Photo: Ahmet Bolat/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

When Jim O’Neill, a former chief economist at Goldman Sachs, conjured up the idea of the “BRICs” in 2001, it was a neat enough concept. China, a new addition to the World Trade Organisation, was just starting its inexorable rise, while India and Brazil, bursting with human and mineral resources, were showing signs of fulfilling their manifest potential. Russia, after the untold miseries of the 1990s, was emerging into the light, under the aegis of a new president.

To O’Neill, it made sense to clump these four giant emerging markets into a single, neat, investor-friendly acronym. As it turned out, plenty of others thought the same way. Most financial research gets filed away or, at best, mentioned in passing by journalists looking to place the complexities of the global economy in context. This paper, bearing the dusty title of Building Better Global Economic BRICs, changed the world, at least for a while.

BRICs was a buzzword, but it had a basis in fact. The four countries were large, politically significant in their respective regions and growing fast.“These countries were all set to be the world’s fastest growing economies in the decades to come, and together they could form a powerful economic bloc,” says Hisham Halbouny, managing director at Man Capital, the asset management arm of Cairo-based Mansour Group.

Investment banks rushed out research and data that aimed to prove the point; fund managers, investors and journalists lapped it up. The acronym became real. In March, Brazil’s long-simmering political discontent boiled over into mass protests, calling for the impeachment of President Rousseff as an economic crisis, precipitated by falling commodity prices, bites. Her predecessor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who presided over the country’s growth spurt, is facing charges of corruption.

Russia entered a recession last year, hit by the oil price crash and international sanctions imposed in 2014 after Moscow annexed Crimea.

China’s economy is slowing as global demand for its products wanes and as the personal debt that fuelled its consumer boom mounts up. South Africa, whose addition to the group meant that the lowercase “s” was capitalised in 2010, has had a turbulent 18 months of drought, power cuts and political bloodletting, exacerbated, again, by falling commodity revenues. Only India remains relatively unscathed.

The acronym was probably already on its last legs — Goldman Sachs closed its loss-making BRIC fund last November, having seen its assets dwindle to $98 million (£68.5 million), from $842 million at its peak — but for a while, the idea really did deliver.

From 2001 to 2014, China’s economy grew by an average of 9.9 per cent a year, India’s by 7.4 per cent, Russia’s by 4.1 per cent, and Brazil’s by 3.4 per cent. The financial crisis was a blip in Brazil, Russia and South Africa, but while Britain’s economy contracted by 4.2 per cent in 2009, China’s swelled by 9.2 per cent, with India not far behind.

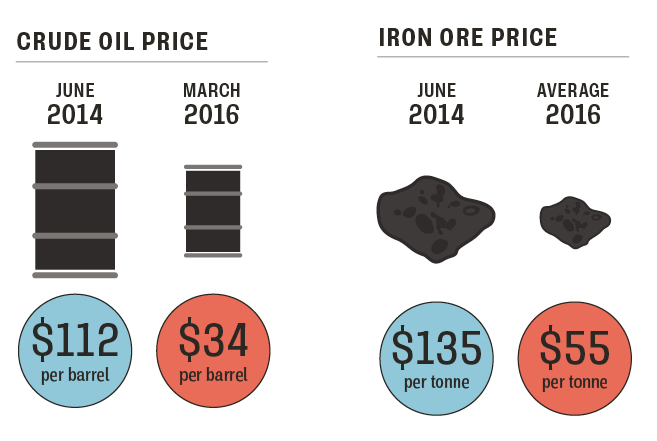

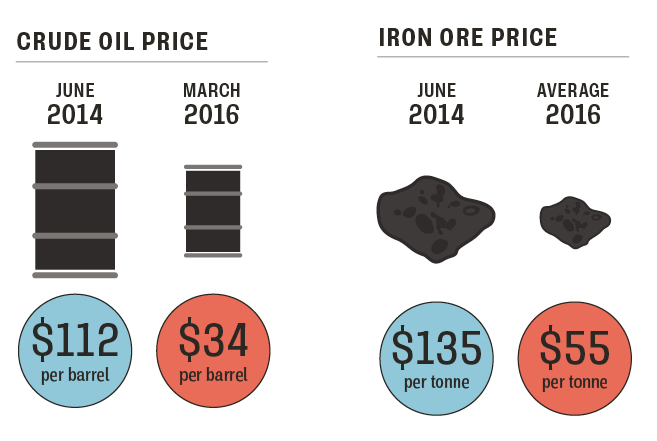

The disparity can be seen over the last year and a half. Countries like Brazil and Russia, which depend on commodities, have had a terrible time

Politically, the five countries bought into the idea — albeit to different extents. Since 2009, they have held summits to talk about their shared interests. In 2014, they banded together to create their own development bank, a competitor to the US-headquartered World Bank.

For investors, emerging markets seemed to offer outsized returns at only marginally extra cost and risk to the punter. In time, investors started to cast around for new toys to play with. O’Neill invented the “MINTs”, a cluster of Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey, also known as the “next row” of BRICS. Then HSBC got involved, dreaming up “CIVETS”, a concoction of bustling frontier markets ranging from Colombia to Vietnam.

In hindsight, the implosion was inevitable. As Sun Global Investments CEO Mihir Kapadia says: “The disparity can clearly be seen over the last year and a half.“The countries like Brazil and Russia, which depend on commodities, with the fall in prices have had a terrible time. Why have the commodities fallen? One of the other BRIC countries, China, reduced its overall consumption.”

And as growth slowed in the emerging world, investors started noticing the bare patches and burn marks. Brazil’s state-dominated economy; India’s aversion to foreign capital; the fact, according to Stephen Parr, a senior investment manager at Aberdeen Asset Management, that “quality companies are thin on the ground in Russia and mainland China”.

BRICS, then, may fall out of use — its imitators never really caught on — but a cursory read over bank research reports shows that economists are still searching bravely for new acronyms. Whether any will stick is a different matter. As Man Capital’s Halbouny says: “The investment community started realising that cramming very different countries into a single investment umbrella did not make much sense.”

[embed_related]

Family values

The economies of the BRICS were never really very similar, and their differences have only grown

Brazil

Exports

Iron ore: 13.5%

Soybeans: 9.0%

Crude oil: 5.3%

GDP 2001: $1,600 billion

GDP 2016: $3,300 billion

Brazil had a difficult 2015, as continuing low prices for iron ore and oil drove down the value of its currency and dented government spending. This year political chaos has gripped the nation, which also faces a giant bill for the Olympic Games.

Russia

Exports

Crude oil: 35%

Petroleum: 17%

Natural gas: 14%

GDP 2001: $1,600 billion

GDP 2016: $3,500 billion

Russia’s economy is heavily dependent on oil and gas exports, and the collapse in prices in 2014 and 2015 has gutted its revenues. Sanctions, imposed after the country’s annexation of Crimea, have added a further element to its crisis.

South Africa

Exports

Gold: 18%

Diamonds: 8.3%

Platinum: 6.8%

GDP 2001: $350 billion

GDP 2016: $740 billion

South Africa’s economy is relatively diversified, and its current economic turmoil has many roots. However, the country is a major exporter of metals, and a tough market for platinum and other minerals has added to its challenges.

China

Imports

Crude oil: 13%

Iron ore: 5.8%

PCBs: 8.9%

GDP 2001: $3,700 billion

GDP 2016: $21,000 billion

China’s export-driven economy supplies developed markets with manufactured goods. Its rapid growth meant it consumed vast quantities of raw materials; its looming slowdown has torpedoed the market for those commodities.

India

Imports

Crude oil: 32%

Gold: 8.6%

Coal: 3.4%

GDP 2001: $2,100 billion

GDP 2016: $8,700 billion

India is the last of the BRICS to fall into a slump. The country’s economic growth has been driven largely by internal consumption, and the low oil price has reduced the cost of its imports, but its steelmakers are suffering from falling prices.

Family values