The lack of policing surrounding cosmetic procedures has been a hot topic of debate for some time.

The unique way in which the market has developed means that the non-surgical sector, which is reported to account for 75 per cent of its value, sits somewhere in between the remits of beauty and medical providers.

Many of the treatments being provided are medical in nature. However, as the industry has developed in the private sector rather than NHS, the industry has evolved outside the parameters of regulation and accredited training.

This, coupled with the perceived commercial gains to be had from this booming market, has resulted in a plethora of unscrupulous providers exploiting loopholes, due to the lack of regulation, with little redress when things go wrong.

The sad truth is that, with the exception of Botox, which is a prescription-only medicine and should only be offered only by someone qualified to prescribe it, non-surgical cosmetic services may be provided by anyone, anywhere. Public confusion over who to go to for what and where has naturally ensued.

Areas of conce

Since the Keogh Review published its recommendations in 2013, and highlighted the training and qualifications of cosmetic practitioners as an area of key concern, moves have been made to address this important issue, although the majority of medically trained practitioners within the sector would argue that anything less than statutory regulation is not enough.

Most significantly, Health Education England (HEE) was commissioned by the Department of Health to compile a report aimed at improving and standardising the training available to practitioners who carry out non-surgical cosmetic procedures. Cosmetic surgery was not included in the report as this is regulated in the UK.

With the exception of Botox, non-surgical cosmetic services may be provided by anyone, anywhere

The result was a recommended education and training framework, which was published in two parts between November 2015 and January 2016.

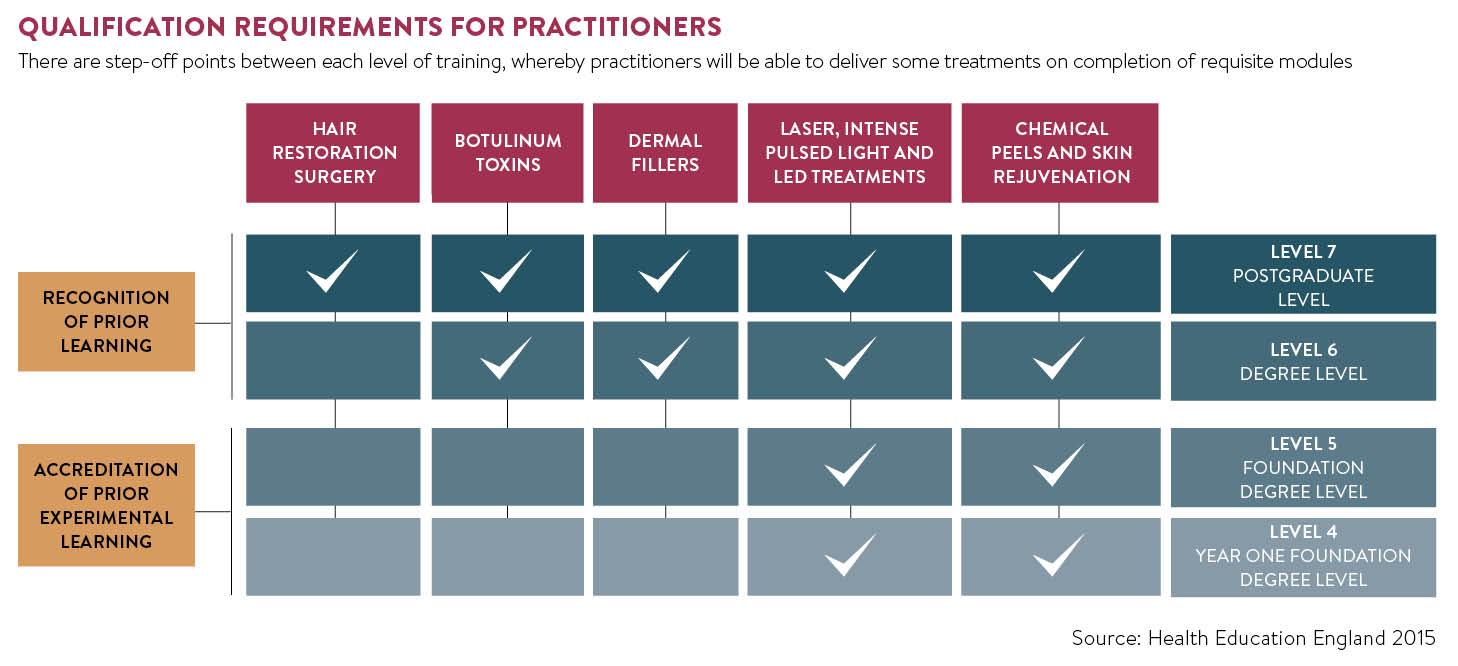

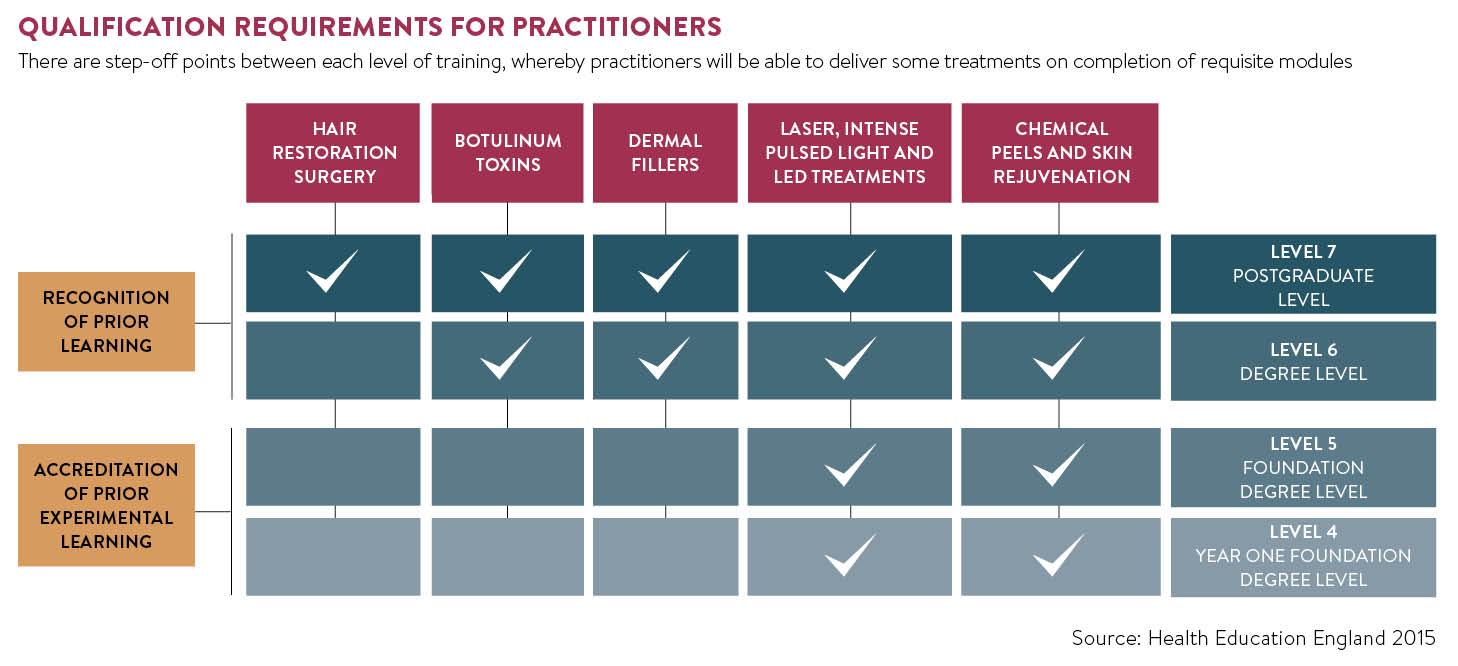

The report set out qualification requirements for practitioners who perform these types of treatments, regardless of any previous training they might have had or their professional background.

It separated commonly performed cosmetic procedures into categories based on the level of training the HEE believed those performing such treatments should have. The entry-level requirement, the report suggested, should be a vocational level-three qualification, as held by qualified beauty therapists.

Treatments such as lasers and intense pulsed light or IPL for hair removal, non-ablative lasers, IPL and LED lights for photo-rejuvenation, microneedling with needles less than 0.5mm, and superficial chemical peels, could be performed by anyone with a level-four qualification, equivalent to a foundation degree year one and above.

Treatments such as laser tattoo removal, laser and IPL treatments for benign vascular lesions and microneedling with needles between 0.5 and 1mm should only be done by those with a level-five or foundation degree-level qualification in these procedures.

Level six or degree-level qualification should be held by those performing homeopathic mesotherapy, microneedling with needles up to 1.5mm and ablative fractional laser treatments, excluding treatments around the eye.

The top tier of treatments, for which it suggested practitioners be trained to a minimum of level-seven post-graduate or masters degree, includes laser treatments around the eye, medium or deep chemical peels, hair restoration surgery, ablative laser treatments, fat-busting injections, mesotherapy with pharmaceutical strength agents and, importantly, the injection of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin.

Industry battles

The industry has long battled against non-medics and unqualified practitioners injecting dermal fillers. The British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons (BAAPS) has been lobbying for dermal fillers to be classified as prescription-only medicines, rather than medical devices, something the Keogh Review recommended, and believes they should only be administered by medical professionals who are capable of dealing with any complications, especially as many of them now include the anaesthetic lidocaine, a medicinal ingredient.

Previously this would have required Europe-wide approval, however, former BAAPS president and consultant plastic surgeon Rajiv Grover believes Brexit may offer an opportunity for the UK to reopen the debate.

The key objective is patient safety and this can only be achieved by delivering an agreed set of standards – an open and fair regulatory system

“Making dermal fillers prescription-only would achieve a ‘triple-whammy effect’. First of all, if a product is prescription-only, you can regulate what comes on to the market. Secondly, it would mean fillers could only be done by healthcare professionals and thirdly, as it is illegal to advertise a prescription-only medicine, it would automatically block inappropriate marketing,” he says.

In the absence of any formal regulation, the HEE recommendations do offer some clarification. While only recommended guidelines, they are now being used as a benchmark by industry bodies such as the British Association of Cosmetic Nurses (BACN), British College of Aesthetic Medicine (BCAM), Joint Council for Cosmetic Practitioners and General Medical Council (GMC), which are keen to see a way forward in improving patient safety.

Sharon Bennett, chairwoman of the BACN, says: “The key objective is patient safety and this can only be achieved by delivering an agreed set of standards – an open and fair regulatory system.”

Aesthetic-specific level-seven accredited training courses and masters degree university courses are also now being established across the UK to give medical practitioners a pathway to achieving the standards of training outlined by the HEE.

None of these courses are currently being offered to non-medical practitioners. However, the public should be vigilant as the lack of regulation means that courses training beauticians in dermal fillers do exist, but are not equivalent qualifications and do not reach the levels recommended in the guidelines.

On the surgical front, to address the lack of training in cosmetic surgical procedures within the NHS, BAAPS last year announced the launch of a fellowship programme. Paid for by BAAPS, with support from the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons, the fellowships offer hands-on practise, mentorship, access to specialist expertise and understanding of how to deal with complications.

Staying safe

While the HEE guidelines may give some clarification on who should be doing what and appropriate levels of training, their implementation is still in its infancy. So what can the public do to safeguard themselves from rouge practitioners in the here and now?

If you are considering a cosmetic procedure you should always check the practitioner’s credentials. For surgical procedures seek a plastic surgeon who is on the specialist register of the GMC and look at the BAAPS website for a surgeon specialising in the specific procedure you’re seeking.

In England, clinics and hospitals that deliver private cosmetic surgery procedures must also be registered and inspected by the Care Quality Commission. Check a clinic’s certification and read inspection reports.

Only registered doctors, dentists, prescribing nurses and prescribing pharmacists are able to prescribe botulinum toxin legally and should, therefore, be the only practitioners offering treatment. You should check that they are registered and accountable to a statutory body, such as the GMC, Nursing and Midwifery Council or General Dental Council.

While this doesn’t guarantee that they have adequate training in aesthetic procedures it does mean they are accountable to their professional body and you are guaranteed a right of redress if anything goes wrong. If their code of conduct is broken, practitioners can lose the right to practise. Also look for medical practitioners who are members of BCAM or nurses registered with the BACN.

Other procedures, such as laser hair removal, skin peels and non-invasive body contouring treatments, may be performed by a trained beauty therapist, although many in the aesthetic sector feel that laser treatment, which was previously deregulated, should be brought back under regulation, due to the high risk factor for serious burns when the treatment is administered by people without appropriate qualification.

In the future we may see further clarification and, if lobbying by BAAPS is successful, the classification of dermal fillers as prescription-only medicines. In the meantime, the best way to ensure you don’t fall victim to unscrupulous practice is to do your research, and then check and check again.

Areas of conce