The fashion industry’s impact on technology has not yet surpassed its high point of 1804 with the invention of the mechanical loom. As the world’s first programmed machine, the Jacquard loom revolutionised manufacturing, predating and inspiring Babbage’s inventions, and forming the basis for modern computing.

The fashion industry’s impact on technology has not yet surpassed its high point of 1804 with the invention of the mechanical loom. As the world’s first programmed machine, the Jacquard loom revolutionised manufacturing, predating and inspiring Babbage’s inventions, and forming the basis for modern computing.

In the intervening centuries, the fashion industry, now valued at $2.4 trillion, has not relied on research and development to stay competitive and today’s manufacturing would be familiar to any 19th-century Luddite.

“We make a shirt the same way we did 100 years ago and it’s insulting,” according to Kevin Plank, founder of sportswear brand Under Armour. But this is set to change. Mr Plank, among others, is asking: “How can we use technologies to make a better product and produce it more efficiently?”

Forced to innovate

Inertia around innovation in fashion is lifting. Forced by the encroachment of companies such as Amazon, which hopes with the acquisition of a made-to-order manufacturing system to increase its market share from 6.6 to 16 per cent by 2021, the industry is upping its game.

Tech giants, including Google (working with Levis) and Intel (Hussein Chalayan and Opening Ceremony), are seeking partnerships with fashion brands in a bid to scope out the next manifestation rivalling the smartphone. Fabrics with circuitry and sensing capabilities woven into their fibres could be an answer, turning human bodies into dispersed computers.

Meanwhile, after years in stealth mode, a quiet revolution in biotech is finally bringing new materials to market that will transform manufacturing. Instead of stitching components of clothing with needle and thread, by 2025 a garment could be grown in the laboratory with DNA.

Sustainability challenges

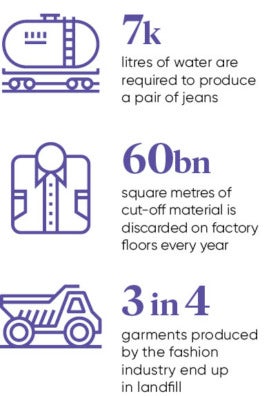

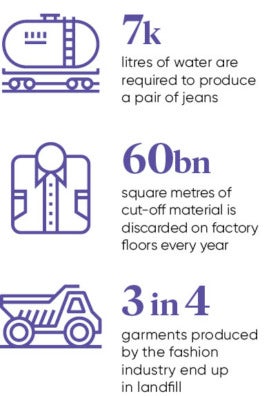

Looming behind this innovation is an impending crisis over resources and a long shadow cast by the industry’s dire environmental record, which positions fashion as second among the world’s most polluting industries after oil. A pair of jeans requires 7,000 litres of water to produce and tons of chemicals to dye. Annually, 60 billion square metres of cut-off material is discarded on factory floors. And a high-consumption, low-value model means that three in four garments, from an industry producing 80 billion each year, end up in landfill.

Alarmingly, synthetic fabrics – the 20th century’s main contribution to material innovation – could be more damaging to marine life than microbeads, which were recently banned from cosmetics. According to the University of New South Wales, microfibres from clothing such as fleece enter the water system through washing, make up 85 per cent of human-made debris on shorelines and are now entering food chains.

Instead of stitching components of clothing with needle and thread, by 2025 a garment could be grown in the laboratory with DNA

“Technology can enable sustainability,” says fashion technologist Amanda Parkes, and it’s a view that is increasingly shared across the industry. Dr Parkes recently joined Fashion Tech Lab, founded this year by Russian entrepreneur Miroslava Dumas, which will bridge the divide between fashion and technology, driving investment and product development, and creating partnerships between tech companies and big brands in luxury.

Couture, Dr Parkes notes, has the capacity to bear high costs of research and in surprising ways shares similarities with original science as its output is time intensive, its value is predicated on scarcity, and it is very expensive to produce. Indeed, in the luxury sector sustainability is fast beginning to occupy a position of cachet once held by artisanship and craft.

Looking ahead

The falling cost of biotech has caused a surge in material innovation. For millennia, humans have fashioned animal hides to make clothing, but New York based biofabrication company Modern Meadow designs, grows and assembles collagen into biofabricated leather materials. It is working with several major brands to make bespoke biofabricated materials of varying textures, stretch and thickness. These will be years in development, but the platform could be revolutionary.

“The way we construct our material means we can roll several separate processes into one, creating massive savings on water, energy and chemicals, like dyes and treatments,” says Suzanne Lee, Modern Meadow’s chief creative officer.

They will join exceptionally strong and lightweight fabrics made from spider silk, which have mythologised as far back as the Greek Fable of Arachne. Japan-based Spiber has made a one-off jacket with North Face, German AMSilk has produced sneakers for adidas and Californian Bolt Threads is working on an outdoor range for Patagonia. If taken up across the industry, the potential for system change could be enormous.

In a bid to break current manufacturing and supply models, mass-market brands such as adidas, along with Uniqlo and Under Armour, are experimenting with in-store made-to-order 3D printing for shoe soles, and 3D knitting for shoe uppers and garments. At the same time, the world’s first fully automated garment making machinery, Sewbo, hopes to make fashion a high-tech industry and even return production to the United States.

Tech-enhanced apparel could address one of the most fundamental functions of clothing in temperature-controlled textiles, which Dr Parkes predicts are not far off. “The whole point of wearing clothes is to regulate your body temperature and protect you,” she says. “Anything that can warm or cool as you need is obviously incredibly useful.” But function in fashion is intimately entwined with aesthetics, and she believes designers and engineers have a lot to learn from one another.

While engineers understand technical potential, they know less about the wear of fabric and consumer appeal. Talent manager and founder of Fashion Tech Forum, Karen Harvey, expects hybrid companies to employ both engineers and designers as they vie for advantage. “Technologists need to recognise that beauty matters if they want to be in fashion. And we don’t need to sacrifice one for the other,” she concludes.