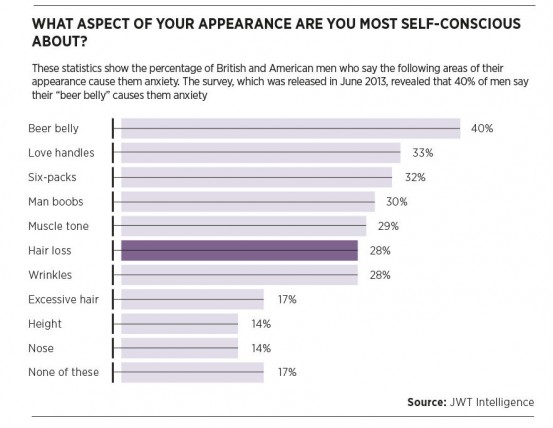

There is one aesthetic affliction that cuts to the core of all grown men - hair loss that has the power to elicit responses ranging from steadfast denial to a televangelist-style comb-over. But acceptance is increasingly inconceivable in a world where there are so many viable options to tackle follicular shortcomings.

It doesn’t take a psychotherapist to see why hair loss can break a man. For centuries, a full head of hair has been a symbol of masculinity, an expression of youth, strength and virility. For many men, hair loss is emasculating, a brutal blow to their self-esteem, a depressing reminder that time is passing.

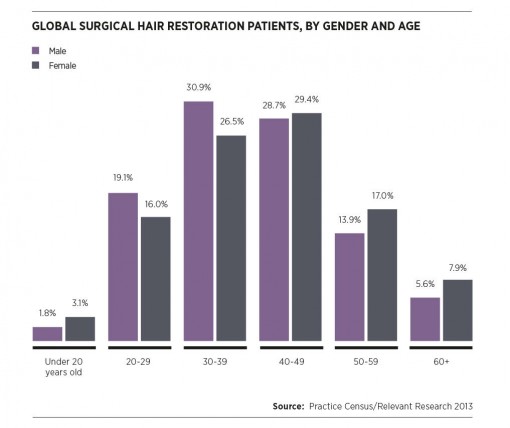

This seems doubly cruel considering that balding strikes 25 per cent of men in their 20s. Some 40 per cent will have noticeable loss by age 35, according to a study by the International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery, which also found that 47 per cent of men said they would “spend their life savings to regain a full head of hair”.

Non-invasive solutions run the gamut from plausible to preposterous. There are bulking shampoos and supplements, Travolta toupees and cosmetic camouflage, low-level lasers designed to jump start follicles, and innumerable snake oils. Market researchers Mintel report that the anti-hair-loss claim accounted for 13 per cent of new product launches in 2013, up 4 per cent on 2012.

Effective medications that slow the shedding process, such as finasteride (Propecia) or minxoidil (contained in Regaine), aren’t much help if chronic loss has already taken place. And the very idea of a strengthening shampoo is a laughable proposal for a man faced with male pattern baldness, a condition caused by dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a hormone that ruthlessly interferes with follicular activity. Transplants, therefore, are the only real option.

“Before, people used to laugh about transplants,” says surgeon Dr Bessam Farjo. “These days they’re taken seriously because people understand how natural the results are.”

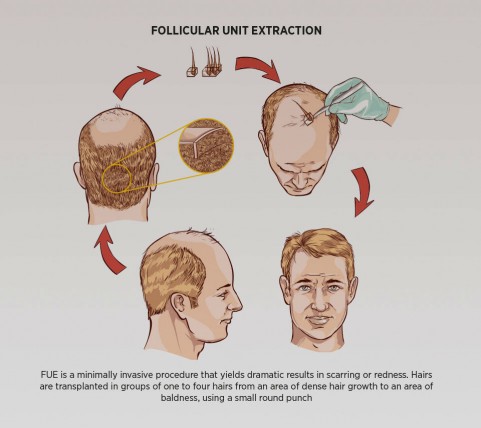

He attributes the boom in interest in celebrities, said to have benefited from hair transplants, such as footballer Wayne Rooney, former X Factor judge Louis Walsh and actor James Nesbitt, who apparently turned to follicular unit extraction (FUE), a minimally invasive procedure that yields dramatic results in a relatively short time with no shaving, scarring or redness – a quantum leap when compared to the dodgy plugs of yesteryear.

The procedure involves the extraction of individual hairs from a donor area, such as the back of the head. The grafts are then implanted one by one into balding areas, where they grow naturally over the following months. It is a painstakingly laborious process that requires a certain amount of artistry, not to mention patience, on the part of the surgeon.

There is densely packed hair in the areas that were once barren, but it doesn’t look like the patient has had any work done

“It takes a long, long time to master FUE,” says Raghu Reddy, a leading authority on the technique, whose own hair loss at age 18 defined his entire career. “It’s a lot like watchmaking – you’re sat there in an odd position, putting the pieces together for eight or nine hours a day. It’s manually intensive labour,” he says.

“What we have today is something that works; it’s based on solid science,” Dr Reddy affirms. “During my early years of performing FUE hair restoration, my average yield was between 1.9 to 2.4 hairs per graft. However, more recently my average graft yield has been 2.6 to 3.2 hairs per graft.”

Even though FUE has been around for over a decade, it wasn’t until recently that it evolved into the fool-proof phenomenon it is today. Studies now show that it is the extraction of a high-quality graft, along with the stem cells, that ensures the best results.

He pulls up a picture of a former client on the computer screen in front of us. The scalp glaring back at us has suffered extensive loss that seems impossible to reverse. The “after” picture, taken a week following the procedure, is astounding. There is densely packed hair in the areas that were once barren, but it doesn’t look like the patient has had any work done. There is no scarring, no redness.

“One could use a lot of twigs to populate the recipient area or use a few twigs and a lot of trees to create the illusion of a thicker garden,” says Dr Reddy, switching to a new analogy. This calibre of result, he maintains, is not something that would be possible to achieve with some of the other options on the market, such as follicular unit transplantation (FUT), the precursor to FUE that involves cutting out large strips of hair and leaving a scar in the process.

Dr Farjo still offers FUT, as do many other surgeons, but he maintains that either technique can yield great – that is to say “undetectable” – results “if the surgeon is skilled enough”. There are, of course, some cases where FUT is preferable to FUE, such as when a patient has a loose scalp that won’t stabilise individual grafts. “There are also some people who won’t get worthwhile coverage with FUE,” says Dr Farjo. “FUT is good for concentrated patches.”

Among his arsenal of hair loss options is the ARTAS machine, a hugely expensive robot that performs the harvesting for FUE under his guidance. “I still decide on the design process,” he says. “The difference is the robot doesn’t need to stop for lunch and it doesn’t get tired.”

Dr Reddy is less enthused with robots. “You don’t have manual control,” he says. “When grafting, you can feel a zone of resistance; there’s a tactile aid that takes years to develop.”

With so many different opinions and options for FUE – mechanical, manual, robotic and a number of marketing-driven terms that confuse matters even more – seeing the results is what will encourage a man to walk into a practice. Thanks to the proliferation of internet forums dedicated to the topic – baldgossip.com, hairtransplantnetwork.com, baldtruthtalk.com – the best and worst handiwork is immediately visible.

Doctors submit case studies to the forums, allowing viewers to do due diligence before stepping into a practice. “I’ve been working since 1993,” says Dr Farjo. “Back then nobody knew who I was; I had no reputation. By 1999 the internet had become more popular and…” he trails off. Indeed his and Dr Reddy’s names are at the top of the lists published by international forums that have thousands of subscribers.

The submission of case studies is an act that could make or break a surgeon’s career. And it has done both. But there is an upside for the consumer in such transparency. You can never hide a botch job – not with a toupee, not even in cyberspace.