When the charity Médecins Sans Frontières was asked to investigate severe and unusual symptoms – protruding tongue, extended neck, facial cramps and contorted upper body – among hundreds of patients in the Democratic Republic of Congo, doctors were puzzled. But they discovered the patients had all taken fake Diazepam to “treat” a wide range of illnesses, including malaria.

Diazepam is usually used to treat anxiety disorders, alcohol withdrawal and muscle spasms. Occasionally doctors use it to try to control convulsions in people with malaria, if there is no alternative. The shortage of medicines and poor access to health facilities in this remote part of Africa meant it had been used as a last resort. But it had been falsified.

Laboratory analysis showed the tablets contained no Diazepam at all, but instead between 10mg and 20mg per tablet of haloperidol, an anti-psychotic that is used primarily to treat schizophrenia. One of the known side effects is severe and uncontrollable muscle spasms in the face and neck.

These patients recovered. Many people who take or use falsified or substandard medicines or medical products are not so lucky. It is estimated that fake malaria drugs kill more than 100,000 children in Africa each year. Fake emergency contraception has led to a rise in dangerous abortions in East Africa. Four people died and seven suffered brain damage in Singapore after taking counterfeit drugs to treat erectile dysfunction. And the list goes on.

Thousands of people die or suffer lasting damage every day as a result of using falsified treatments for everything from weight loss and wrinkles to organ transplant, cancer and diabetes.

The culprits

Mick Deats, group leader at the World Health Organization (WHO) on substandard and falsified medical products, says the clandestine nature of counterfeit medicine manufacture makes it difficult both to track down the perpetrators and quantify the extent of the problem.

“There is no audit trail because most purchases are made in cash,” he says. “In the fake Diazepam case, the most likely explanation was that someone was trying to get rid of a batch of tablets that were approaching their expiry date. But we see this kind of thing every day.”

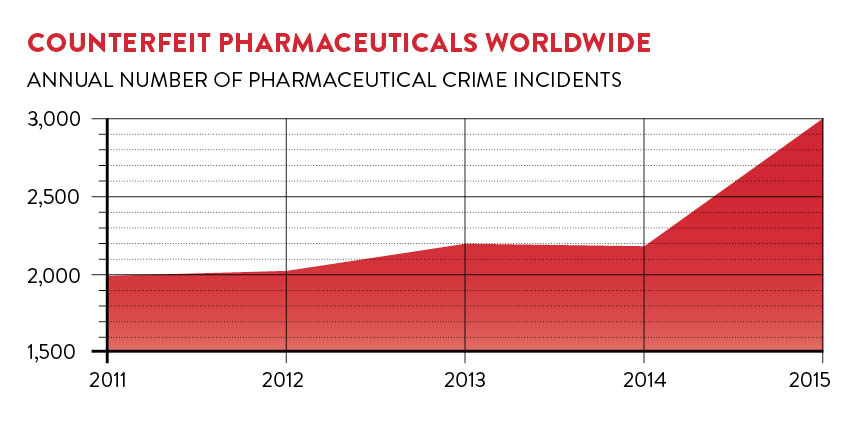

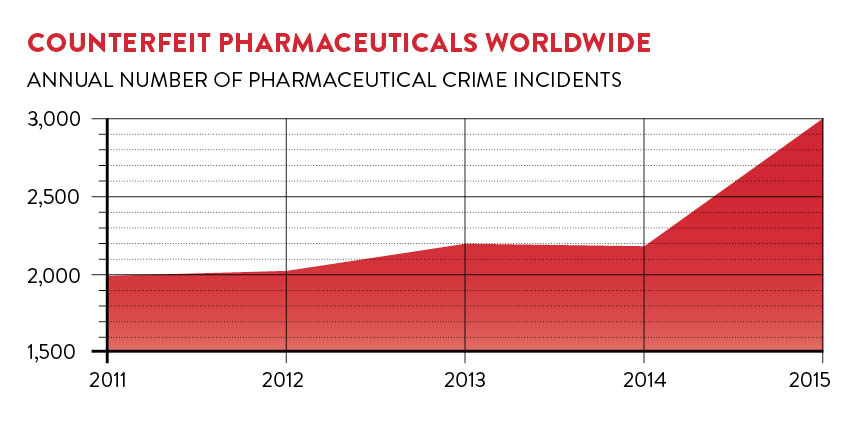

The problem is big – up to 15 per cent of all drugs sold worldwide are estimated to be fake – and it’s growing. But it’s not new. Paul Newton, a professor of tropical medicine and director of the clinical tropical medicine research group, the Lao-Oxford-Mahosot Hospital-Wellcome Trust Research Unit, based in Laos, says: “Poor quality drugs have been a persistent problem for hundreds of years. In the 1600s fake cinchona bark and in the 1800s fake quinine, both malaria treatments, were a problem.”

The enormous growth in the medicines manufacturing industry over recent years has been accompanied by a commensurate rise in falsified and substandard products. And because countries such as China and India are among the biggest manufacturers, “you would expect the number of falsified drugs they produce to have risen accordingly”, says Professor Newton. “Regulation in non-wealthy countries, however, hasn’t kept pace. So while we do see occurrences of falsified products in Europe, Australia and the United States, they are relatively low.”

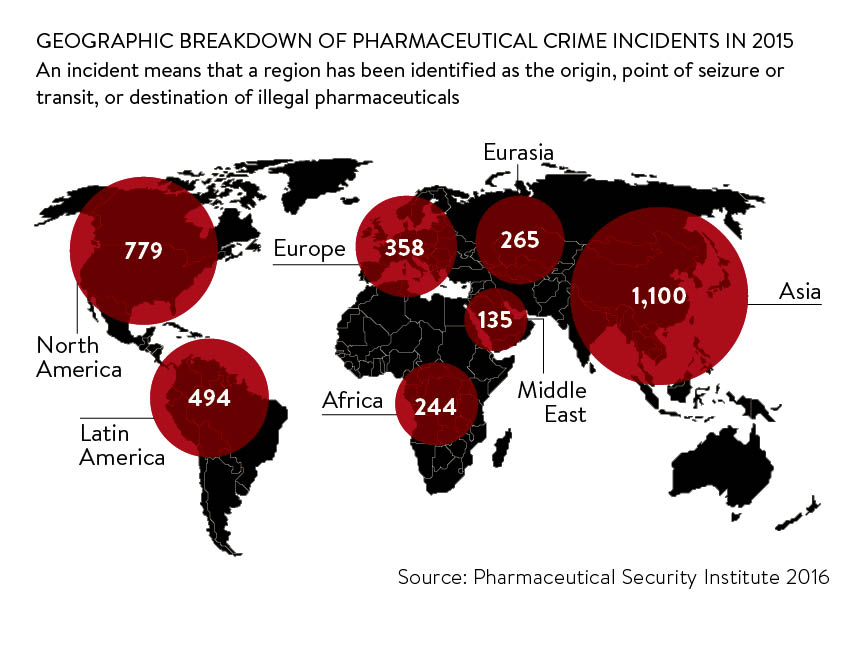

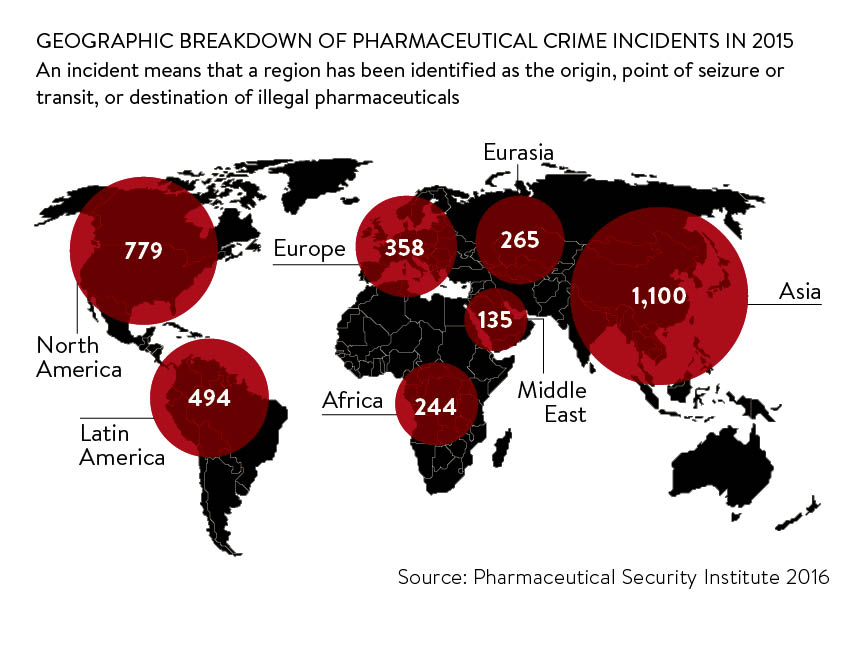

But figures from the Pharmaceutical Security Industry (PSI), a US-based not-for-profit membership organisation dedicated to protecting public health, sharing information on counterfeit drugs and initiating enforcement action, suggest that no country is immune to counterfeiting. In 2015 the PSI found that while 1,100 incidents were reported in Asia, there were 779 in North America and 358 in Europe. An incident means that a country has been identified as the origin, point of seizure or transit, or destination of illegal pharmaceuticals.

Impact on business

And while the public health implications are huge, manufacturers as well as tax authorities also suffer. Some frequently cited statistics include the worldwide value of counterfeited medicines being around $75 billion, according to the US Center for Medicine in the Public Interest, and a World Economic Forum estimate in 2011 that the impact on drugs manufacturers was around $200 billion.

More recently, the European Union Intellectual Property Office estimated that the EU pharmaceutical sector loses €10.2 billion a year, or 4.4 per cent of sales, to counterfeit medicine. But intellectual property law expert Iain Connor of Pinsent Masons says: “The value is at least ten, if not 100, times bigger than the reported figure.”

Developing countries are an obvious target for counterfeiters because legitimate drugs may be too expensive for most people and legal controls are weak. But higher-income countries, despite their stringent regulations and better law enforcement, offer high rewards in exchange for relatively low risk.

Around half the medicines sold online are fake or unlicensed

Regulation has to improve, not only to protect public health, but also to protect the reputations of legitimate manufacturers of both innovative and generic products, says Professor Newton. But manufacturers themselves could do more.

“If a genuine manufacturer has a product falsified, of course that will damage its reputation, so it will be understandably nervous about reporting it,” says WHO’s Mr Deats. “But that is a very short-term view.”

Companies have to strike a difficult balance between demonstrating they are taking action to protect their drugs and not frightening people off taking them, and it’s a dilemma that is replicated in public health too. “We all need to work harder on the communication aspects of this,” says Professor Newton.

What’s being done?

The message is not lost on the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). It recently launched a public health campaign FakeMeds aimed at educating 18 to 30 year olds, the group most likely to buy medical products online, about the dangers of doing so.

As regulation and detection of counterfeiting improves, thanks to initiatives such as the global monitoring system WHO Rapid Alert, criminals are shifting their activity on to the unregulated internet. Around half the medicines sold online are fake or unlicensed.

The MHRA is currently focusing on diet pills. Since 2013 it has seized nearly one million fake or unlicensed slimming products, which contain dangerous or banned ingredients that can cause serious side effects or death. Next year it will shift its focus to condoms and sexually transmitted infections kits.

The problem of fake medicines will only be solved by what Mr Deats describes as a “prevention-first, co-ordinated multi-stakeholder response to the problem”.

Measures mandated in the European Commission’s Falsified Medicines Directive will help. For example, manufacturers will have to apply safety features to packaging, including a tamper-proof security seal and a two-dimensional barcode that pharmacists will scan to authenticate the medicine.

The new requirements are creating good business for anti-counterfeiting and brand protection technology companies such as Holoptica. UK managing director David Niven says: “Holograms used to be the classic way a brand would protect itself, but now holograms are counterfeited too and very few people would be able to distinguish between a real one and a counterfeit.”

Holoptica incorporates a range of non-counterfeitable security elements into its holograms, including QR codes, near-field communication technology, DNA markers and microdots. It is also developing ingestible DNA to protect the medicines themselves. All its products incorporate a track-and-trace element to enable manufacturers to keep tabs on their products throughout the supply chain.

A few years ago, Mr Deats, who was head of enforcement at the MHRA, was instrumental in foiling a plot to get fake medicines from China into the NHS. He believes the high-profile arrests of the perpetrators have done much to deter others.

But Professor Newton describes medicine falsification as “the world’s third oldest profession” and believes, like prostitution and spying, it will never be eradicated. “We will always be at risk, but the risk is higher in some places than others,” he concludes.

The culprits

Impact on business