In an embassy pub on the other side of the world, Friday morning’s disbelief had turned to numb shock. There were a few tears, a lot of profanity.

“What happens now?” one man at the bar, a long-term government employee, chews the inside of his lip pensively. “We’re fucked,” he says.

Many here had watched from the early morning of June 24 as it gradually became clear that the United Kingdom had, against expectations, voted to leave the European Union and seen in slow motion the car crash that many back home had woken up inside. The pound was in free-fall, the prime minister had resigned. “We’re fucked” moved rapidly from an emotional response to a consensus position.

It was the wrong result; suicide by plebiscite; won by anti-political guerrilla movements and by their allies in the Westminster class who abandoned reason and turned a referendum on EU membership into a vote of no-confidence in the 21st Century.

The chaos in Westminster that has resulted from the vote has been portrayed as complacency; the idea that no one could believe this would happen. Speaking to insiders reveals a perhaps more alarming truth. There is no plan, because there is no objective: leaving the EU is simply a proxy for a laundry list of social ills, few of which can actually be resolved by a schism in Europe. Many of the shell-shocked people who will have to pick apart this monumental decision, by their own admission, don’t even know where to start.

A protester waves an EU flag in front of the Houses of Parliament as they demonstrate against the EU referendum result (Photo by Christopher Furlong/Getty Images)

For this reason, the timeline is now confused. If the UK is to leave the EU, it will need to trigger Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, setting off a two-year period of negotiations with the remaining member states over the terms of its future relationship. It seems – although it is not a unanimous view – that Brussels cannot trigger that on the UK’s behalf. However, the European Commission and member states can, and might, simply refuse to negotiate without Article 50 being invoked, leaving the UK in limbo.

As many hopeful Remain supporters still maintain, the referendum result is not legally binding – it is only advisory. The government – which is still pro-remain until it is replaced – has only a tenuous mandate to enact the change. Parliament probably should vote on what happens next, and only a minority of MPs have explicitly backed an exit. At the last general election, the UK Independence Party, the only frontline party to have leaving Europe as part of its manifesto, won just one seat. Given the enormity of the decision, a 52-48 vote is a questionable basis on which to proceed.

Leaders in Scotland, which voted overwhelmingly to stay in the EU, can argue that the terms of their devolved government mean that Holyrood has a veto over such a massive decision. The consequence of defying that means of self-determination would be the breakup of the United Kingdom.

In theory and in law there are many ways that the result of the June 23 referendum could be overturned, ignored or massaged to find a less economically devastating solution, but the debate, confined as it is to the minutiae of political and legal challenges, steers British democracy into dangerous waters.

Defying the result would overtly break the democratic contract between politics and society. Going through with it with an administration that lacks a clear mandate to negotiate the terms of exit, or to define the ultimate shape of a more isolated UK, would also represent a clear failure of British democracy. Whatever happens, the profound rejection of the status quo at the ballot box cannot be ignored.

The revenge of the precariat

The roots of that rejection are global and local, and they represent failures of leadership across the British political spectrum. While the right wing of British politics may have exploited discontent to push their own ideologies, the left has consistently failed to articulate an alternative mode of economic and social progress that speaks to the anxieties of post-industrial Britain and its place in a globalised economy.

“Globalisation has left millions and millions of people all over the world as the losers, and a very small group of people at the top as winners,” says Lisa McKenzie, a sociologist at the London School of Economics who studies class dynamics and a global cohort of people dubbed ‘the Precariat’.

Globalisation was a labour market shock; jobs could be offshored, rapidly, disenfranchising whole swathes of the global population.

They voted on the grounds: do they want the status quo, or do they want a change? They voted for a change. They voted on the state of their lives today

“There was a consensus that national politics would put a buffer in,” McKenzie says. “Up until the last 30 years, governments have kind of honoured that, and said that we will have a social contract with workers. That, over the last 30 years have been eroded. To the extent that we now have deficit people. We’ve got people who are worthless, who are not useful in any way at all to capitalism.”

These people are the Precariat. Their social and employment prospects are limited and fragile. In McKenzie’s definition, which places a greater emphasis on class than others, they also have limited social and cultural capital – they may lack the networks and cachet of a university education. Their prospects for social mobility are limited.

Hundreds of demonstrators from steel industry unions gather to stage a protest march. (Photo by Kate Green/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

When metropolitan voices argue that the working class voted out on the basis of issues that are only tenuously linked to Europe, or that are the direct consequence of the UK government’s aggressive pursuit of austerity, it shows an ignorance of the everyday experience of the Precariat, according to McKenzie.

To illustrate, she invokes a man she has been working with in a former mining village in Nottinghamshire as part of a new ethnographic study she is preparing. He was a miner who went on strike during the Thatcher government. Now retired, and suffering from lung disease and white finger, another industrial disease, he voted out for reasons that might seem parochial to the extreme.

“He’s not very mobile. You know why he voted Brexit? Because the bus in his pit village used to run twice a day. There used to be five or six buses, up until two or three years ago, when Nottinghamshire County Council slashed funding. Then there were two buses. It meant that he could go to Wetherspoons, see his mates. And then he could come back home. Last year, the council slashed the funding again, and now there’s only one bus on a Saturday and Sunday. So he can go, but he can’t come back.”

McKenzie is herself angry at what she sees as the abandonment of the working class by Westminster and the often London-centric media.

“Middle class Guardian readers, or people in London, might say ‘he’s thrown our future away because of the bus’,” she says. “No. That’s his life. He’s angry. He’s upset. Are you going to tell him that he should just shut up?”

The more intellectual arguments for leave focused on sovereignty and trade, the more emotive on immigration.

“The Precariat didn’t vote on those grounds,” McKenzie says. “They voted on the grounds: do they want the status quo, or do they want a change? They voted for a change. They voted on the state of their lives today.”

To overturn the vote on those grounds would be inflammatory, and could worsen the dislocation between the people and their representatives. The problem is, they also cannot simply push the eject button either.

[embed_related]

Democratic deficit

“This referendum is a betrayal of democracy, that is being presented as the ultimate democratic outcome. It’s a betrayal,” says Ioannis Glinavos, a senior lecturer in law at Westminster Law School.

Solving the wider array of problems that contributed to the vote to leave “is why we have a political class,” he says. “This is what politics is supposed to be for.

“Asking people the question without having an operational capacity to carry out the result is a travesty. We cannot as we are at the moment have a leave vote, nobody having a clue what to do about it, nobody knowing how to handle the consequences, the leave side having changed its mind about half the stuff they told people, and having the vast majority of MPs pro-remain.”

A general election may be the way forward. (Image: PAUL FAITH/AFP/Getty Images)

A general election may be the way forward; that depends very much on who inherits the Conservative Party; and on whether the political establishment as it stands is willing to crystallise the discrepancies between the open plebiscite of the referendum and the UK’s first-past-the-post system.

Asking people the question without having an operational capacity to carry out the result is a travesty

On the left, the Labour Party has to rediscover its ability to articulate progressive politics to the working classes, or risk losing whole swathes of its electoral base – what heartlands it can still claim as its own – to a resurgent far right who are redefining a militant English identity.

The sudden reappearance of outright xenophobia on the streets – from the well-reported vandalism of a Polish Community Centre in London to hundreds of other accounts of verbal abuse, Swastikas drawn on German cars and racist handbills circulating – is an alarming trend, and one that even the most ardent defender of the Leave campaign cannot reasonably deny is linked to the rhetoric ahead of the referendum.

Putting this back in its box is going to be difficult, and made harder by the fact that the economic backdrop is bleak, and getting bleaker. Worse, the evidence of the 2008-9 financial crisis suggests that the fight against inequality is ill-served by creating such turmoil – in fact, it gets worse.

As Glinavos says: “The tragedy of this is that the people themselves are going to have to suffer the consequences. Who do you think is going to suffer if the economy goes down the toilet because we have to leave the single market, because this is the only way to get the immigration controls that people voted for?”

***

BLACK FRIDAY: THE DAMAGE SO FAR

Leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), Nigel Farage reacts at the Leave.EU referendum party at Millbank Tower in central London on June 24, 2016, as results indicate that it looks likely the UK will leave the European Union (EU). GEOFF CADDICK/AFP/Getty Images

In the early hours of the morning of June 24, Nigel Farage, leader of the UKIP, gave a triumphal speech, trumpeting “a victory for real people” as the pound slumped, then slid, then plummeted first to eight-year, then 30-year lows.

Within hours, the Remain campaign’s ‘Project Fear’ was shown to be anything but. The damage was swift; time will tell if it is reversible.

By mid-morning, the dollar value of those real people’s savings was reduced by 10 per cent. Once the stock exchange opened a few hours later, their pension funds lost more. Shares in banks, insurers and house-builders slumped on the stock exchange, as investors bailed out. fearing that the economy would suffer. The only respite was for gold miners – gold being a safe haven for cash in troubled times.

Traders told Raconteur that by eight o’clock on Thursday night, many had made the call that the vote would be for Remain – buoyed by the strong lead built up in the last days’ polling, and by the betting odds that were predicting a 75 per cent chance of a ‘yes’ vote. They had to rapidly unwind those positions. Some lost their shirts, others their sanity.

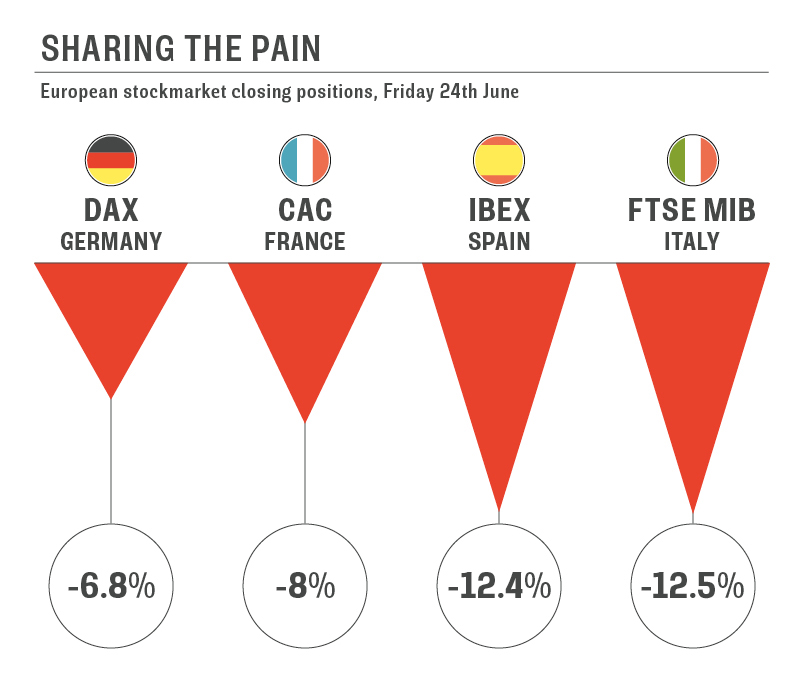

The damage washed up around the world. Across Europe, trading screens were a sea of red. The German DAX ended Friday down 6.8 per cent; France’s CAC was down 8 per cent; Spain’s IBEX down 12.4 per cent; Italy’s FTSE MIB down 12.5 per cent.

Circuit breakers – a damage limitation system – were triggered on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, halting trading in futures. Investors piled into the yen, another safe haven, worsening the prospects for Japanese exporters and pushing the country back towards an economic and political crisis.

All told, $2 trillion (£1.5 trillion) was wiped off global markets by the uncertainty on Friday. Another $1 trillion went the following Monday, and rating agencies Standard & Poor’s and Fitch downgraded the UK’s sovereign rating by two and one notch, respectively. That decision has real consequences on the country’s cost of borrowing and was one of the keystones of chancellor George Osborne’s economic strategy before the vote.

UKIP’s constituents outside of London may not have felt the immediate impact of this Vendredi Noir; indeed some even crowed at the damage done to these metropolitan elites. But financial investors are patient zero in a contagion that is likely to spread widely and deeply into the economy – what is the English for schadenfreude?

On a macroeconomic level, the UK now has to bridge its yawning current account deficit with foreign direct investment, having announced its intention to cleave itself from its biggest trading partner, and from the free-trade area that makes it a hub for a market of 500 million people. The devaluation of the currency may mean, in the long-term, that UK exports will be more competitive. In the short term, it means that the country’s imports will be a more expensive.

Economists are split as to the full extent of the damage, but the consensus is that it will be immediate, and real. The Economist Intelligence Unit predicts the pound will fall 14-15 per cent across the year, and that the economy will shrink 1 per cent this year. Investment banks have lined up to say that growth will be at best flat in 2017. Most forecast a recession.

The revenge of the precariat