Although he appears barely out of his mid-40s, Pablo walks with a stick and a limp. Short and stocky, and with a friendly handshake, there is little to show that until a few years ago, he was a member of the leftist rebel group Las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, known internationally as the FARC. He asked that his full name was not disclosed, to protect him from reprisals.

In 2008 — although possibly earlier; his recollection of exact dates is hazy — Pablo was out of work and struggling. When a friend suggested they could use their skills and make a little money working for the FARC, he joined the revolution.

“I didn’t even know exactly what the job was, I just started working. After a while, I had just become a part of the group.”

Joining the FARC, Pablo explains, meant taking on a new identity and being separated from friends and family for the full five years he was with them. He was blindfolded on the journey to the camp so he would not know its location. Strip searches were routine.

FARC members receiving classes on life after the peace deal

Working for the guerrillas, Pablo would build paths toward the FARC’s jungle encampments, making it easier for horses and equipment to navigate the difficult terrain. However, after half a decade of living under harsh military conditions, he decided he had to leave.

“Life with the FARC is very strict,” Pablo continues. “If you don’t follow the rules, you could be killed.”

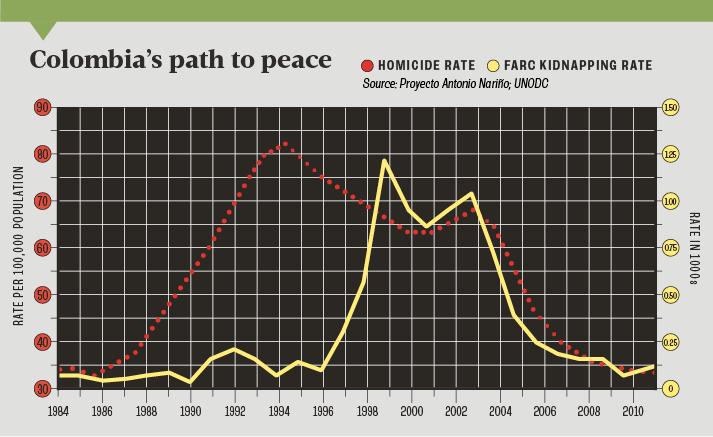

The war fought between the FARC and Colombian government forces has raged for 52 years. It has claimed the lives of some 200,000 people, while a further 5.7 million Colombians have been internally displaced by the fighting.

While the conflict is technically ongoing, peace talks have been underway in Havana, Cuba, since September 2012. The deadline for finalising a peace deal passed on March 23 this year, but both sides claim to be optimistic that they will be able to reach an agreement.

Getting to a peace deal is challenging enough; what comes after could be harder still, as the country works to demobilise and reintegrate former fighters and FARC members like Pablo.

Estimates vary but currently there are between 20,000 and 25,000 FARC members in Colombia. While it is likely that just 7,000 of these are rank-and-file fighters — down from a peak of 18,000 at the turn of the century — the remaining urban militia and support personnel will also need to be included in any demobilisation process that follows a successful peace deal.

“There are going to be a number of challenges,” says Adam Isacson, a senior associate at the Washington Office on Latin America, a human rights organisation.

“One is the cost, which could run well into the hundreds of millions of dollars. Also, unlike the deserters they have had in recent years, these are people who are likely only demobilising because their commanders told them to. They are more likely to not want to participate in demobilisation programs and, maybe in some cases, turn to criminality to make a living.”

Demobilisation and reintegration

Over the last 13 years, the Colombian government has built what is now a highly regarded disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration programme — Programa de Atención Humanitaria al Desmovilizado — spearheaded by the Agency for Reintegration in Colombia.

Since its inception in 2003, the ACR has worked with almost 50,000 ex-combatants from groups including the FARC; smaller leftist guerrilla group the ELN, and the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia, a paramilitary group. To date, 12,912 former combatants have successfully completed the process of reintegration, while 17,250 are currently progressing through the system. Of these, 73 per cent are in employment and 76 per cent have continued to live within legal means, making the ACR more successful than Colombia’s — and the UK’s — prison system.

“Our first challenge is to get communities to accept the re-integrating fighters,” says Juan Fernando Velez, a regional coordinator for the ACR in Medellín. “We also have to encourage businesses and industries because reintegration needs to make economic and legal sense. This is how we start breaking down the cycles of violence.”

Velez explains that around two-thirds of the FARC population joined when they were children, which has resulted in a high proportion of former combatants presenting symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health issues.

30 to 40 per cent of the FARC are thought to be women and children

“Many of these former combatants are addicted to drugs,” Velez says. “This makes it more difficult not just to re-integrate them, but also to get them to stay away from criminality as well.

“The first thing we do when we receive a new combatant who wants to re-integrate into society is to stabilise them as an individual. Then we can focus on the rest of the integration process, which differs from region to region, depending on the social and economic dynamics of each area.”

FARC also still has a large contingent of women and children — perhaps as high as 30 or 40 per cent of its total numbers — who will require more specialised help. Many former fighters may choose to stay in rural areas, making it difficult for them to access reintegration services, while the stigma of having been a FARC member may prevent many from entering the workforce. Keeping former combatants safe from revenge attacks and getting communities and employers to accept them will be vital if the peace process is to stick.

Rodrigo Castillo, the president of Conpaz — a network of 134 communities across 14 of Colombia’s departments — is concerned about reprisals against demobilised combatants.

“We are worried that when the FARC demobilise, they will do so in an environment where other armed groups will attack them,” he says. “Our concern is that FARC members will demobilise and lay down their weapons, only to be executed by paramilitaries operating near our communities.”

Former FARC fighter Salomon Cano attends his own business in Cali

Maria Eugenia Mosquera, Conpaz’s technical secretary, adds: “We want to see peaceful coexistence… We want to live together, to make decisions together. It is very important that the ex-combatants have respect for everyone else and the rules that have been established by our communities.”

However, Castillo is confident that FARC fighters will re-integrate — many have families within the Conpaz communities who will help them to assimilate back into civilian life. The government has also proposed projects, including land titling, education, housing and health plans for demobilised combatants.

But the sheer scale of a FARC demobilisation — 20,000-25,000 in one go, rather than the 18,539 fighters and support staff that have returned to society over the last decade — is alarming for observers of the peace process.

Isacson and WOLA are worried that the ACR and other Colombian government agencies are simply not prepared for a full demobilisation. “They haven’t had to deal with tens of thousands of combatants all at once before,” Isacson says. “I worry about whether or not they are prepared for what’s about to hit them. It’s going to be a huge challenge. and I hope they have a plan B if it turns out they don’t have this under control.”

Overcoming stigma

In reality, the re-integration process will present challenges for any demobilising FARC fighter, regardless of the ACR’s success.

Like Pablo, Yessica joined the FARC because she found herself with no job and no money to support her two children. With the group historically operating out of jungle camps, with bases established near or in rural communities, many rural Colombians have grown up interacting with FARC guerrillas on a daily basis. Consequently, joining the guerrillas is often seen as a reasonable career choice when money or opportunities are limited.

“I joined the FARC because I didn’t have any options and joining them wasn’t difficult,” she says. “Being from a rural community I grew up knowing them and knowing who they were. When I was faced with limited employment options, that’s when I decided to join them.”

The ACR has been helping both Pablo and Yessica to rejoin mainstream society, although the former says that he has been unable to reconnect with his family and his old community.

“At the moment, I am alone in the whole world. My family have all pushed me away. My father died two years ago but I didn’t go to the funeral because I was worried they would react badly,” Pablo says. He has also faced resistance from his new neighbours.

The ACR’s Velez admits that depending on the region or environment, helping to re-integrate former FARC fighters can be harder. “Some communities are more difficult to work with than others,” Velez explains. “Some are very hard indeed, but it is our job to make sure they do not push the ex-combatants away, to make sure they allow them to live among their communities.”

These social challenges will be hard to overcome in a systemic way, but they will be the foundations of any lasting peace. As Yessica says, it is important that people recognise the peace talks are about including everyone in a rebuilt Colombia and not just about ending the conflict.

“We are all human and we do not want to be excluded. We are all a part of Colombia and we ask that people open themselves to us, to our ideas and allow us to be a community,” she says. “I have hopes for the future. These do not depend on other people, they depend on me. I believe in the reintegration process; because of it, I have the tools I need to achieve my dreams.”

Photos: Guillermo Legaria/AFP/Getty images; Luis Acosta/AFP/Getty images; Luis Acosta/Getty images; Luis Robayo/AFP/Getty images