Sustainability in packaging remains a bit of a riddle. Sustainable packaging is not in short supply and neither is there a lack of demand, yet it is not mainstream. It is manifest in many different materials, suited to a range of applications and popular with a broad demographic, but still not considered commercial.

The conundrum seems to be that while the industry can clearly make sustainable packaging, the market somehow cannot make packaging sustainable. So what is the stumbling block?

For Debbie Hitchen, director at global sustainability consultancy Anthesis Group, the problem is sometimes the “s” word’ itself. “The definition of ‘sustainability’ can be challenging and has potential to create conflicts,” she says. “For example, for one supply chain or client, sustainability might refer to circular-economy or carbon-emissions targets, whereas for another, chemical compliance or product standards.”

Despite popularity among millennials, with Nielsen’s global study revealing almost three out of four prepared to pay more, one thing sustainability is not is a fad. All the more reason then that traditional commercial disciplines are adopted and business benefits delivered, if strategies are to scale, argues Gilles van Nieuwenhuyzen, head of Stora Enso’s packaging division.

“Saving the environment is not a trend, but a global consensus,” he says. “However, for fully renewable packaging to replace fossil-based alternatives, it needs be as much about functionality and cost-efficiency as sustainability.

“It’s about finding that push-and-pull balance between brand owners and consumers that will be the tipping point for making renewable materials-based packages the industry standard.”

The plastic problem

That said certain packaging forms appear stubbornly resistant to sustainable change. One such hard-to-fix element, identified by Marks and Spencer packaging technologist Kevin Vyse, is plastic film. “While it is lightweight, which helps reduce carbon emissions, and plays an important role in reducing food waste by keeping food fresher for longer, it is currently difficult to recycle,” he says.

In response, M&S has committed through its sustainability strategy Plan A 2025 to assess the feasibility of making all its plastic packaging from one polymer group, which would help maximise use of recycled content.

M&S is also striving to tackle complexity by making its packaging as easy as possible for customers to recycle. This represents a prime industry opportunity, says Dr Richard Peagam, associate director at Anthesis Group. “Simplification is a key area where quick wins could be made across all packaging, for example through removal of sleeves from plastic drinks bottles to make recyclability easier or considering material choices for cap lids and closures,” he says.

It is not all about waste, however. Cutting carbon is key for corporates and brands, with indirect impacts on logistics as important as direct energy usage or footprints for production, explains Mr Vyse. “When we design our packaging at M&S, we look at the whole life cycle of the product, including its carbon emissions,” he says. “For example, by reducing packaging across our snacking range, we’ve saved 72 tonnes a year, which equates to 152 fewer lorries on the road in 2017.”

The rise of e-commerce is making figures for distribution even more crucial, with failure to size-optimise packaging producing alarming results, adds Mr van Nieuwenhuyzen. “It doesn’t matter that packaging is sustainable when a majority of its content is air or even worse EPS-based fillers,” he says. “A recent calculation in Sweden showed lorries transporting e-business goods carry more than 100 million litres of air in just one year.”

The temptation when looking for a tipping-point gamechanger is to pin hopes on some transformative tech or miracle material. In the race towards more sustainable packaging, bioplastics are the longer-odds horse with the most backers.

For fully renewable packaging to replace fossil-based alternatives, it needs be as much about functionality and cost-efficiency as sustainability

According to market data from European Bioplastics, global production capacity is forecast to grow by 50 per cent, from around 4.2 million tonnes in 2016 to 6.1 million tonnes in 2021.

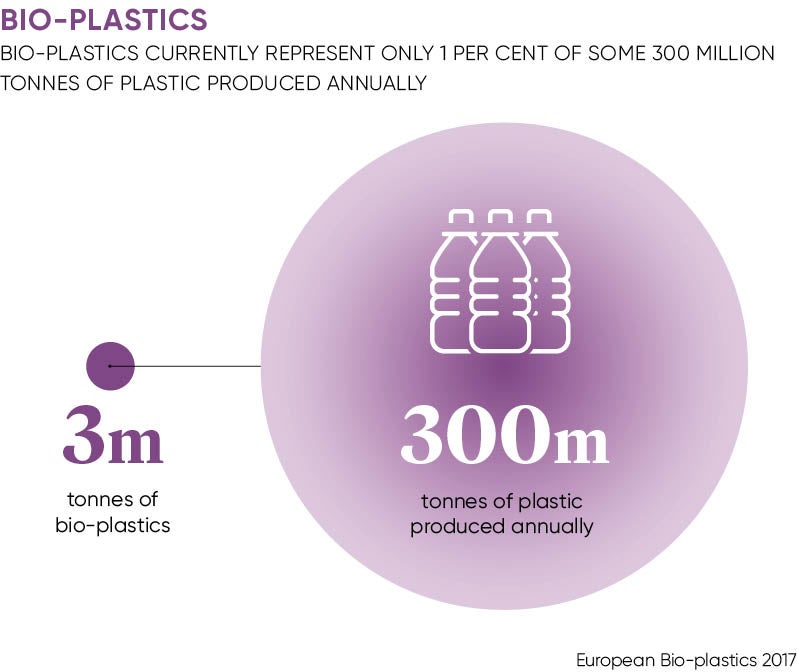

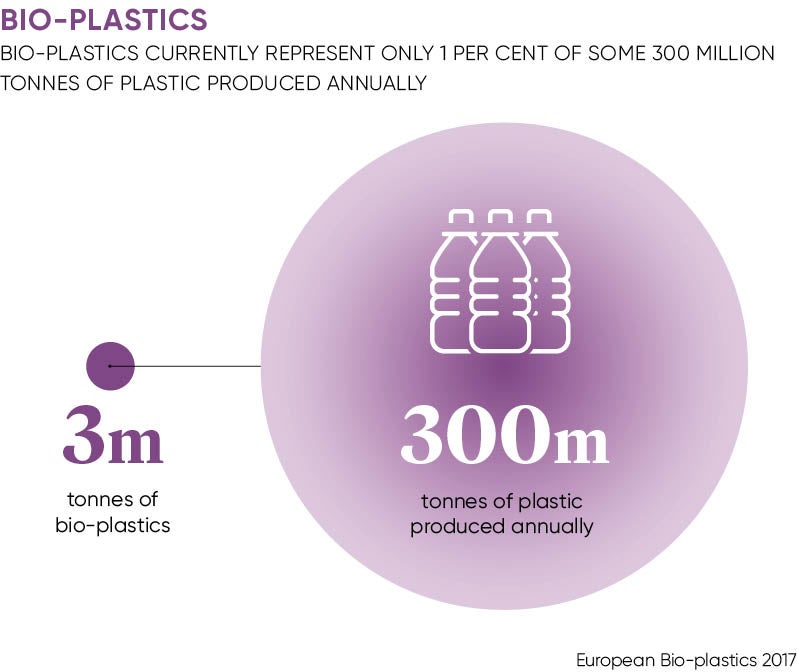

To put those figures in perspective, however, despite rising demand, bioplastics currently represent only about 1 per cent of some 300 million tonnes of plastic produced annually. Low oil prices have made it harder for suppliers to compete and concerns persist around use of agricultural land for non-food crops.

Reusable solutions

In the waste and resource hierarchy, of course, reusable solutions score even better than renewable or recyclable. Relatively slow take-up is therefore a source of frustration for pioneers such as Ross Thornley, founder and creator of Mug for Life, for whom legislation offers the best bet.

“For nearly a decade we have been actively championing the adoption of reusable coffee cups, but the infrastructure is still too complex and fragmented,” he says. “Without regulatory changes, such as happened with plastic bags, it will remain in silos with the percentage of society who are both well informed and personally compelled to seek a better solution.”

In the meantime, Mug for Life has made giant leaps forward through partnership with a key global supply chain player, getting stocked in 27 universities, plus success with bespoke versions for clients ranging from the Church of England to BT.

Ultimately, though, Mr Thornley sees mainstreaming as less about materials and more about mindsets, from supply chain decision-making to consumer naivety and disconnect. “Gaining behavioural change is a complex dynamic,” he says. “While a few see the value in adopting a more sustainable approach, habit and, honestly, convenience are still preventing a mass shift.”

For the future of packaging, it is just possible the answer to the sustainability riddle is in fact not procurement or process, but people, both professionally and personally – it’s you and me.