Like a thief, ovarian cancer can steal a woman’s health when she is unawares. A healthy lifestyle provides little protection and the symptoms can easily be confused with those of other conditions, by patients and GPs alike.

So more than a quarter of patients are unaware they even have the cancer until they are taken to an emergency department desperately ill, by which time it may be too late for treatment to do much good. For those detected earlier, the prospects are much better as a third of women will survive for at least ten years if their disease is diagnosed in its early stages.

The best chance of improving overall survival, therefore, lies in improving awareness and early diagnosis, and developing new drugs to treat the later stages of the disease. There are signs of progress in both, but especially in treatment. “It’s very exciting for me to be working in this field,” says Dr Susana Banerjee, consultant medical oncologist at the Royal Marsden Hospital in London, where the recent advances have been pioneered.

This is a big change from the mood of “nihilism” that Annwen Jones experienced when she launched the charity Target Ovarian Cancer in 2008. “People said that the symptoms were so vague you couldn’t diagnose it earlier and there wasn’t much that could be done,” she says.

This is a disease that could be diagnosed earlier if women were aware of the symptoms and if GPs were more aware, too

“We commissioned a study to track awareness levels among women and GPs, and the experiences of women, and we repeat it every three years. We were convinced by the research that this is a disease that could be diagnosed earlier if women were aware of the symptoms and if GPs were more aware, too.”

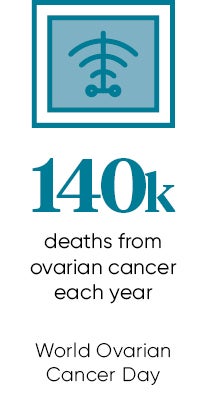

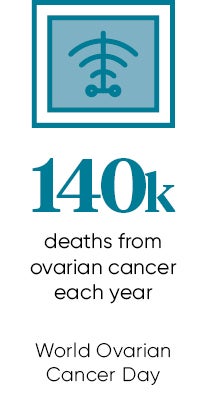

There are around 7,400 new cases of ovarian cancer every year, half in women over 65, and the numbers have remained stable since the early-1990s. There are no strong risk factors except age and family history, neither of which can be controlled. Women who have children and breast-feed themedicalm have significantly lower risks than those who remain childless. Use of the contraceptive pill also provides some protection.

There are around 7,400 new cases of ovarian cancer every year, half in women over 65, and the numbers have remained stable since the early-1990s. There are no strong risk factors except age and family history, neither of which can be controlled. Women who have children and breast-feed themedicalm have significantly lower risks than those who remain childless. Use of the contraceptive pill also provides some protection.

Around a fifth of cases have familial links, with inherited breast cancer genes BRCA1 and 2 accounting for the great majority of these. But for the rest the genetic changes that give rise to the disease are not inherited but random, striking unpredictably.

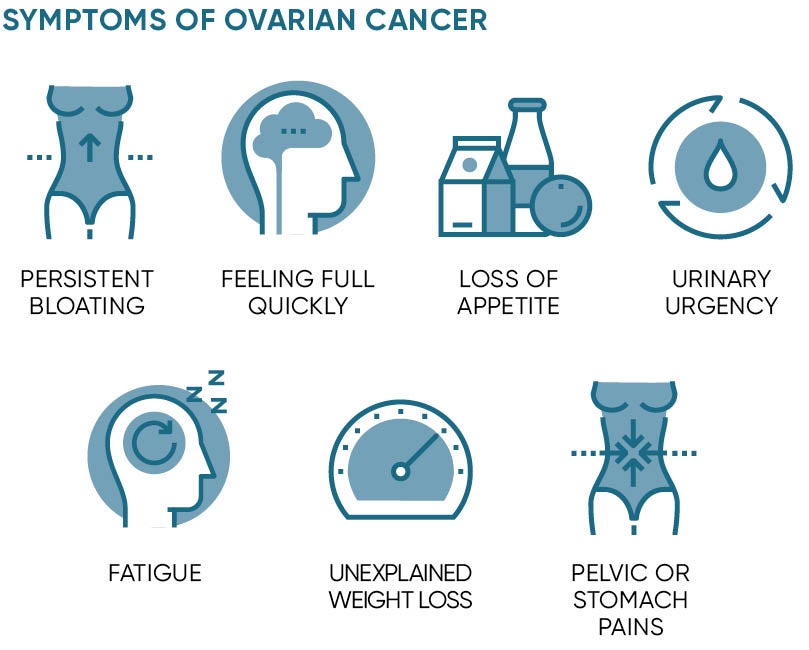

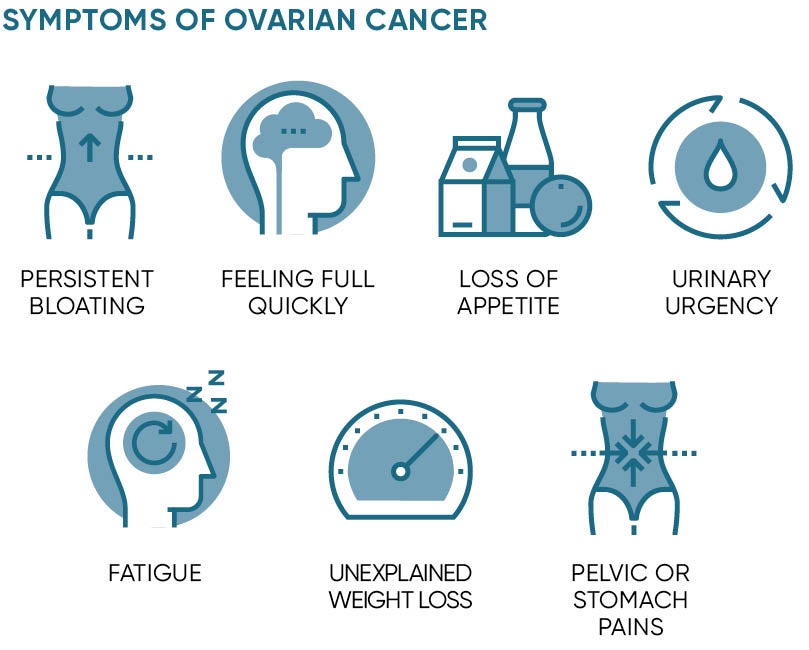

Symptoms include feeling bloated for three weeks or more, feeling full quickly or losing appetite, urinary urgency, suffering fatigue, unexplained weight loss and pelvic or stomach pains. But there are common explanations for most of these symptoms and, since a GP is unlikely to see more than one new case of ovarian cancer every five years, it is not surprising that opportunities for diagnosis are often missed.

Could more be done? Ms Jones believes so and is pressing for a national awareness campaign.

“We do local campaigns, but you need much more than that,” she says. “We really need to see ovarian cancer included in the Public Health England (PHE) Be Clear on Cancer campaign. Earlier this year, PHE ran a pilot study in the Midlands looking at awareness of abdominal symptoms, which can be linked to various cancers. We expected it to be expanded this autumn, but it seems to have ground to a halt.”

The treatment for ovarian cancer is surgery followed by chemotherapy. “For some patients, this is a cure,” says Dr Banerjee. “But for too many, the disease comes back.”

Better chemotherapy drugs such as bevacizumab (Avastin) have helped to improve outcomes. Used in combination with other drugs, it has helped to sustain a slow but steady increase in survival. But the real excitement comes from trials of a new class of drugs, the PARP inhibitors.

They work by blocking the action of an enzyme, poly-ADP ribose polymerase, which is used to repair damage to DNA when cells divide, a mechanism discovered by the Institute of Cancer Research at the Royal Marsden 12 years ago. Since cancer cells divide more often than normal ones, they are more sensitive to the effects of this damage than are healthy cells, so slowing the repair mechanism selectively attacks the cancer cells.

The first PARP inhibitor, olaparib (Lynparza), has been available in the UK for two years for women who have suffered two recurrences of the disease, while the latest, niraparib (Zejula), has just gained licensing approval from the European Medicines Agency and has yet to be certified as cost effective in the UK by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, known as NICE. Zejula is especially exciting because there is evidence that it works in women whose cancer is not caused by BRCA mutations, that is, the great majority.

“The trials show that Zejula reduces the risk of recurrence by 73 per cent in women with BRCS mutations,” says Dr Banerjee. “In practical terms that means 21 months instead of 5.5 months, on average. In women without BRCA mutations, the increase is from four to nine months.”

These are the largest benefits ever seen in survival in recurrent ovarian cancer. According to lead author of the trial, Dr Mansoor Raza Mirza, chief oncologist at Copenhagen University Hospital, these are “landmark results which could change the way we treat this disease”. Dr Banerjee hopes even better news lies ahead. “We hope we’ll be able to show this is effective earlier in the disease and will increase survival,” she says. “A trial to test this is complete and we’re waiting for the results.”