Cancer. A word so full of dread that it has to be mouthed or whispered. A super-foe, cloaked in mystery and armed with lethal intent.

Science and medicine have been grappling with its malevolent complexities for generations and huge advances in genetic knowledge have brought significant victories that deliver cancer-free, extended lives.

Breast cancer has five-year survival rates that have improved by 34 per cent in just 40 years. An arsenal of pharmaceutical firepower, molecular manipulation, scientific innovation and reservoirs of patient data are turning the tide against other malignancies and the word “cure” is shouted across the cancer landscape.

But, despite evident progress, cancer rates in the UK are still rising and many experts believe our approach, in some cases, needs to be refocused on controlling as well as curing disease. And, better still, preventing it.

It is hard not to be inspired by cancer survivor stories or to feel uplifted by the research driving novel therapies. But that hope is tempered by the knowledge that the 1,578 drugs licensed to target diseases cover only 3.5 per cent of the 20,000 human proteins that could harbour defective elements which could trigger cancer, according to one study. The research, by the National Cancer Institute and US Food and Drug Administration, found huge swathes of human biology yet to be targeted.

Combating cancer is multi-faceted with social and economic factors as important as scientific discovery and medical application. Early detection from better diagnostics and monitoring can be as impactful as a eureka moment in the laboratory.

Venerating the pursuit of cures can destabilise the public perception of cancer survival, says Professor Steven Miles at the University of Minnesota’s Center for Bioethics.

“This kind of reckless hype has long been repeated and long been discredited,” he says. “Cancer is not one disease. It is a vast archipelago of different diseases. In this respect, it is like infectious disease. One might find a cure for a particular infectious disease, but the proposal that we are on the cusp of curing all infectious diseases for all time is untenable.”

Professor Mel Greaves, director of the Centre for Evolution and Cancer at the Institute of Cancer Research, London, is equally forthright, advocating for a fresh perspective where living with cancer can provide extra years and a quality of life beyond incremental gains from drug discovery.

“Maybe it is more realistic to talk about finessing and restraining cancer; the more modest objective of keeping it under control,” he says. “Take someone who is 75 and, if you could control the disease with good quality of life for ten to fifteen years, then that is a success for me.

“The drugs regime would be less toxic, there could be a good quality of life and, although you may lose some years of life, it is effectively a cure.”

More than 250,000 people are diagnosed with cancer and 130,000 die as a result of it every year in England with an overall cost to society of £18.3 billion, according to Department of Health figures.

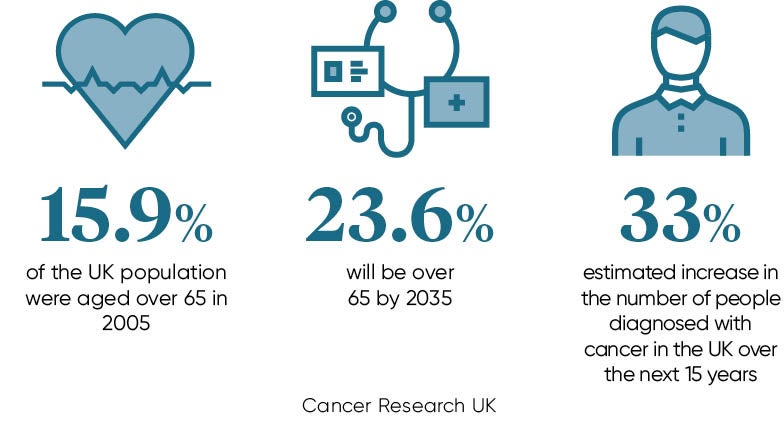

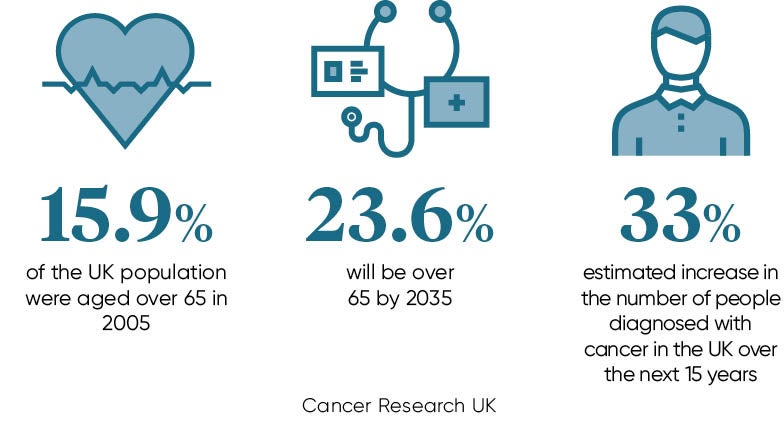

With an ageing population – the number of over-65s is predicted to reach 23.6 per cent of the population in 2035 compared to 15.9 per cent in 2005 – recently revised calculations by Cancer Research UK (CRUK) reveal that our risk of developing cancer is one in two, up from one in three.

That figure is already evident in statistics showing that the number of people diagnosed with cancer has risen by 12 per cent since the mid-1990s and CRUK predicts the rise will hit 33 per cent over the next 15 years.

“It could be that most of us will be living with cancer,” adds Professor Greaves. “The idea that you can come up with patient-specific cocktails of drugs that you keep switching is unaffordable for the NHS and it is not practicable. We need something subtler, less expensive, more manageable and less toxic.”

He highlights the treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia in adults, which corrals mutant cells so they cannot break free and cause damage around the body. It is a less complex disease than some advanced cancers, but the principle of control and restraint in place of cure has been proven.

The thrill of a laboratory discovery will never diminish and questing science needs to have full rein, but efforts at the more prosaic end of the cancer challenge, prevention, public health campaigns, the timely use of diagnostics and how to manage cancer holistically need to be factored in.

Professor Winette van der Graaf, a specialist in personalised oncology at the Institute of Cancer Research, London, believes that the life-changing success of some therapies, which have boosted survival from one year to ten within fifteen years, need to be viewed as test cases to inform the approach to combating and managing other cancers.

We should keep looking for cures, but we should not be afraid of living with cancer by managing it and keeping it under control

She is conducting a study to discover why some patients receive late diagnoses with the aim of making it easier to catch cancers earlier. “We also can learn more from the link between detailed clinical and all other data. It all starts with asking the right question and collecting the relevant data,” says Professor van der Graaf.

“The role of patients will certainly increase in the next decade. They are also taking a role in the start of research, which is a very interesting development.”

Studies have indicated that anywhere between 40 to 70 per cent of cancers are preventable. Professor Greaves adds: “New ideas about cancer evolution and drug combinations are good, and we should be actively pursuing them. But if we take our eyes off the ball on the prevention, it is a missed opportunity.

“We should keep looking for cures, but we should not be afraid of living with cancer by managing it and keeping it under control.”