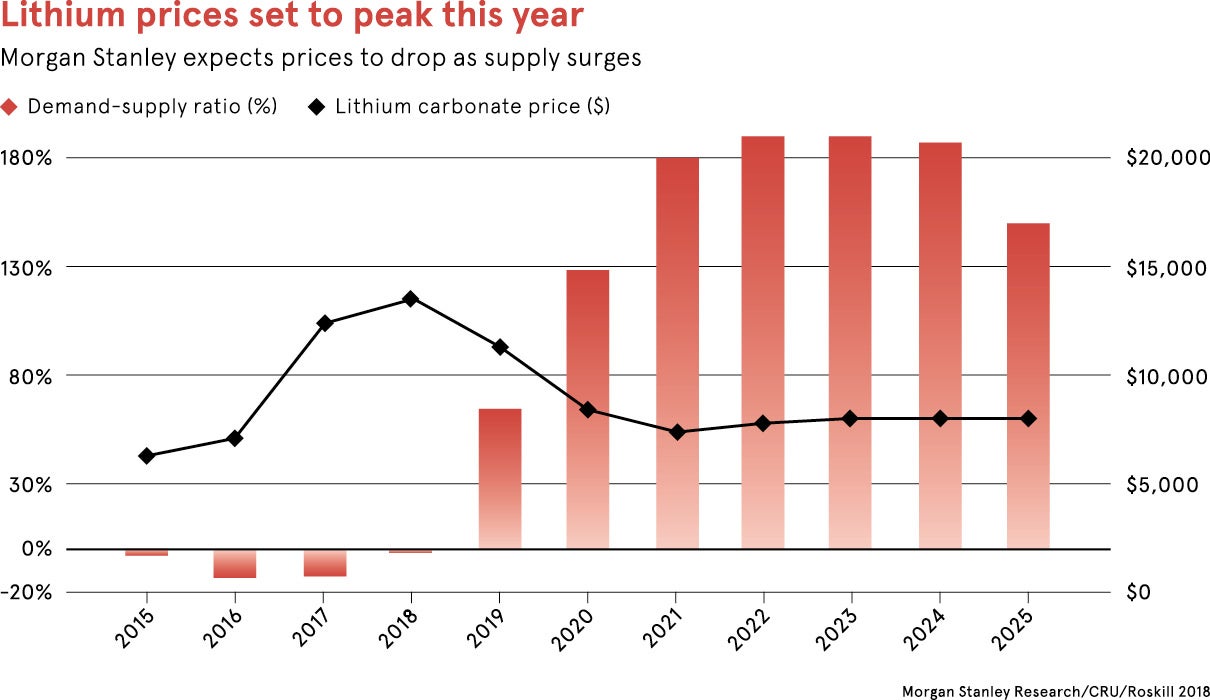

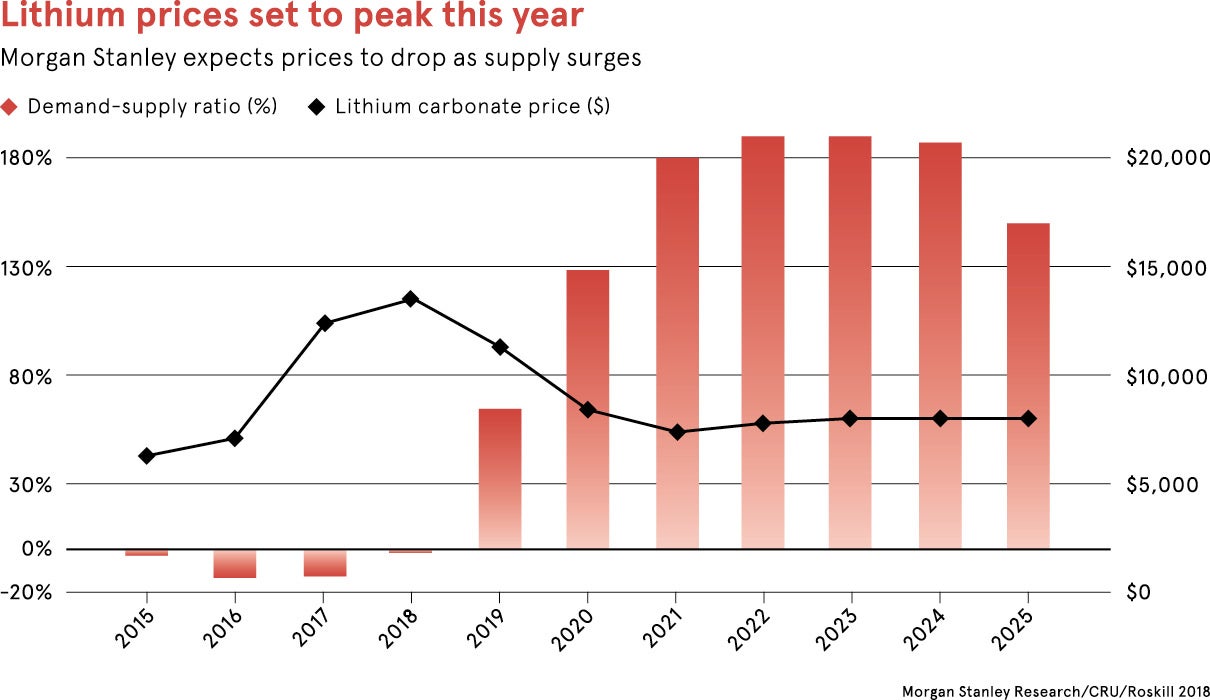

In February, Morgan Stanley forecast that the lithium price would drop by 45 per cent by 2021, as supply from the major producing region, the so-called Lithium Triangle in South America, steps up rapidly.

Increased production of electric vehicles will not offset the forecast increase in lithium supply, Morgan Stanley analysts forecast.

Experienced industry investors are already following that line. Julian Treger, a former fund manager at Audley Capital, who now runs boutique mining finance house Anglo Pacific, says he’s wary of metals like lithium and cobalt that have been caught up in the electric vehicle hype. “We want to grow in copper, nickel and zinc,” he says.

These are metals that are likely to be used in new technologies too, but which also have a broad appeal across the board in older sectors such as construction and engineering.

But while there is wariness about so-called “fashionable” metals, there is also cautious positioning taking place.

Glencore, the mining and trading major, produces more cobalt than any other company, but that’s primarily because the cobalt comes as a by-product of its Congolese copper production.

Copper is far more central to Glencore’s offering. The metal leads when the company is briefing investors on production highlights and accounts for the major proportion of its profits, alongside zinc. In the 12 months to December 2017, Glencore produced 1.3 million tonnes of copper and just 27,000 tonnes of cobalt.

Nevertheless, like many of the major companies in the industry, Glencore remains open to new ideas.

“The electric vehicle upheaval continues to unfold, with the scale of market penetration, and investment by battery and automotive manufacturers and infrastructure players adjusting progressively upwards,” the company says. “This provides an additional dimension of future demand growth for a number of our key commodities.”

Meanwhile, another of the world’s largest mining companies, Russia’s Norilsk Nickel, has signalled its openness to the opportunities presented by the new battery market.

Gareth Penny, Norilsk’s chief executive, expects the biggest near-term market will be in hybrids rather than electric vehicles, and he is positioning his company accordingly to supply both nickel and palladium into this market.

This is partly a market-facing response to a perception that the rise in electric vehicles will decimate the market for catalytic converters and the profitability of mining platinum and palladium, which are the key elements that go into them. But there’s more to it than that.

“Norilsk will definitely look at some form of partnership at different levels in the industry to maximise the value of its product,” says Mr Penny, citing a potential relationship with BASF, the European chemicals company, as a possible route forward.