Angola launched its first steel mill in December 2015. Its owner, Georges Choucair, a French trader-turned industrialist, proudly showed a huge delegation of government officials and local dignitaries through its cavernous halls and out to where its raw materials were piled, huge rusting dunes of scrapped train carriages and the carcasses of tanks left over from the country’s civil war.

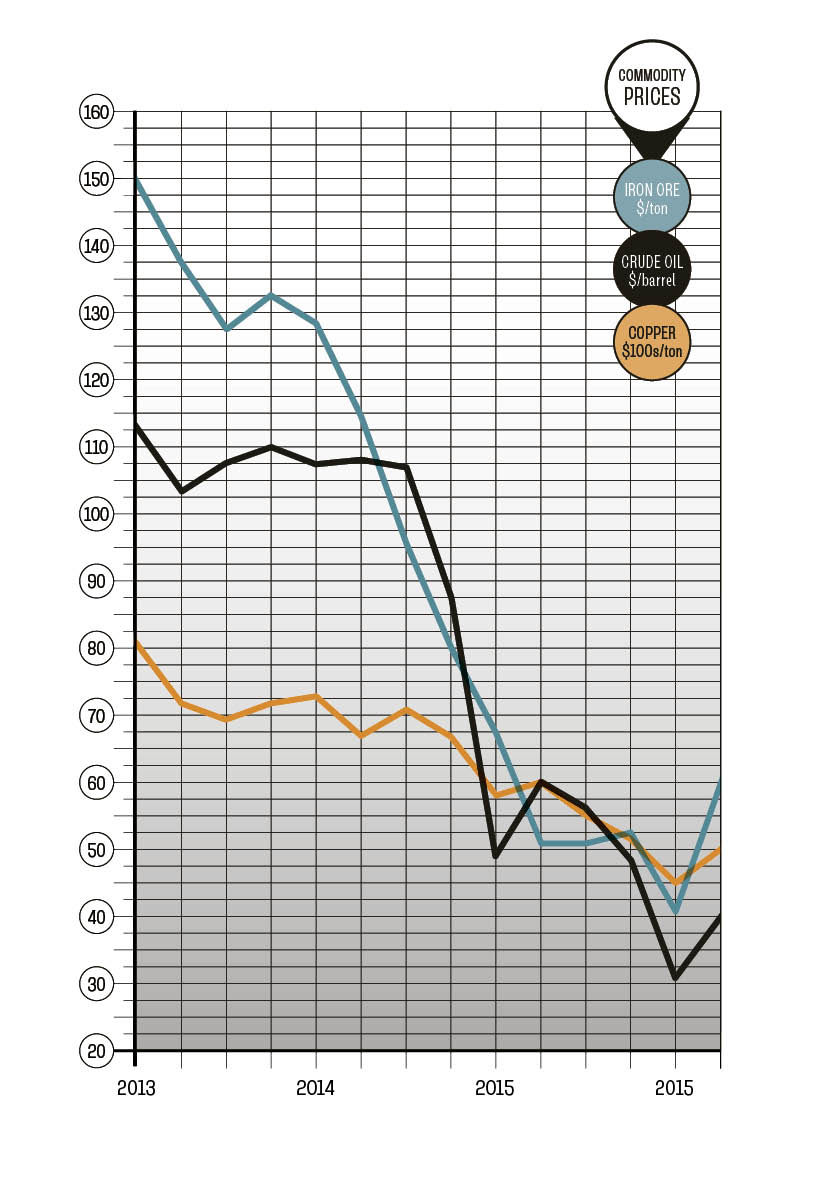

Choucair raised $300 million (£210 million) for the facility, which could supply the entire country’s demand for steel rebar. Even as the first bars were cooling on the factory floor, the venture seemed beyond quixotic. Angola’s petro-economy was in freefall after 18 months of low oil prices, and worse, mills all around the world were shutting down, battered by low demand and a glut of Chinese-made steel on the market, supported by huge subsidies from the government in Beijing.

On the sidelines of the launch, a European engineer, brought in to help build the plant, gave a resigned shrug. “It’s a good mill,” he said. “But in the end, no one can compete with the Chinese price.”

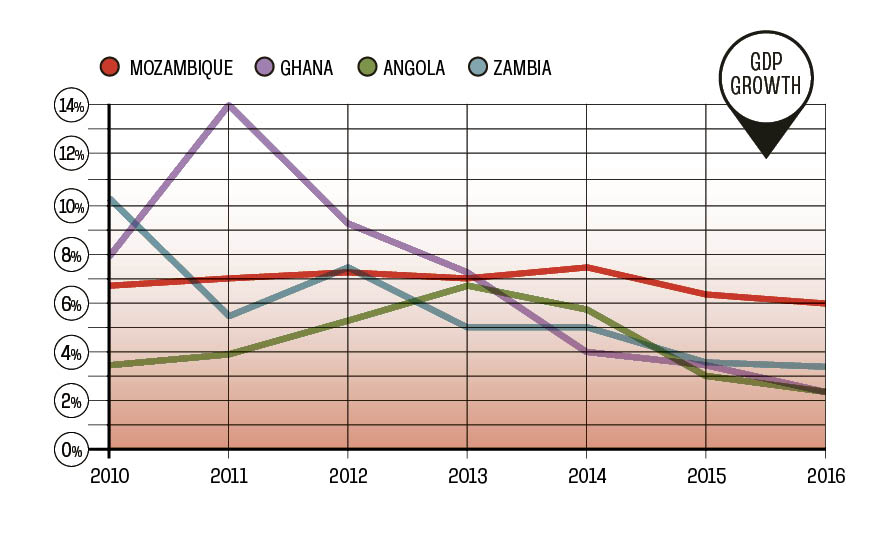

Angola, which vies with Nigeria for the dubious honour of being Sub-Saharan Africa’s largest oil exporter, was one of the stars of the 21st Century narrative of ‘Africa Rising’, a dramatic — and not entirely fictional — leap forward in economic growth and political progress that seemed to have untied them from the dark days of the 1990s. Although there is wide variation in the 54 countries of Africa, that growth was driven by a combination of improving political stability, demographic growth and, most importantly, the commodity ‘super-cycle’ of abnormally high prices for natural resources.

China’s economic development and desire for geopolitical influence had a profound impact too. First, government loans and grants, often in exchange for natural resources, helped to build sorely underdeveloped infrastructure; then investment by Chinese private companies, creating an entirely new competitive landscape for businesses on the continent.

Angola was an archetype of this trend. Its annual gross domestic product growth was routinely in double figures in the mid-2000s. The end of its civil war meant that its large offshore oil fields came back onstream at the right moment to catch the upswing in oil prices that topped out at $145 per barrel in 2008. The country generated billions of dollars in revenue. China was a major partner.

The slump in the oil price, now two years in, pulled the bottom out from Angola’s government budget, 90 per cent of which is derived from oil. Angola’s fiscal ‘breakeven’ price — the point at which it actually generates a surplus from its oil production — is $77 per barrel, due to a combination of its dependence on the commodity and the high cost of extraction from its deep offshore fields.

The immediate implications of that sudden loss of revenue have been profound. The national budget has been slashed, removing social safety nets that have contributed to a building public health crisis, following a yellow fever outbreak. Public sector wages have gone unpaid, which locals say has led to a rise in official corruption. On a recent visit to Luanda, Raconteur witnessed immigration officials accepting money to waive the rule insisting that entrants have a valid yellow fever vaccination certificate, as well as routine demands for small facilitation payments by police.

The downturn has also exposed the fragility of its rentier economy, which allowed it to spend on public projects in lieu of generating jobs. The African Development Bank estimates that unemployment is around 26 per cent, although unofficial estimates suggest that the rate is far higher, and many of the jobs that do exist are in the informal sector.

Income inequality is among the highest in the world. From the high balconies of Luanda’s central cluster of skyscrapers, the city still has a jagged skyline of half-finished buildings and cranes; a few kilometres outside the business district, the paved road crumbles away. As one local businessman says: “This is a city that only looks good from above and at night.”

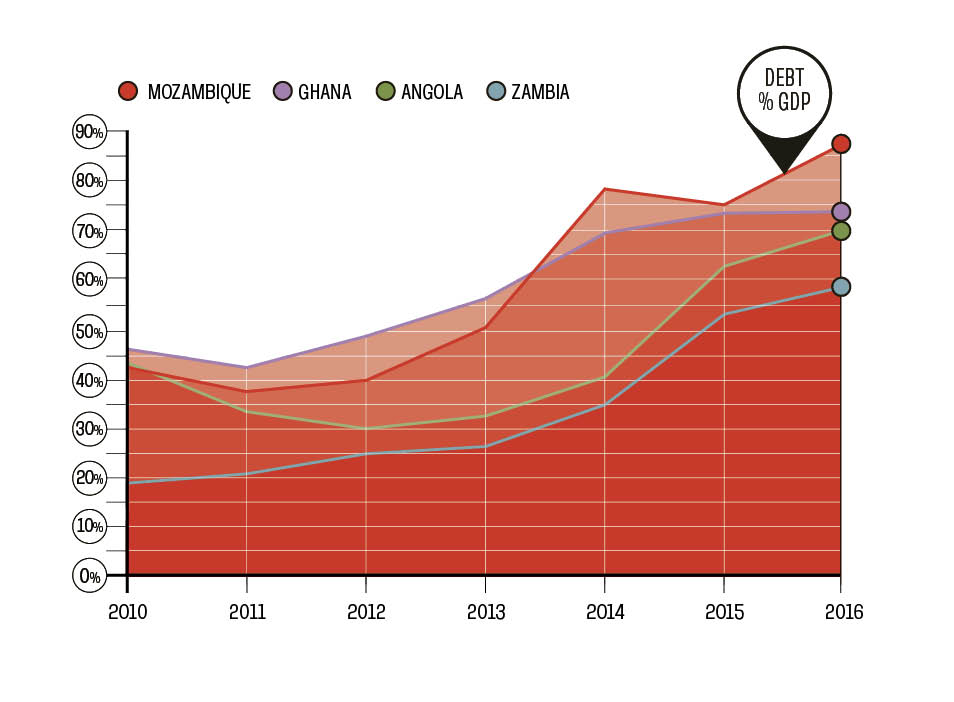

To soften the blow from its lost revenues, Angola’s government has borrowed — first from China, then from the international capital markets. The country issued a $1.5 billion eurobond in November. Now, it has turned to the International Monetary Fund for assistance, asking for a further $1.5 billion in emergency assistance. With that loan, if it is approved, will come demands for more transparency in a notoriously opaque government, and a push for economic diversification.

As John Ashbourne, Africa economist at Capital Economics, says. “It turns out that reorienting an economy away from oil costs a lot of money, and Angola no longer has so much of that as it once did. This is why it is really crucial to invest in diversification during the economic boom. By the time your revenues fall, it is too late to do things easily. It is still possible, but much less pleasant.”

Angola is not an isolated case. Across the continent, other former success stories have stumbled and turned to the IMF for help. Zambia, which relies on copper for 70 per cent of its export earnings, has opened discussions with the fund; Ghana, for several years the poster child of the new, better-managed and democratic Africa, went into an IMF programme in 2015.

Both countries issued bonds on the international markets over the past three years, when investors were keenly seeking out high-yielding assets. Zambia began the rush in late 2012 with a $750 million issue. Gabon, Ghana, Nigeria, Rwanda, Tanzania and Mozambique followed in 2013; Zambia, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia and Kenya issued in 2014, while Ghana followed up with a second issue. Many face the challenge of rising costs of servicing the debt with falling currencies.

Nigeria, which has a relatively diversified economy, but whose government relies on oil, is spending billions to prop up its currency. Even before the Ebola outbreak, Sierra Leone and Guinea were suffering from a slump in the price of iron ore.

In Mozambique in March, the government had to restructure a series of bonds that it had issued in 2013 to fund its fisheries sector; a few weeks later the IMF announced that its investigations in the country had uncovered more than $1 billion of undisclosed debt, and cancelled its programme in Mozambique.

In April, the World Bank lowered its forecast for Sub-Saharan African growth from 4.4 per cent to 3.3 per cent, saying that growth is unlikely to pick up again until 2017-18. The IMF predictions were worse still, saying that the region will grow at 3 per cent this year and 4 per cent the next, both down from

previous estimates.

Hot money is leaving the continent. The S&P All-Africa index lost 20 per cent in 2015; the All-Africa ex-South Africa, which does not include exposure to the larger, often more globally-focused South African companies, was down 28 per cent. The continent’s major currencies crashed, wiping out profits. Between 2013 and 2016, the Angolan kwanza has fallen from 96 to the US dollar to 166. Over the same period, the Ghanaian cedi has dropped from 2.0 to 3.8 to the US dollar; the Zambian kwacha from 5.3 to 9.6; and the Mozambican metical from 30 to 50.

Mthuli Ncube, the former chief economist of the African Development Bank, says that these portfolio flows out of the continent do not tell the full story, and that the long-term potential of its emerging markets is still real. However, he says: “With the recent commodity price collapse, it’s quite clear that some of these African countries have not diversified their economies and have not managed their commodity wealth well.”