Combine unaffordable housing with increased urbanisation and single-person occupancy, as well as population growth globally, then you have a bottleneck. Constrained living spaces or micro-homes could be the answer. Architects and construction companies are now advocating so-called tiny houses under 500 square feet (46m2) as a way of solving the housing crisis, an issue that looks set to get worse.

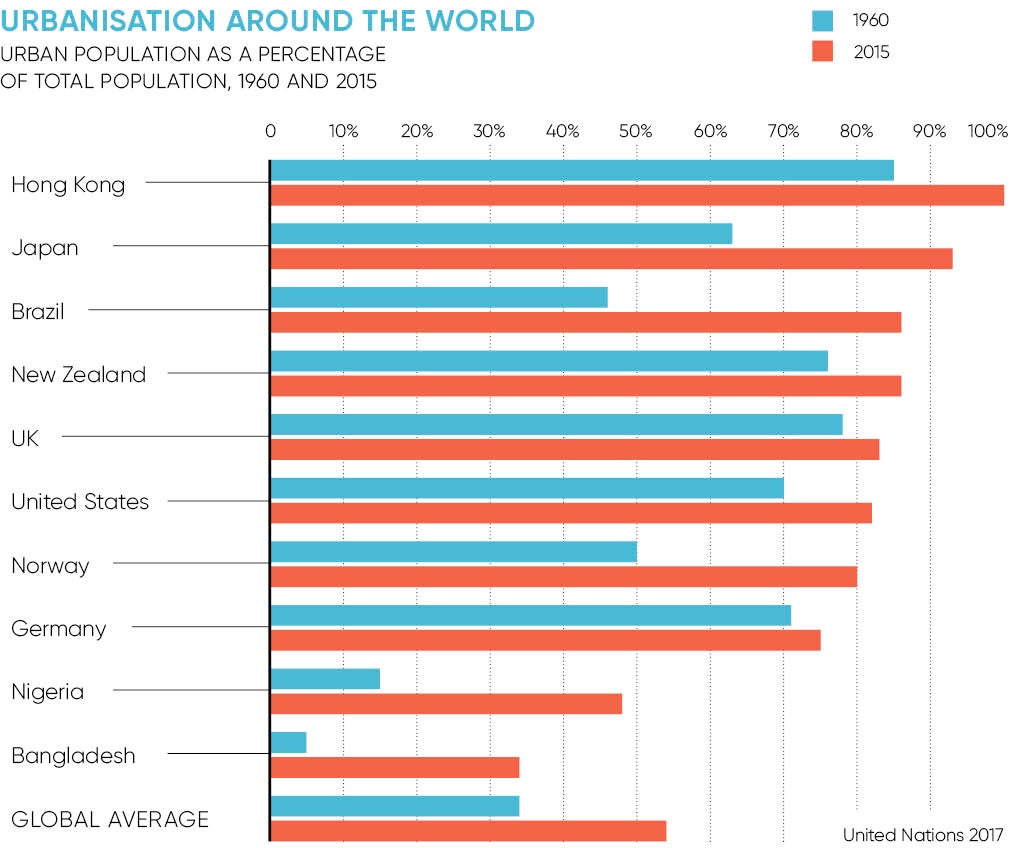

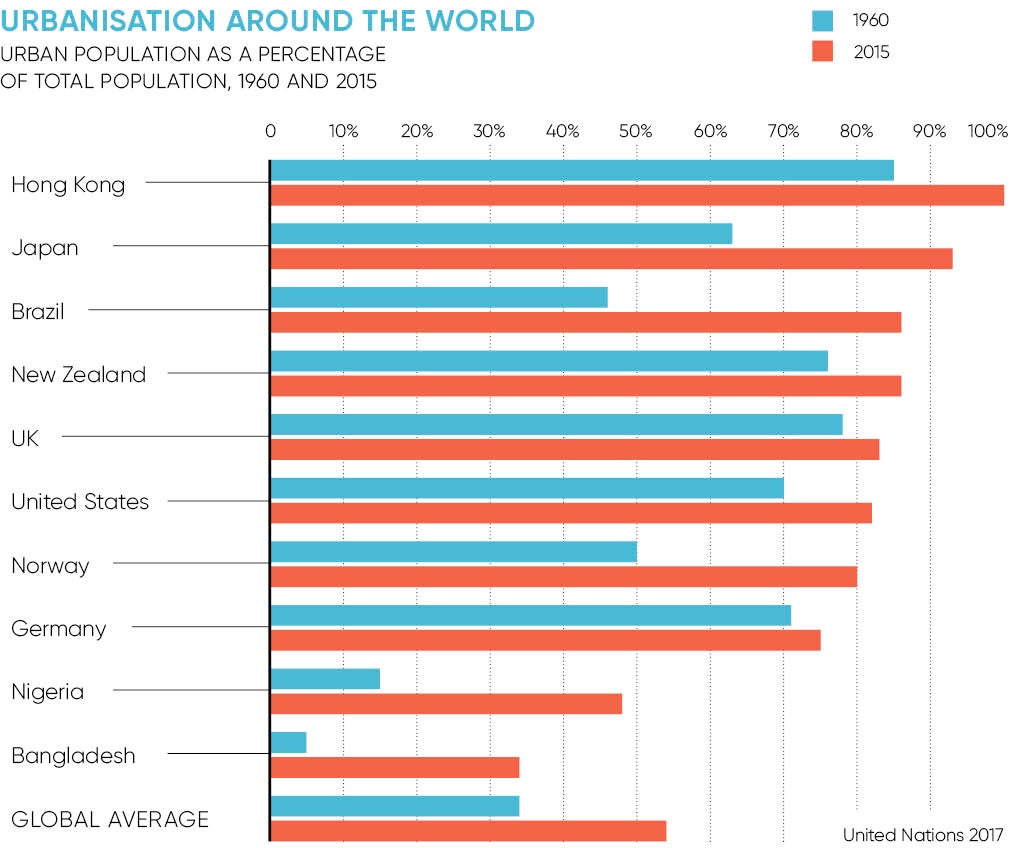

More than half the world’s population live in urban areas; by 2030 it will rise to 60 per cent, then one in every three people will live in cities with at least half a million inhabitants, according to the United Nations. By 2050 another 2.5 billion will be added to the urban masses.

It doesn’t help that London has the unenviable reputation of being the world’s least affordable city for real estate, second only to Hong Kong, says research by UBS Wealth Management. Other cities at risk of housing bubbles include Vancouver, Stockholm, Munich and Sydney.

Is mico-housing the solution?

“The fact is micro-housing built close to mass-transportation services is an easy win towards liveable, sustainable and affordable cities,” says Alex Symes, architect and founder of Big World Homes, whose company is developing one of the world’s first flat-pack homes in Australia.

“The challenge is that governments around the world are cautious to change minimum home sizes and zoning, as developers can take advantage of such planning amendments. The real issue is putting incentives into the regulations to ensure micro-housing is developed in a sustainable and affordable fashion.”

The UK is no stranger to the tiny house concept. Head to the borough of Mitcham in south-west London and you can see the Y:Cube, 36 modular, studio-like apartments only 280 square feet (26m2) in size. Made for the YMCA, they cost around £30,000 to build, off-site in a factory. Container City in the Docklands is another micro-home development made of customised shipping containers; more are planned.

With top-notch design, the construction of small homes can be an efficient use of space. They can also provide short-term solutions for cities looking to utilise plots that have yet to be zoned properly. “That way the micro-home purchaser is not having to pay full value for the land and therefore can enter the market at a lower cost,” explains Mr Symes.

The real issue is putting incentives into the regulations to ensure micro-housing is developed in a sustainable and affordable fashion

There’s also great flexibility when it comes to the use unexpected spaces. “We were approached by British Rail to see if we were interested in using land under the arches of elevated rail tracks. These spaces can be up to ten metres high – great for micro-homes,” says Quinten de Gooijer, general manager at Amsterdam-based Tempohousing.

Smaller units are also easier to prefabricate, saving time and money on each build. “We work under a controlled environment in a production hall with an efficient lay out of systems and, with no rain or snow, this increases the build quality significantly,” says Mr de Gooijer.

In the United States the drive for tiny houses has turned into a movement born out of the financial crisis a decade ago, which at the time drove Americans to seek more affordable, debt-free housing. Since then it’s flourished, with how-to websites, organisations and TV programmes.

In Europe some now see micro-homes and apartments as a move towards the sharing economy, since many normal homes are just unaffordable. “The new generations tend to move from ownership of everything to a right-of-use model,” explains Mr de Gooijer. “The housing industry will eventually undergo that same transformation – it is about offering quality living first of all and not about creating an investment for your future pension.”