Despite continuing to grow year on year, the cosmetic procedures market, encompassing cosmetic surgery and non-surgical aesthetic procedures, has been constantly rocked by negative headlines of unscrupulous practice and treatments gone wrong.

Often described as a regularity minefield, the terms “cosmetic cowboy”, “botched” and “bogus” are used with alarming regularity when referring to both surgical and non-surgical treatments.

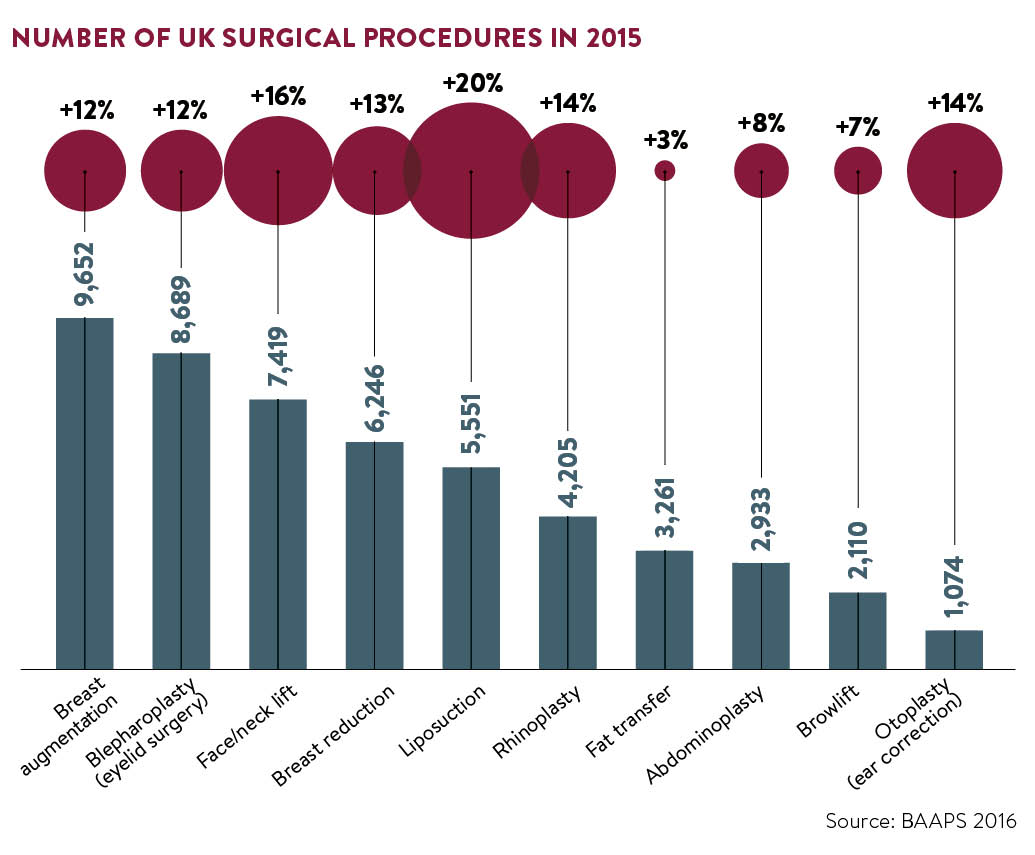

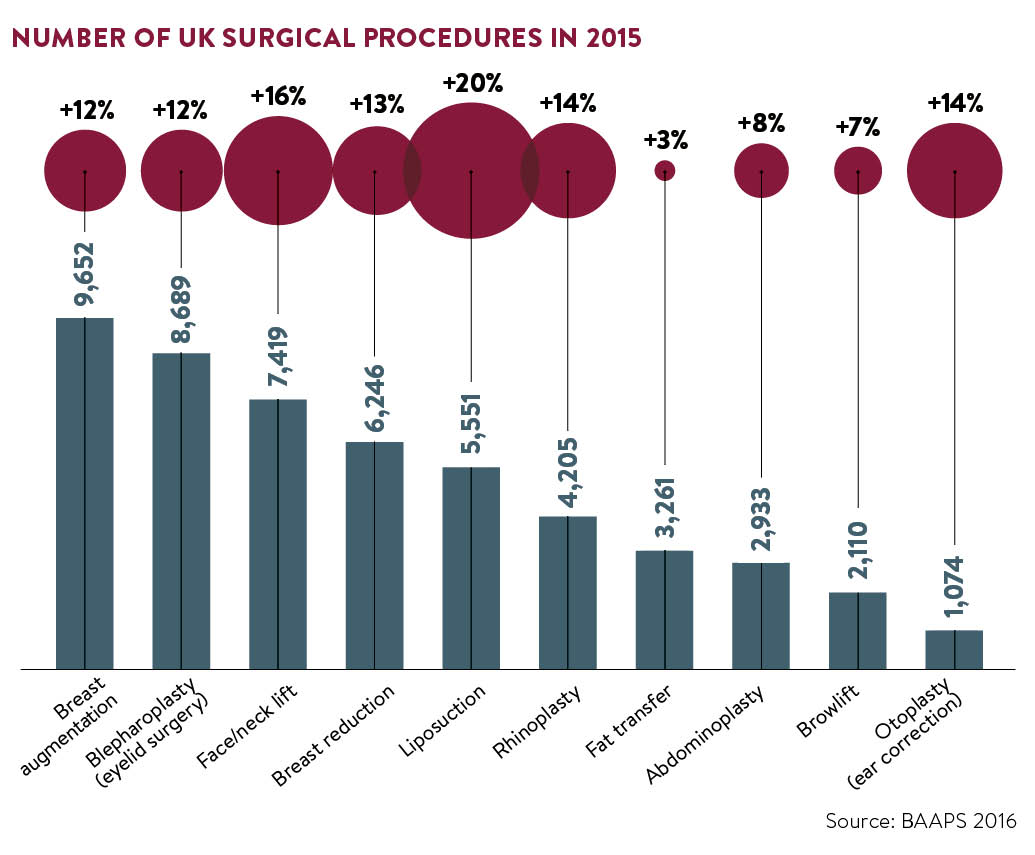

It may seem ironic then that recent statistics have shown exponential growth in the sector. The global facial aesthetics market is expected to exceed £3.8 billion by 2020, according to a report by Technavio, while the British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons (BAAPS) reported a record number of Brits (51,140) underwent surgery in 2015, a double-digit rise.

But why has the trend for cosmetic enhancement continued to boom despite the negative press and lack of regulation? The truth is that the headlines only reflect a snapshot of an industry that is, for the most part, operating to high ethical standards.

So, what is the current situation when it comes to regulation in the UK? Following the PIP breast implant scandal in 2011, the government commissioned Professor Sir Bruce Keogh, national medical director at NHS England, to spearhead a review into cosmetic interventions in England in a bid to tighten up standards.

The Keogh Review highlighted a number of areas of concern, including unethical marketing practices, widespread use of misleading advertising, lack of training and unsafe practices, and made a number of recommendations to improve clinical practice and safety. Patient safety, it said, must be a priority.

However, despite the report’s recommendations, the government decided against statutory regulation and the industry was left to police itself.

What has changed?

Three years on and reports about botched procedures don’t seem to have slowed down. The #SafetyInBeauty campaign reported a record year of complaints in 2015 and BAAPS said two out of three surgeons had seen patients suffering complications from dermal fillers. However, it’s not all doom and gloom. While critics would have us believe that nothing has changed since the Keogh Review, in reality some positive steps are being taken to safeguard patients.

This year saw the first statutory regulation in the UK come into force in Scotland. From April 2016, all practitioners carrying out non-surgical cosmetic interventions, such as botulinum toxin, dermal fillers and teeth whitening, are subject to checks by government-approved body Healthcare Improvement Scotland. Those not conforming could face consequences from as early as 2017.

In England the situation is somewhat different, however, and a number of different steps are being taken in a bid to take control of the situation.

[embed_related]

One of the areas highlighted by Keogh was training and Health Education England (HEE) was commissioned to examine standards, publishing its recommendations for a framework of formal education for those providing aesthetic treatments earlier this year. While this is not a legal requirement, it may go some way towards clarifying the levels of qualifications those providing non-surgical treatments should have.

A Joint Council for Cosmetic Practitioners (JCCP) and Clinical Standards Authority for Non-Surgical Cosmetic Interventions (CSA) have also been established. The CSA has been tasked with delivering a definitive set of clinical and practice standards based on a review of current practice and the work previously undertaken by the HEE. The JCCP, which aims to launch in April 2017, sees five key industry bodies – the British Association of Cosmetic Nurses, the British College of Aesthetic Medicine, the British Association of Dermatologists, the British Association of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons and BAAPS – working together to take these initiatives forward.

New standards

Another positive move came in June when the General Medical Council (GMC) introduced new standards for doctors carrying out cosmetic procedures. The guidance says doctors must advertise and market services responsibly; give patients time for reflection; seek a patient’s consent themselves, not delegate it; provide continuity of care and support patient safety by making full and accurate records of consultations and contributing to programmes to monitor quality and outcomes, including registers for devices such as breast implants. It also warns against the use of promotional tactics, such as “two-for-one” offers and bans the practice of offering procedures as prizes.

The Royal College of Surgeons has also published its own set of professional standards, specifically for cosmetic surgery, which will supplement the GMC’s guidance and later this year will launch a new certification scheme, allowing patients to search more easily for a surgeon who has the necessary skills and experience to perform the procedure they are considering.

In addition, the GMC has published a guide for patients considering cosmetic procedures, which gives advice and information on things to take into account and the questions they should ask their doctor.

June also saw the introduction of a new Cosmetic Redress Scheme, designed to resolve complaints made by consumers against traders in the cosmetic, aesthetic and beauty sectors. This came as a result of new legislation introduced in October 2015 that requires all traders to signpost consumers to a government-authorised consumer redress scheme.

Initiatives have been established with the ultimate goal of safeguarding the public from rogue practitioners

In July, Save Face, a commercially funded register established in 2014, was accredited by the Professional Standards Authority for Health and Social Care (PSA). The register is voluntary and practitioners who sign up can display a logo to show they have complied with certain criteria. However, it is not a government-backed regulator and concerns have been raised over it being a for-profit organisation.

Treatments You Can Trust offers a register of injectable cosmetic providers and is accredited by the PSA.

All these initiatives have been established with the ultimate goal of safeguarding the public from rogue practitioners. But while the industry does its part those seeking treatment also have a role to play.

The challenge now is public education and making sure those wanting cosmetic procedures are seeking them from the right people and making well-informed, safe choices.