The slot machines in Manila’s City of Dreams don’t rattle like they do in the movies. Its permanently lit marble corridors are haunted by the vague smell of recycled cigarette smoke and disinfectant. Easy-listening jazz echoes on an endless loop; a timeless, hermetically sealed consumer limbo with free wi-fi.

Not many people walk out of the complex, preferring to pile into the lines of waiting tour buses that ship patrons out to the Filipino capital’s orbital mega-malls. From the inside there are few gaps in the facade; the windows of the hotel towers look down into a sculpted courtyard of greenery and swimming pools, tended constantly by gardeners in straw campesino hats. But beyond the tangled deathtrap of carpark ramps at the base of the casino, the rest of Entertainment City, a stretch of the coastline given over to the casino business, is barely half-finished.

Asean Avenue, the dead-straight highway connecting the City of Dreams complex to the Solaire, is fringed with wild scrub and dusty wasteland on either side, occupied by a few lonely diggers and bored security guards. To walk between the two casinos means picking through the deep tracks of construction equipment in dust that is quickly smashed to black mud in the short and violent squalls that blow in off the sea. A huge stickman statue is perched on top of the Solaire’s multi-storey carpark, standing precariously on the edge, as though, having lost his shirt, he is contemplating ending it all on the road below.

The punters slumped on the stools by the slot machines in Manila aren’t the high rollers, who are hidden away in the private lounges, playing high-stakes baccarat – the preferred game of wealthy gamblers, offering as it does the best possible combination of good odds and quick thrills.

City of Dreams

Manila’s luxury suites, hidden away in the City of Dreams and its competitors, are becoming a favoured haunt of the mainly Chinese gamblers who can dump millions in one night, as the centre of gravity in Asia’s gambling business moves away from its spiritual home in Macau to new frontier locations, spurred on by an anti-corruption drive in Beijing. However, the risks inherent in this shift towards less-developed, less-regulated environments were laid bare in February.

A hacker or hackers managed to infiltrate the Bangladeshi central bank and began transferring money out of its account in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York by initiating 35 transfers totalling $951 million (£720 million) over the Swift international banking network. A few simple errors in the transfers – including obvious spelling mistakes in the names of the recipient institutions – meant that 30 of the transactions were flagged up as suspect. Five went through, with $20 million going to an account in Sri Lanka, and $81 million to accounts at a branch of the Rizal Commercial Banking Corp in Manila. That money then disappeared into the casino system, mainly through agents and the operators of the ‘junkets’, who bring the country’s ultra-rich to their private rooms.

Manila’s Entertainment City is still under construction, and hopes to attract Asia’s gambling elite

Laundering money through a casino is relatively straightforward, particularly in Manila. All a criminal has to do is bring in the cash, swap it for chips, play a little, and hand it on to an associate to cash out.

Casinos, up until now, have been a black hole,” he says. “That’s where you can make $30 million disappear

It was an accident waiting to happen, says Augustus Caesar ‘Ace’ Esmerelda, a Manila-based private investigator and security consultant who has been following the case on behalf of clients.

“Casinos, up until now, have been a black hole,” he says. “That’s where you can make $30 million disappear.”

At least $29 million went through the Solaire; $35 million passed through the hands of junket operator Kim Wong, who operates the VIP room of the Midas casino. Wong, who has denied wrongdoing, handed back $15 million, but said that the rest had been spent on buying chips for his customers. Most of the money remains unrecovered.

Esmerelda cut his teeth in the security business in a banking sector which, he says, occasionally staged deadly robberies on its own armoured cars as a way to siphon money into political slush funds. The Philippines has got a lot better, but the networks of impunity and corruption mean that anyone with a few good connections and a decent inside knowledge of the banking system could have got away with the heist.

News reports linked the robbery to North Korean hackers. Esmerelda doesn’t believe that, and neither do several other security experts from the region who spoke to Raconteur on condition of anonymity. All of the evidence, they say, points back to China, and the junket operators.

Since being handed back to China in 1999, Macau’s economy has depended on the entertainment business

Macau’s blues

The junket business began in earnest when Macau, the former Portuguese colony on the southern tip of China, was handed back to the mainland in 1999. Searching for a niche led the city’s new government to open up to the euphemistically named ‘entertainment’ business.

Within a decade, Macau was a tropical Las Vegas, its skyline trimmed with neon. Its clients were almost exclusively from Hong Kong and mainland China, where consumers, and particularly the nouveau riche, have an almost insatiable appetite for games of chance, but limited opportunities to play.

The junkets sprung up to channel the wealthiest clients to the tables, offering luxury gaming rooms, top-class hospitality and, for trusted clients, lines of credit to allow them to keep on playing after their cash had run out. Networks of agents in China were – and still are – responsible for recruiting clients on the ground. Commissions for bringing in cash players are considerably higher than those for players on credit. The money in the games was often eye-watering.

“We had high rollers who would come in and lose a hundred million Hong Kong dollars in two or three hours,” one junket operator says, before adding quietly. “Not now.”

Some legitimised, and are even listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, submitting themselves to a degree of regulatory oversight, although even those have struggled to shake off the sense that they work in, at best, a grey area – not least because Chinese currency controls theoretically limit outgoing funds to 20,000 yuan (£2,300), which is less than most of the big spenders drop on a single hand.

It is this sense that high rollers are skirting the law that pushed China, as part of a wider crackdown on official corruption, in 2014. Since then the number of junket operators in Macau has halved. Revenue from the private rooms fell in the same proportion, and Macau’s share of the global VIP business fell from 80 per cent to 65 per cent in 2015, according to a report from Morgan Stanley.

“We have consistently said that while Macau itself is a huge economic success, from a regulatory perspective it has not been as successful,” says Paul Bromberg, chief executive of gaming and investigations consultancy Spectrum Asia. “Many people have been saying that we’re just naysayers and we’ve had it in for Macau, but when the president of China says the same thing [in December 2014], it tends to give credence to your point of view.”

Chinese nationals with assets overseas are concerned about setting off red flags back home as they pass through immigration into Macau. The country’s state security is widely rumoured to be operating within the casinos. China’s economic slowdown has also cut back the spending power of its upper class, and privately, junket operators admit that their bad debt loads have risen.

In May, the Chinese government slammed another nail in the coffin of the Macau junket business, by banning proxy betting – essentially, remote gambling by phone in the VIP rooms.

“Before, we had more than 5,000 active agents. Now it’s down to about 2,000,” says Ryan Yip, an executive at junket company Iao Kun Group. “After May, the department disallowed proxy betting, the business is dropping again.”

Yip says that the impact on Macau has been profound. “In the past few years, if you came to Macau it was full of people,” he says, speaking at a café in the middle of a casino complex, which is almost entirely empty. “Not just in the casinos, also outside on the shopping streets. But right now, it’s different. It’s because of that China government policy. Two years ago, you couldn’t even get a taxi.”

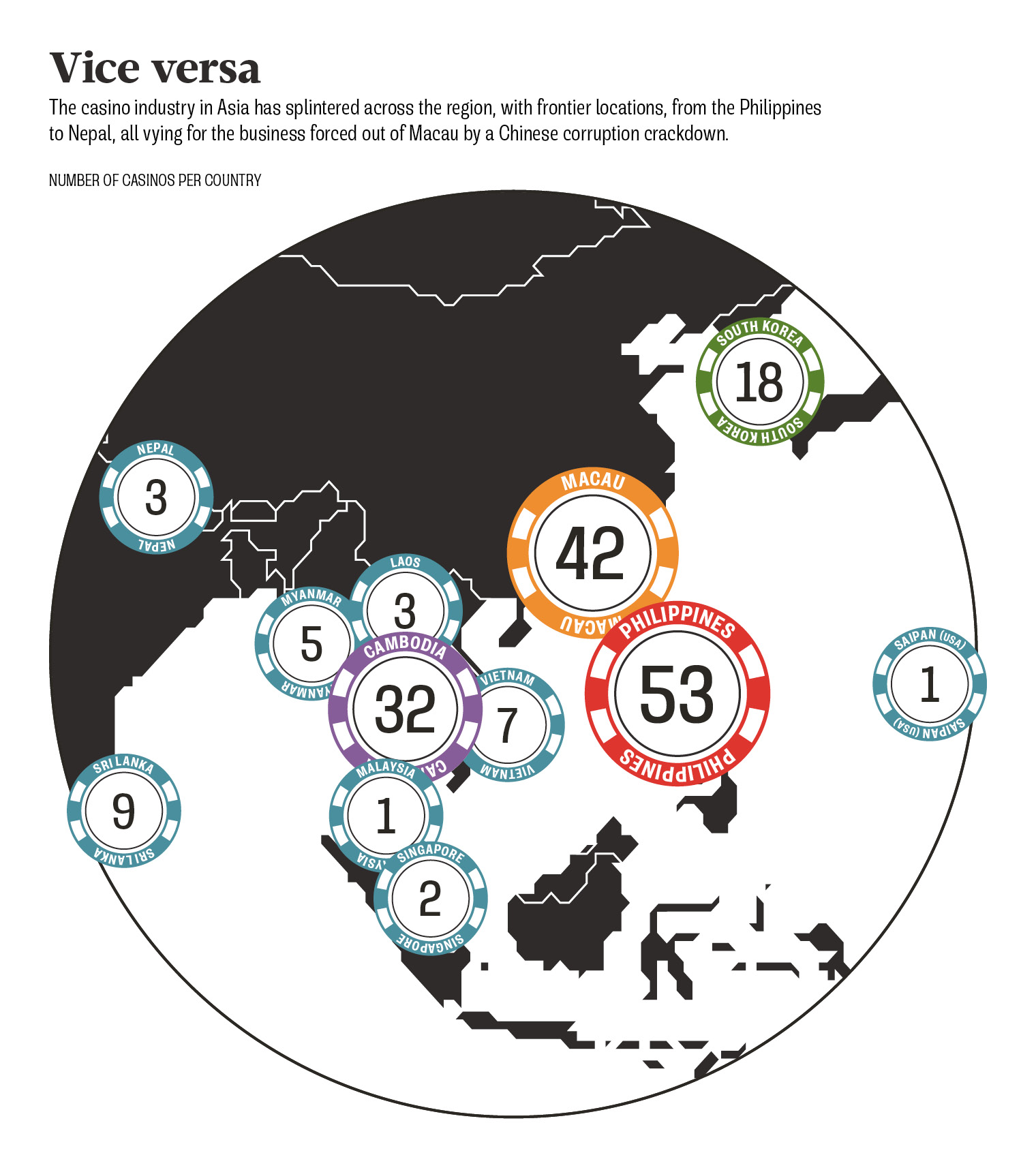

Iao Kun Group has started, like its peers, to shift its focus overseas, working on projects in Jeju, South Korea, and in Cambodia. Across the region, the business is fragmenting, and casinos are springing up from Saipan, a tiny, US-controlled island in the South Pacific, to Nepal, Vietnam and the Philippines.

“If junket clients do not wish to visit Macau then junket operators look for other opportunities in locations that are not, shall we say, as well regulated as Singapore, the US or Western Europe,” says Bromberg. “Obviously the Philippines, Cambodia, Vietnam, are not particularly known for the vigour of their regulation.”

Chinese pressure

Back in Manila, Ace Esmerelda is certain that Chinese pressure has pushed the darker edges of the casino business to the Philippines. The Bangladesh heist may have briefly centred attention on the industry, but the trail has long gone cold. It is also, he believes, not the first time that such a deal has been successfully pulled off in Entertainment City.

“You can’t monitor anything,” he says. “High rollers fly in in private jets, take a chopper from the airport to the hotel, after hours of playing take the same route back. You don’t even know their name. Everybody is paid not to ask questions. When they go back with big suitcases, who is going to ask them questions?”

City of Dreams