In Can Tho, the commercial and political heart of the Vietnamese Mekong, pleasure cruisers float on the water by night, neon hoardings pulsing across the river while young people lark about on the corniche. It is unseasonably hot and dry. By May, it should be raining here and upstream, filling the river and its thousands of tiny channels, all lined with the orchards and rice paddies that feed Vietnam, but water levels in the lower Mekong are now at their lowest levels since records began.

The Mekong Delta is Asia’s rice bowl; the countries along its lower course — Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar — account for 13 per cent of global rice output. Vietnam is the world’s third largest exporter of rice, and up to 90 per cent of those exports come from the Mekong delta region. Around 25 per cent of the entire world’s freshwater fish catch comes from the river.

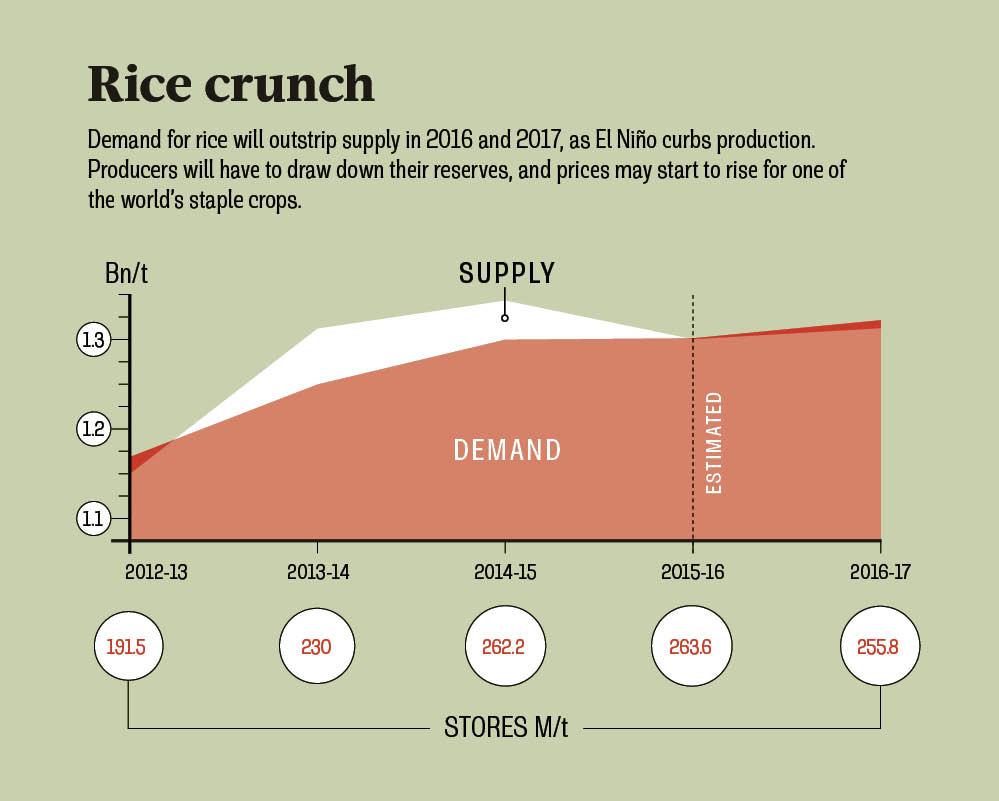

Now the whole region is gripped by a severe drought, the consequence of an unusually strong El Niño, that is damaging agricultural production and undermining food security.

Du Pham, a senior agricultural officer at the Food and Agriculture Organisation and an expert on rice cultivation in the region says that the country has been gripped by the most severe drought in more than 60 years. Saltwater intrusion has extended 20 to 30km further inland than before, and hundreds of thousands of hectares of crops — including 320,000 hectares of rice — have been damaged. Many shrimp, catfish and shellfish farms have been completely lost.

El Niño, an irregular atmospheric event in the central Pacific, has far-reaching impacts. The 2015-16 event has caused vicious droughts from Southern Africa to the Continental USA. It has hit Asia hard. In the Mekong, it has combined with other, alarming long-term challenges of climate change and water shortages caused by dam construction upriver.

At least 11 sizeable hydroelectric dams are planned in China, Cambodia, Laos and Thailand, limiting the flow of water downstream, where the river divides into the nine channels — known in Vietnam as Cuu Long, or Nine Dragons — that form the delta.

Global warming is already having an impact on rice crops in the region, with growing areas experiencing higher-than-average temperatures.

“What we are finding is that there are threshold temperatures above which crop growth will be inhibited and possibly lead to failure,” says Beau Damen, the FAO’s natural resources officer for Asia Pacific.

This is not just one episode. The El Niño today is a precursor of what will happen in the future

“Research undertaken by the FAO in Thailand indicates that some regions of the country are already experiencing average growing season maximum temperatures above a threshold of 34°C, that is resulting in some negative impacts on yields. This finding is supported by the findings of the [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change], which indicate that there are a number of regions in Asia that are already near the heat stress limits for rice.”

Addressing these overlapping challenges will need a renewed focus on improving yields at the farm level, as well as giving farmers access to information and technology to help them to mitigate the risks of a changing climate. Developing early warning systems, which are lacking across the region, would help farmers and policymakers prepare for bad seasons.

“Simple technologies and services such as weather forecasting and crop insurance are still not available to many farmers in our region,” Damen says. Development experts say that the region now has to face up to a new normal of more extreme variations to the climate and to the availability of natural resources, especially water.

“This is not just one episode,” says Sanny Ramos Jegillos, regional disaster reduction adviser for the United Nations Development Programme. “The El Niño today is a precursor of what will happen in the future.” Working in this new normal will require political will at a national and regional level, Jegillos says. All of the countries along the Mekong will need to balance their desire for economic growth and their individual needs for power with the increasing pressure from population growth, new economic activities, and the changing climate.

“All of these things have changed the balance of how water resources will be used,” he says. “It’s really a question of how economic growth will be pursued, and what the implications will be for the availability of natural resources that are required for human development.”

PHOTOS: HOANG DINH NAM/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES