Above: The remote Gahcho Kué mine in Canada’s Northwest Territories

Canada’s Northwest Territory in Autumn is an endless wilderness of pine forests, carmine grass and trees turning yellow, pocked with copper-ringed lakes blooming with algae. The plane up from Calgary to the capital, Yellowknife, disgorges a handful of tourists from Japan who stop to take selfies in front of the stuffed polar bear on the baggage carousel.

The nascent tourism industry has been buoyed by a small but significant uptick in visitors from the Far East hoping to see the Aurora Borealis, which are considered auspicious in some quarters; children conceived under the Northern Lights are believed to be set up for a lucky life. Locals may not always agree. After a mining-driven boom in the early-2000s, the territory’s economy hit the skids around the time of the global financial crisis, and has declined more than 15 per cent since its highest point in 2007.

In September, De Beers – the world’s biggest seller of diamonds – formally opened its new Gahcho Kué mine 280km north-east of Yellowknife. It is the largest new diamond mine opened anywhere in the world for 13 years, and something of a milestone for the industry, which has had to invest heavily in expanding production at its existing mines, and to dig deeper to tap the last reserves of diamonds in the ground.

“New diamond mines don’t happen very often,” says Kim Truter, chief executive of De Beers Canada, speaking on the edge of the pit at Gahcho Kué. “If you look typically, from discovery to bringing a diamond mine to production takes about 20 years. So this mine is 20 years in the making. That’s a big deal… for the region it’s a big deal, because for some of the surrounding diamond mines the end is in sight.”

De Beers’ Snap Lake mine, 80km to the north-west of Gahcho Kué, was shut down in 2015, with the loss of several hundred jobs. Victor mine in Ontario is also due to run down in 2018.

For the region it’s a big deal, because for some of the surrounding diamond mines the end is in sight

Adam Bell, Yellowknife’s deputy mayor and a local realtor, says that although the Snap Lake closure did not have a major impact, Gahcho Kué’s opening is a shot in the arm. “There’s considerable upside; there are indirect and induced economic benefits,” he says. “It has huge impact, and more opportunities down the road.”

De Beers says that the mine will employ 530 people directly, and contribute C$5.3 billion (£3.1 billion) in taxes to the region over its lifespan. It has invested C$1 billion in bringing the mine to this stage.

Gahcho Kué is a massive open pit mine, a rare prospect in an industry that has had to dig deep, expensive mines to find diamonds

Hard times

As production has been getting more expensive, the industry has also been coping with a slump in the price of rough and polished diamonds, which fell 15 per cent and 8 per cent in 2015, respectively, according to research from the consultancy Bain & Co. Retailers, particularly those in China, had overestimated demand and overstocked, leading to a glut of supply that choked up the so-called ‘midstream’, where the stones are cut and polished.

Paul Ziminisky, a New York-based independent diamond analyst, says that the oversupply seems to have cleared, and that buying has been strong at the major trade shows in Mumbai and Hong Kong ahead of the main retail seasons of Christmas and Chinese New Year. “So far, it’s been relatively healthy, it’s back to the normal five-year trend,” Ziminisky says.

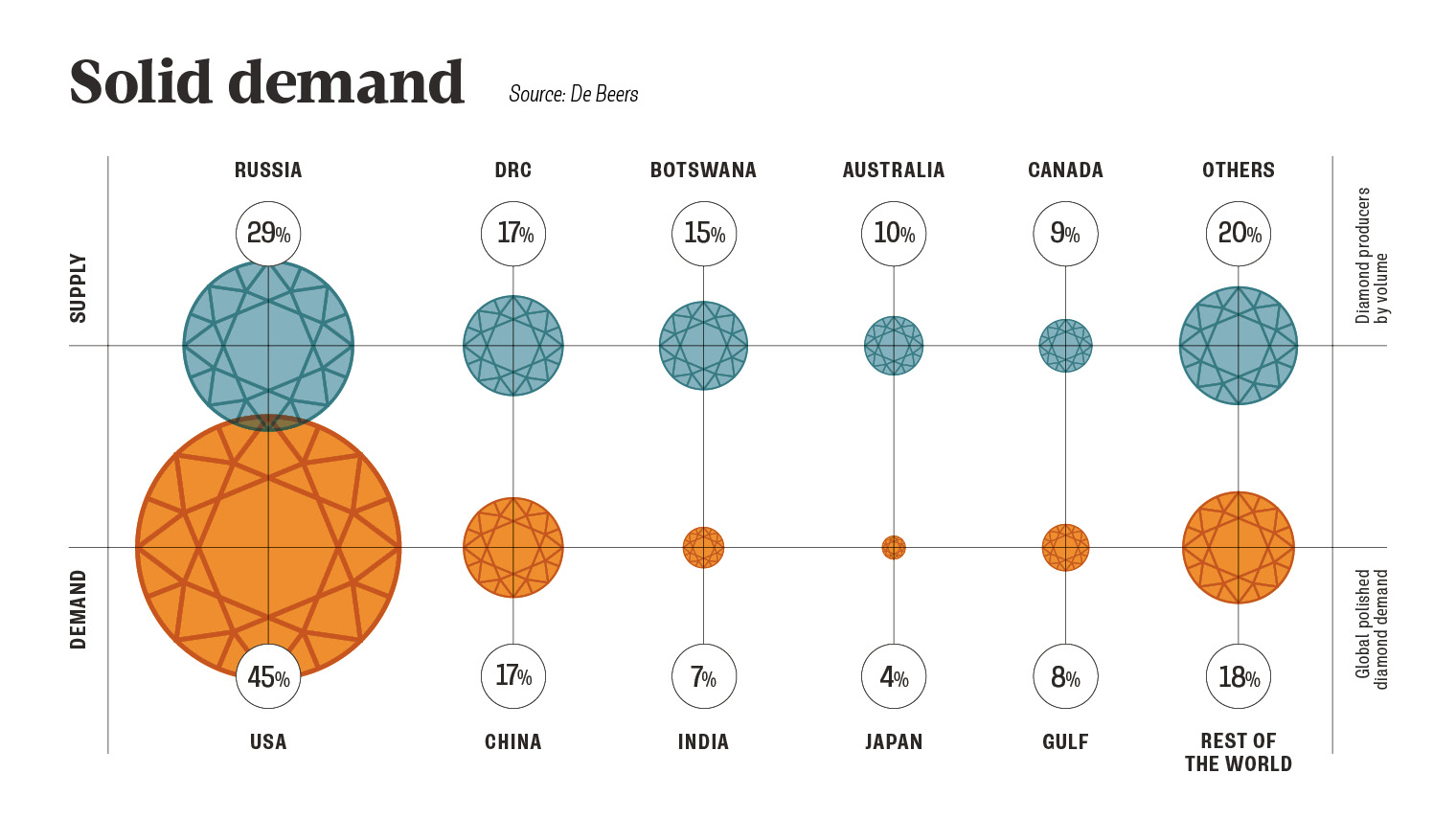

Whether demand really picks up depends on Chinese consumers. The US, the world’s biggest diamond market, has remained relatively stable throughout the downturn, but Chinese customers have been hit by a slowing economy at home. Many have historically bought overseas – only around a third of Chinese luxury purchases are made in mainland China – but the strong dollar and yen, as well as security concerns after the November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, have trimmed their spending.

De Beers is confident that the market will stabilise, demand will rise and supplies will tighten in a few years, making the investment in the Northwest Territory a safe bet.

A long way from anywhere

Reaching Gahcho Kué means taking a 45-minute flight out of Yellowknife over empty tundra, landing on a gravel airstrip on the edge of the mine. Access overland is possible only in the middle of winter, via a 400km ice road, which opens at the start of February and lasts for no more than 60 days. That is their sole window to bring in heavy equipment and the vast quantities of diesel needing to keep the place running.

Huge generators power everything from the quarters for the 280 staff on site to the massive rattling processing sheds that crush and shake out the kimberlite ore that holds the diamonds. This year, the site brought in 22 million litres of fuel up the winter road. Next year, that will rise to 47 million litres, as it ramps up to full production.

The mine will run 24-7, even during the dead of winter when the sun barely rises. When temperatures drop to below -40ºC, the workers’ exposure to the weather is metered, so they can only go out for a few minutes at a time, swapping out with their colleagues to complete even basic maintenance tasks. Work stops only for white-outs, when the snow blows in and visibility is down close to zero.

All around the site, red boxes marked with the silhouette of a bear hold emergency air horns, in case any of the creatures wander into the area. Wolverines and wolves also present potential hazards, although the only animal visible on the eve of the opening was one of the huge white rabbits for which the area is named; in the Chipewyan language, gahcho kué means “a place where big rabbits are found”.

De Beers has had to put in place a comprehensive environmental plan to minimise its impact, and prepare for the site’s decommissioning in the future. The mine overlaps with the traditional lands of six First Nations groups, who do have a number of partnership agreements with De Beers, but who worry about the impact on the migration routes of caribou, which have enormous cultural significance.

Chief Edward Sangris of the Yellowknives Dene First Nation, who led an traditional ‘feed the fire’ ceremony on the day that Gahcho Kué opened, offering up food and tobacco to bring luck to the endeavour, says that while the industry has brought employment over the last 20 years, the influx of money and disruption to traditional livelihoods has created social problems.

“As leaders, we have to walk a fine line between environment and economy,” he says. “We say no, and our people don’t have work; we say yes and our wildlife disappears.”

Hard times