Illustrations: Tim Whitlock

Amir-Abbas Fakhravar was celebrating New Year in Tehran on the last day of 2000 when the knock came on the door. Five plain-clothes policemen stood outside, waiting to take him away.

He was not unduly worried. “It wasn’t my first time,” he says, his voice steady and measured. “They’d arrested me 19 times before on charges of political activism, stretching back to my high school days as a 16-year-old. I’d been in jail on and off for nine years; when I wasn’t behind bars, I was catching up on my law school studies.”

This time was different. The hardliners that ruled Iran with an iron fist had grown tired of his antics. To Fakhravar, liberty and freedom were ideas worth fighting for. To the clerics, they were heretical and treasonous. It was time, they decided, to teach the young rabble-rouser a lesson in the real use of absolute power.

Fakhravar, a slight man with troubled, sunken eyes set in a pretty face, was transferred to Evin Prison, a penitentiary where rapists, drug traffickers and serial killers huddle alongside countless prisoners of conscience: one of Iran’s nastiest gulags. His fate lay not in the prison’s dank underbelly, but in a tiny space devoid of all sound, taste, colour and human contact. A room that, Fakhravar says, could conceivably be described as “the worst place in the world; a place where your nightmares go to have nightmares.”

No one knows who invented so-called ‘white torture’. Some say the Soviets or the Iranians; others, the British or the Americans. But what is undeniable is that is very nasty indeed.

Modern torture methods

On the day of his arrest, Fakhravar was stripped bare, clad in white cloth slippers and a pair of white pyjamas. He was led into a tiny, padded, white and windowless cell flooded with piercing white light, and left alone. Later that day, a white tray filled with white rice — and no other sustenance — was pushed through a hatch in the door. He ate and defecated in the tray. Later, he was led away, silent and blindfolded, to wash the tray, then returned to his own personal hell, a mausoleum for the living. Even now, Fakhravar finds it hard to explain the sheer misery of this form of torture.

“Nothing can prepare you for the full horror of it,” he says. “Go and lock yourself in an empty closet for a few hours, let yourself out, then go back in for 24 hours. And do it day after day after day. I slowly went physically and mentally numb. No news, no noise, no one to talk to. That was my life for eight solid months. The only colour I saw was my own shit. The only fun I had was being let out to wash my tray.”

No news, no noise, no one to talk to. That was my life for eight solid months. The only colour I saw was my own shit

As time stretched out, the demons started to crowd in. “I couldn’t remember my family’s faces. Even my mother’s face. When I dreamed, they were all deformed, calling out for me, and I was powerless to help.” The cell was too small for him to lie down in. “So I would walk to tire myself out. Three feet forward, three back. I still do it when I cannot sleep. I’m doing it right now, as we talk. It’s an impossible habit to break.”

Eight months after walking in, he finally had cause to smile. “The guards took me from my cell and beat me. They broke my wrist, a few ribs, my nose, my collarbone. But it was the best day of my solitary confinement as they were angry, and I knew this meant they were letting me go.”

Never fully free

He was let out, but Fakhravar found that freedom is about more than the unshackling of bonds. He was embraced by friends and family on his release, but says he found the sound and fury of modern society too much to bear.

“I couldn’t listen to people, even when they were laughing and singing,” he says. “Noise was sandpaper to my ears. So I walked to northern Iran, built a wooden shack in a forest, and lived in it for a year. I was sort of happy there.”

Fakhravar’s horror story underlines how much torture methods have progressed in recent years, and at the same time, how little they’ve changed. Humans, says Daniel Diehl, co-author of The Big Book of Pain — a collected history of misery — inflict sustained pain on others for two basic reasons. First, to assert control through terror. This is most commonly found in fragile nation states run by dictators, religious zealots or absolute monarchs: think here of Stalin, Henry VIII, Pol Pot, North Korea’s Kim dynasty.

The second motivation is simple sadism. “Those who inflict torture do so because it gives them great emotional — often sexual — gratification,” says Diehl. “This has been true since the earliest despot threw his enemies into a fire.”

To many, the abiding memory of the Allied invasion of Iraq was not the toppling of Saddam Hussein, but the face of US Army reservist Lynndie England, giving the camera a smile and a thumbs-up from behind a pile of naked prisoners in Abu Ghraib jail.

This urge to inflict pain — and its corollary, a desire on the part of masochists to absorb it — is as much a visceral and emotive part of the human construct as, say, laughter or love. Throughout history, the theatre of it has been fetishised: Vlad impaling his enemies; medieval dungeon masters tying victims to the rack, or roping them to the Judas Cradle; ancient Greek lawmakers roasting petty criminals alive inside great brass bulls.

[embed_related]

In his book The Better Angels of Our Nature, Steven Pinker charts the recent decline of violence and murder across the world, from London to Lima to Lagos, and concludes that we are becoming nicer as a species. Others would argue that we have simply become more squeamish, or that those likely to torture — such as nation states or those working on their behalf — are just becoming better at hiding the evidence by inflicting internal pain that leaves invisible scars.

This makes sense, given the rise of technology. “Anyone can take a picture with a smartphone, so the tendency these days with torture is toward things like sleep deprivation, white torture, or making dire threats about your family,” says Yuval Ginbar, a legal adviser at Amnesty International in London. “These are viewed by some as ‘soft’ torture methods that leave you in extreme pain, but with few marks to show to the public or your family.”

White torture

The War on Terror

Talk to enough experts on the subject of modern torture and a single date stands out. The world changed on that unseasonably balmy morning in September 2001, when two jetliners, piloted by terrorists, slammed into New York’s Twin Towers. It divided the world into ‘pre-’ and ‘post-’ 9/11 eras. After the deadly attacks, the White House under George W. Bush became enamoured with ‘enhanced interrogation’.

Thousands of suspected terrorists were banged up in Guantanamo Bay or carted off to ‘black sites’ in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, to be beaten, waterboarded, or forced to endure psychological and psychosexual torture.

“The more sophisticated psychological methods of torture now used – deafening music, flashing lights, forcing people to stand still for hours on end – it’s all post-9/11 stuff,” says Toby Cadman, a human rights lawyer at Nine Bedford Row in London. “I went to Guantanamo Bay to file a report on the state of the inmates. There was one particularly nasty guy there who should never be let out. He had a prosthetic leg so the guards would make him take it off and stand on the good leg all day long.”

That is not to say that all torture in the era of the smartphone and the hidden camera has come over all clever-clever. It can still be simple and brutally atavistic.

“We have this skewed picture that all torture involves the CIA and waterboarding,” Ginbar says. “The vast majority of torture involves little people in poor places that nobody cares about being casually beaten by the authorities.”

In late 2014, a forensic photographer employed by the Syrian Army fled Damascus with more than 55,000 photos saved on flash drives. Verified by the Holocaust Museum in Washington, the images expose the visceral cruelty of the foot soldiers of the Assad regime. Prisoners held by Syrian intelligence and security agencies stare at the camera with emaciated eyes. Escapees speak of barbaric methods, ranging from inmates being starved or flayed to death, suffering electric shocks, having their eyes gouged out, or being forced to ingest toxic chemicals.

Those in the images were “starved, beaten and tortured in a systematic way and on a massive scale,” says Nadim Houry, deputy director at Human Rights Watch’s Middle East and North Africa division. “They show a fraction of the people who have died in Syrian government custody.”

The Maldives

Far from the Middle East, Ahmed Naseem harbours his own memories of unspeakable cruelty. A fiercely intelligent, silver-haired gentleman with piercing light-brown eyes, Naseem spent six years in solitary confinement on the Maldivian island of Dhoonidhoo, a stone’s throw from golden beaches and bronzed holidaymakers.

“The room was seven feet by five feet, lined only with plastic sheets,” he told me. “There was no door, just a gap in the plastic, inviting you to escape. The guards wanted that: they wanted you to run so they could catch and beat you.”

Naseem was a political prisoner during the regime of Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, who ran the tropical paradise of the Maldives with an iron first until 2008. Yet despite going on to become foreign minister under the country’s first democratically elected president, Mohamed Nasheed, who is now living in exile in London, Naseem still lives with the demonic memories of his incarceration.

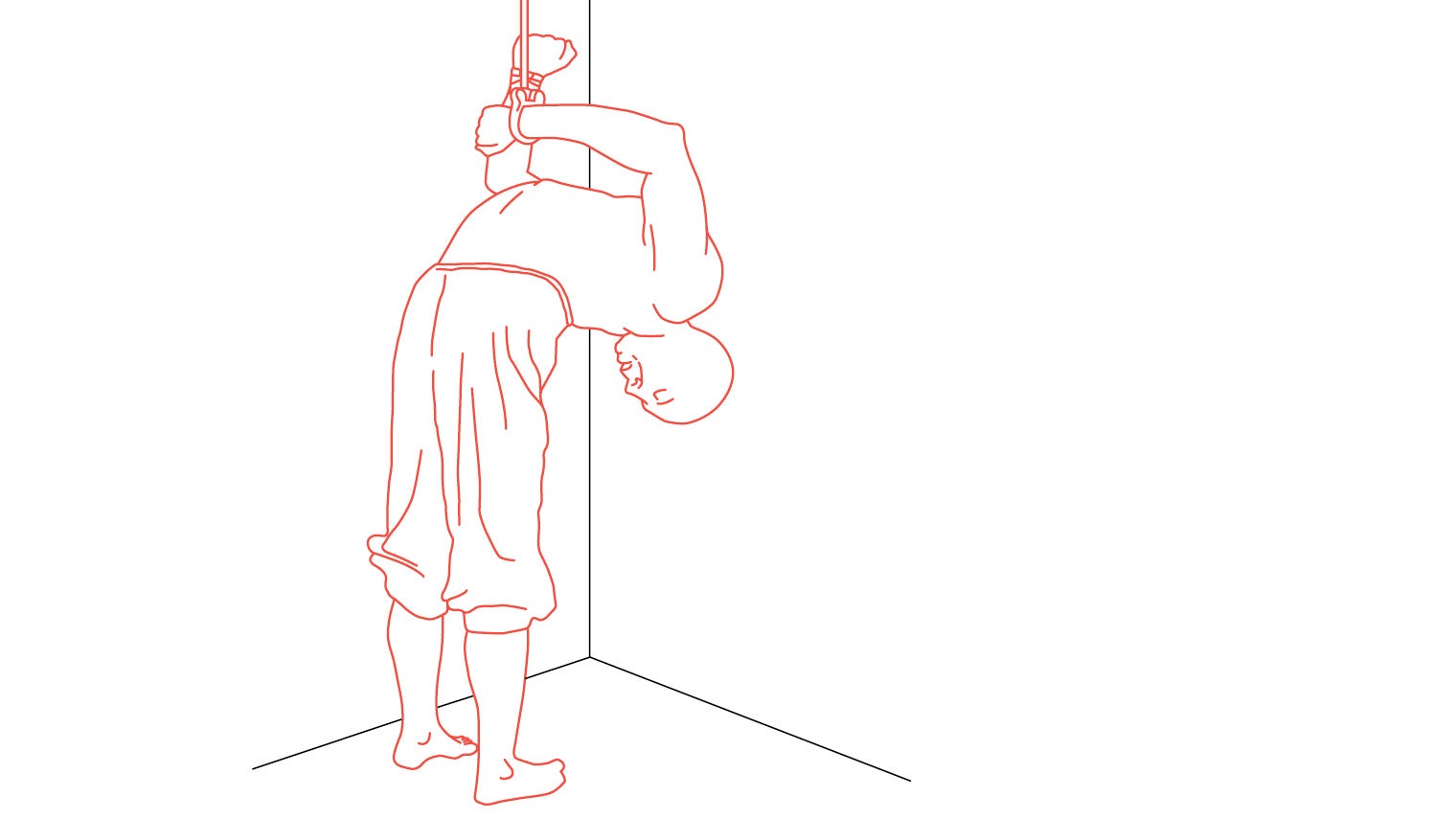

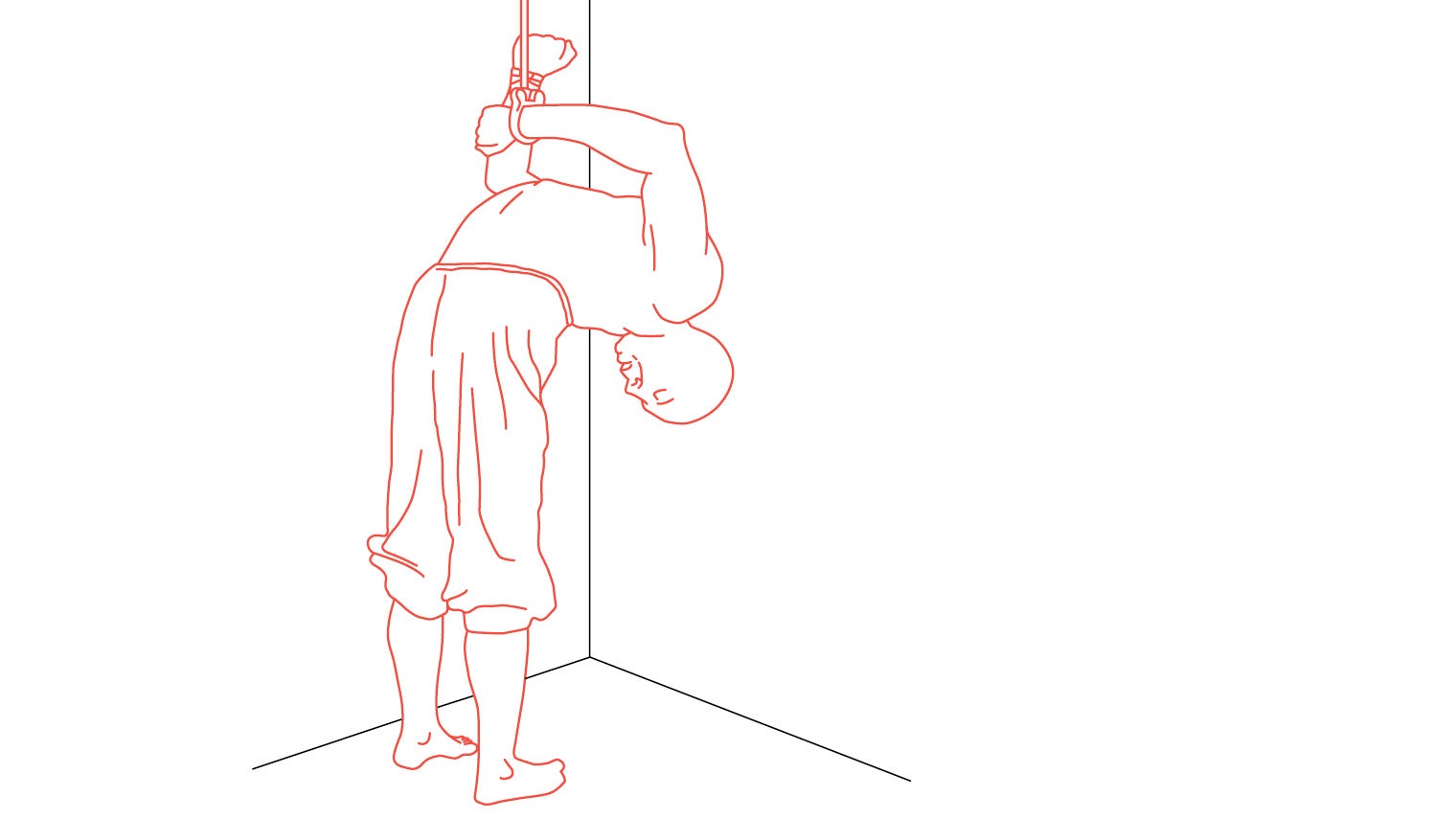

He rolls up his trouser to leg to reveal a series of thick, corded scars running the full length of both shins. “They got bored of me and wanted me out of the way, so they strapped me into the pillories, a barbaric ancient device made of wood and steel, and bent my back nearly double.

“Whenever I moved, jagged and rusty strips of metal would tear open the flesh on my legs, which would re-heal and re-tear, over and over. I was in there for 27 days and they only let me out because they thought I’d died. When they saw I hadn’t, they threw me back in solitary.”

Naseem adds that by comparison, he had it easy. “They brought in others who were flogged to death, beaten, murdered. I saw a man hung upside down and coated head to foot with jaggery [a thick cane syrup consumed heavily in South Asia]. There, he was consumed alive by fire ants. Stripped to the bone.”

Psychological torture

Fakhravar’s ordeal did not end with his release. After returning to Tehran from the forests of northern Iran, he was re-arrested and tried in the country’s Islamic Revolutionary Court. He was attacked with a knife in the courtroom — by the judge — then sent to a supermax prison. His abiding memory is that of his father’s face.

“He was 50 years old, and he’d just retired as a decorated Air Force pilot,” Fakhravar says. “It’s the last memory I have of him: in pain and sobbing. He died the next year in a car crash when I was in prison. I never got to see him again.”

Fakhravar survived prison by the skin of his teeth and fled to the United States, where he became a published author and a constitutional law professor at Texas State University. His latest book, Comrade Ayatollah, is currently being translated into English.

The physical abuse that both Naseem and Fakhravar suffered was extreme, but both, separately, say that solitary confinement — which remains legal in the US, and to a more limited extent in Britain — was far worse.

“Nothing can prepare you for the full horror of it,” says Fakhravar. “I stayed sane by praying, and inventing stories in my head. But I have friends who went in normal and came out of solitary with their minds blown to pieces. It’s the most brutal form of torture there is.”

Never fully free