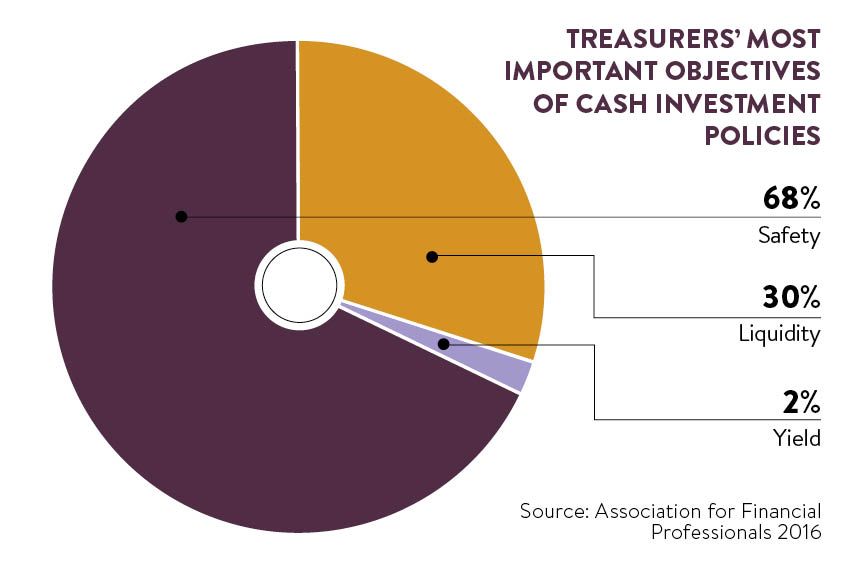

Corporate treasurers have long memories. The financial crisis of 2008 may be nearly a decade ago, but its effect is still being felt in the disposition of cash. According to a 2016 survey from the Association for Finance Professionals, the most important objective of an organisation’s cash investment policy was safety for a whopping 68 per cent of respondents; yield was the driving factor for a mere 2 per cent.

That may be partly because it’s so hard to find anything approaching a decent return. Stephen Baseby, associate policy and technical director at the Association of Corporate Treasurers, says: “We have ludicrously cheap long-term rates, but even more ludicrously low short-term rates. No one wants to hold money or to lend – people are reluctant to take a risk. Corporates have lived with the cost of carrying cash for so long, minor movements are not likely to make them change their behaviour.”

Cash-rich corporates have had a few options in their armoury for the past few years, such as notional pooling, where bank account balances are offset against each other with interest paid on the net amount, but increasing regulation is making life more challenging. Basel III – a global reform framework that has increased banks’ own funding requirements and liquidity needs – may be necessary from a global stability point of view, but has lessened the banking industry’s appetite for certain types of deposit, in particular non-operational cash.

“It’s driven a change in the behaviour of banks,” says Jennifer Doherty, global head of commercialisation, liquidity and investment products at HSBC. “The liquidity coverage ratio [which measures what types of deposits would remain on a bank’s balance sheet over a 30-day period in the event of a stress scenario] is a key measure for us and that may affect what a bank will pay for deposits.”

Asset management options

But Ms Doherty argues that bank deposits are still key to cash management for corporates. “There’s still an appetite for notice accounts, because you know where the money is, you know who the counterparty is, you know it’s safe,” she says, adding that the industry is bringing to market a raft of new products that allow banks to maintain their new liquidity ratios and still offer useful products for the corporate treasurer.

But there are different options coming through as well, according to Yann Umbricht, partner in the treasury and commodity trading group at consultants PwC. “For a company to be able to invest, someone else has to want to borrow,” he points out. “Big companies may have lots of cash, but smaller companies have either limited access to capital markets or have to finance expensive funding. It’s a great idea to put these two sides together.”

The proposition is that big corporates should help suppliers further down the food chain by paying bills more quickly, in return for a discount. Nothing new in that – discounts for early payment and factoring have long been used to improve cash flows, but now fintech companies are coming up with clever ways to automate the process through the blockchain and on a grand scale. This is discounting that requires no human intervention, but is a fully automated process.

No one ever got fired for losing a few basis points of interest, but they do get fired for losing the money

“It’s quite complicated and requires an electronic agreement that forms the basis of the discounting,” says Mr Umbricht. “You need a sufficient number of suppliers to make this work – perhaps several thousand – but we are having a lot more conversations around this concept than 18 months ago. It’s a solution that doesn’t increase your credit risk, though it does affect your working capital.”

Of course, a key element for any corporate treasurer is the need to diversify risk. “No one ever got fired for losing a few basis points of interest, but they do get fired for losing the money,” says Mr Umbricht.

Money market funds (MMFs), which typically invest in commercial paper, treasury bills and certificates of deposit, are still an option, but again legislation and regulation is limiting the appeal. In the United States, MMF reform came in this month, while the European Union’s MMF Directive, which blocks or slows redemptions in times of stress, is currently working its way through the legislative process, potentially by the end of the year.

One alternative

So with bank deposits yielding very little, MMFs losing appeal and supply chain programmes effectively restricted to the big corporates, the only real alternative are repos or repurchase agreements, according to Mr Baseby. “It’s a market that we could see develop, with corporates effectively lending to their bank or perhaps to pensions funds, which sometimes have short-term cash needs,” he says.

Mark Lewis, head of product management in corporate treasury at Bloomberg, says the pressures that have limited options have meant an increase in merger and acquisitions activity, “while more should be done to invest in the business itself, taking on more risk”. He adds: “But that seems to be the last thing businesses want to do, given the uncertainty of the outlook post-Brexit for the UK, and given stagnant growth in Europe.”

Mr Baseby agrees. “[Regulation and legislation] have created a very good environment for financial stability,” he points out, “but it is creating financial sterility.”

CASE STUDY: eBAY

Short-term liquidity at eBay used to be a labour-intensive process, with surplus cash manually moved from an operating to a savings account.

“The places to park cash and pick up favourable yield have become increasingly sparse,” says Anderson Childress, senior treasury analyst at eBay.

The company chose to implement a digital solution from HSBC, which automates the flow of cash between on and off-balance sheet investment, moving surplus cash into two pre-chosen money market funds.

“Traditionally it has been incumbent on the treasury department to manually invest surplus cash,” says HSBC’s Jennifer Doherty. “But due to increasing cash balances and shrinking investment options this has become a far more challenging task. We need to find ways to free them from the daily process of cash investment and allow them to focus on adjusting their investment policies.”

Mr Childress says: “For the first few months, we kept a close eye on our cash levels and investment, to make sure our parameters were correct and that we didn’t incur any unnecessary fees or charges. But since then we have been hands off and let it run in the background.”

The programme has freed up time for the treasury team, since analysis reports for senior management are generated automatically. Mr Childress adds: “That has enabled us to focus on more value-add strategic matters.”