Above: Sub-Saharan migrants arriving to the port of Corigliano Calabro Italy in June - © 2016 Pacific Press

In Como, northern Italy, a group of unaccompanied children sleeps rough outside San Giovanni train station. Every day, trains leave bound for Chiasso in Switzerland, many filled with migrants and asylum seekers trying to cross the border; Germany and Sweden are the most common final destinations.

Most are reluctant to be photographed. “Italian authorities can track us down through pictures in the paper,” says Adin, a 17-year-old Eritrean. Their biggest fear is being fingerprinted by Italian police, as this would force them to apply for asylum in Italy. According to the Dublin Treaty, the asylum request should be made in the first EU country where the seeker is identified.

Adam, also 17 and from Eritrea, paid around $3,000 (£2,300) to reach Europe – including $600 in ransom, after being kidnapped by militiamen in Libya.

“I tried to cross the Swiss border three times,” he says. “It’s practically impossible sneaking through. They always catch you. I usually hide under the seats, but some hang on underneath the trains.”

As young as 14

Thousands of young Eritreans have fled the country to avoid its policy of indefinite national service. Avoiding the draft attracts serious punishment, and those who are returned face long prison sentences in appalling conditions. Increasingly, those who make it across the Mediterranean, after a long journey overland through Sudan and Libya, are young – Raconteur met children as young as 14 travelling alone in Como.

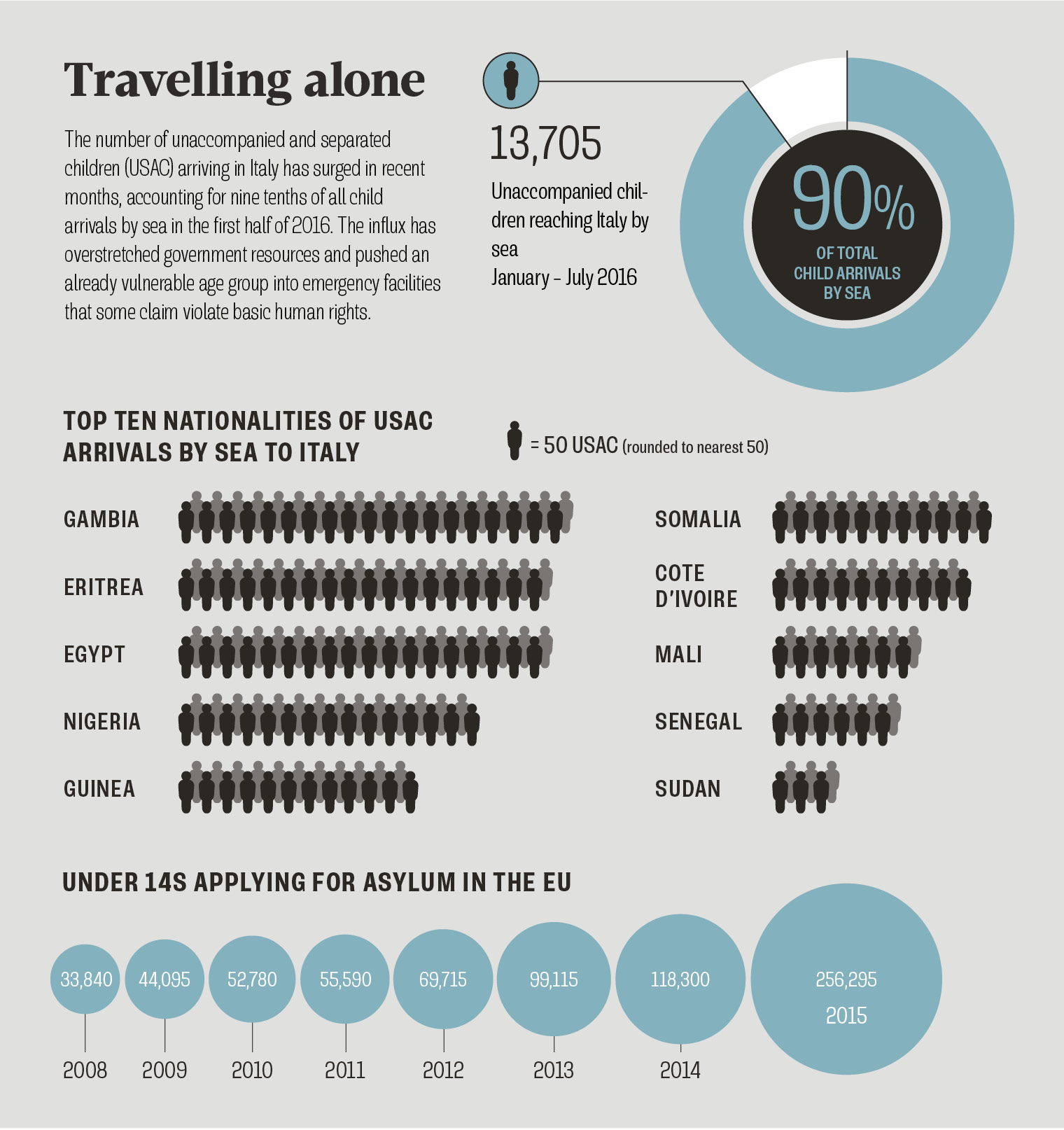

European authorities are struggling to cope with an influx of unaccompanied minors, the majority of whom are Syrian. Figures from the European Union show that last year, a third of all people seeking asylum in Europe in 2015 were under the age of 18; 13 per cent were under 14. Many are unaccompanied. Europol estimates that at least 10,000 child refugees have disappeared since arriving in Europe, raising fears that they could be forced into exploitation.

It’s practically impossible sneaking through. I usually hide under the seats, but some hang on underneath the trains

Charities responding to the crisis warn that there is a chronic shortage of facilities and professional care available for child refugees. Many will spend years on the road or in camps waiting to be resettled, during which time they will lack access to education, healthcare and protective services, which feeds into longer-term issues.

Emergency measures

This problem is further complicated by an increasingly hard line on migration being taken in border states – which is why many of those in Como want to avoid being registered in Italy. The country has been criticised for its inefficient registration procedures and poor facilities. Faced with an overstretched system, the government put in place emergency measures in July.

The new bill means that, when arrival rates rise, the prefect of a region can allow unaccompanied minors to be settled in centres that were designed as short-term holding facilities for older migrants, rather than in more comprehensive accommodation – the Sistema di Protezione per Richiedenti Asilo e Rifugiati, or SPRAR, which hold smaller numbers of children, and provide education and support. Critics claim that this has encouraged regional and municipal governments to stop investing more in the SPRAR in favour of the cheaper holding centres, leaving minors vulnerable.

“The new emergency measures adopted by the state simply go against the International Declaration of Child Rights. Often, emergencies mean a lowering in standards and services,” said Giovanni Annaloro, lawyer and member of Associazione per gli Studi Giuridici sull’Immigrazione, a legal group that focuses on migrants’ rights.

“Many minors end up in these new centres with 50 other people, where it’s impossible to guarantee their integration and protection. Italy must be better prepared for this ongoing crisis and provide these minors with the care for which they are entitled.”

FOOTNOTES

HOLDING PATTERN

Although the UK changed its rules in May to allow 3,000 unaccompanied child refugees into the country, hundreds of eligible children remain stuck in the Calais ‘Jungle’, the refugee camp in northern France. French authorities and local businesses want to close the camp, which is suffering from shortages of food and supplies as donations slow.

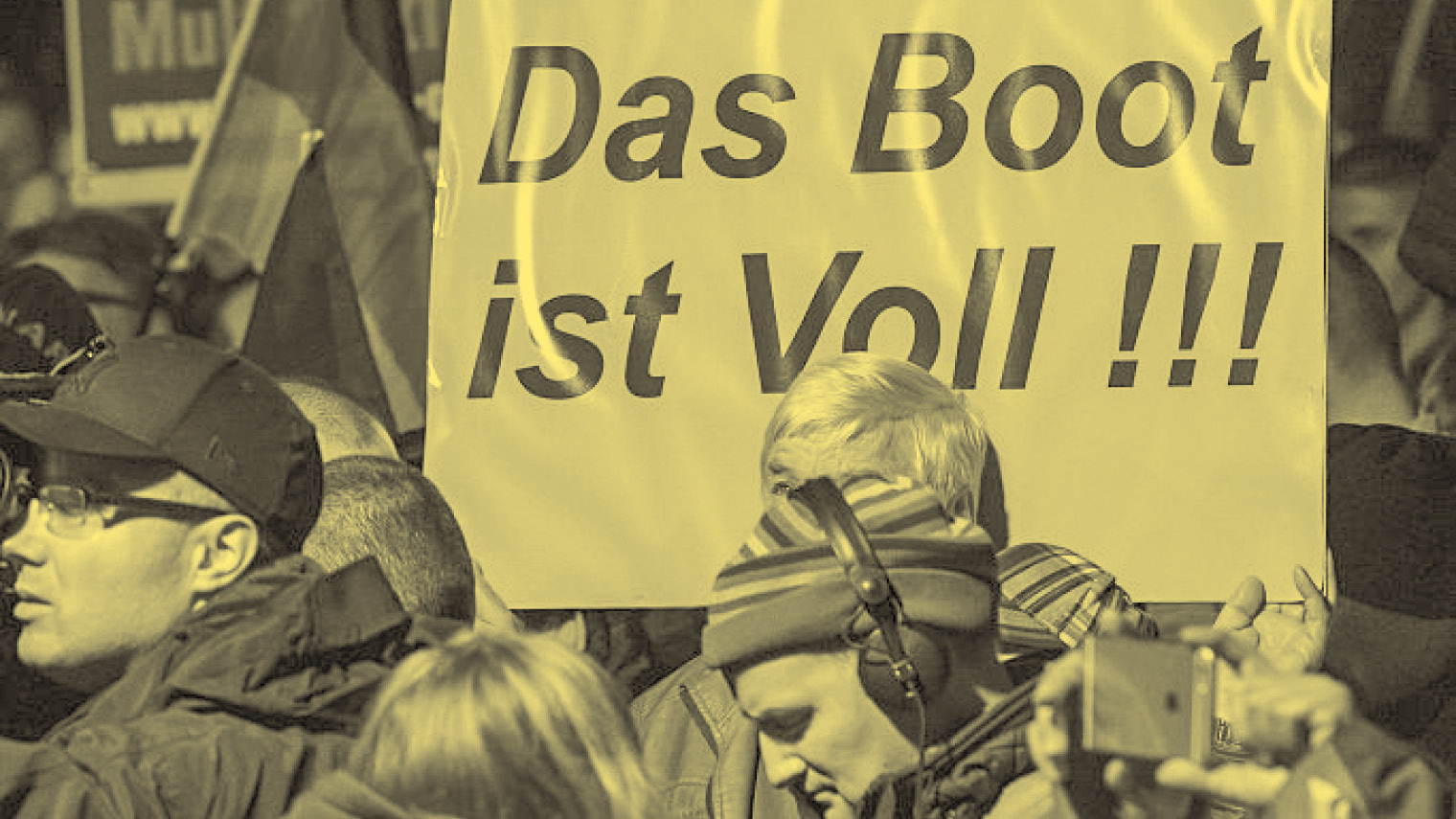

POPULISM RISING

Migration concerns look set to dominate Germany’s 2017 elections, after the anti-immigration populists Alternative für Deutschland beat chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union in regional elections in September. The CDU was forced into third place behind the AfD and the centre-left Social Democrats, in a symbolic defeat.

RECORD EXODUS

12.4 million people were newly displaced in 2015, taking the total number of refugees to its highest ever level of 65.3 million people, according to the United Nations High Commission on Refugees. Over half of those people came from three countries: Syria, Afghanistan and Somalia.

NEW FUNDING

Leaders attending a summit convened in New York in September pledged an additional $4.5 billion (£3.4 billion) on top of their existing support for refugees, including $1 billion from the US. 193 countries signed up to new commitments to safeguard and provide economic opportunities for forced migrants.

As young as 14