Singkil, in South Aceh, is where the swamp meets the sea. The road from Subulussalam snakes through it, following the course of the Alas River to its mouth, then veering left along the coast.

On the southern side, the Indian Ocean breaks against Sumatra’s shore, the spray from the wave tops just visible through the trees; on the other, a dark-red mud track runs into the peatland forest. It is early November, and the near-daily rainstorms have soaked the earth, making it a brutal struggle through the thigh-deep peat to reach solid ground. At the end of the track, a tunnel has been smashed through the trees, leaving broken trunks and turned-over soil.

“That’s just happened today,” says a chain-smoking, whip-thin activist who seems able to skate over the top of the peat, pausing only to light up. A local informant has tipped off an Acehnese environmental organisation that Ahmadi belongs to, and he has come to investigate. It is barely noon.

This is the southern edge of one of the world’s last great, relatively complete areas of tropical rainforest, the Leuser Ecosystem, and it is being eroded, acre by acre. Further down the road, a wide swath of forest has already been cleared, the earth and the vegetation stripped back to almost nothing and bleached to the colour of pale ash. Ahmadi’s team filmed from a drone as five men and a digger tore the forest down in a matter of days.

Both areas are inside a wildlife sanctuary; both have been cleared for oil palm. There are already small plantations along the roadside – perhaps a year old – the trees almost comically wide and short, as though full-sized palms have been hammered into the earth like nails. Asked if any of it is legal, Ahmadi’s laughs. “Of course it’s illegal. It’s all illegal.”

A few miles away, on the edge of the peatlands, two white billows mark out the chimneys of a palm oil mill. Because of the unique, and mostly opaque, structure of the palm oil industry, it is highly likely that the fruit from these illegal trees will end up in the international supply chain, feeding into the global consumer goods business and ending up in shopping baskets worldwide. This is the sharp end of an industry, fuelled by demand for convenience food and cheap cosmetics, whose march across the tropics has already been environmentally devastating, and whose organisation means it must ceaselessly expand.

The resulting oil is in more than 50 per cent of supermarket products. It is in the toothpaste, shampoo, shower gel and soap that consumers wash with in the morning, in their breakfast cereal and bread, in their chips, crisps and cakes, their packaged sweets and snacks; even in many of their cleaning products, from washing-up liquid to detergents and laundry powders. But few consumers in major markets are aware of how it gets there, or the damage it has done along the way. Perhaps more concerning – almost all of the companies that buy palm oil to put in food or cosmetics don’t know where it has come from.

In that black spot, palm oil producers have cut into globally significant natural resources, with profound impacts on the climate. Last year, it was peatlands like Singkil that were set alight as 2.5 million hectares of forest were burned to make space for agriculture.

Those fires sent up clouds of smoke that shrouded cities across Southeast Asia, causing an estimated 100,000 premature deaths. As the Indonesian president, Joko Widodo, flew into Paris in December 2015 for the Conference of the Parties climate negotiations, large areas of his country were still smouldering. The World Resources Institute estimated that during the most intense period of fires, in September and October 2015, Indonesia was more often than not a larger carbon emitter than the USA.

This year, the fires have been kept in check – as much by the weather as by efforts from industry and the Indonesian government – and international attention has waned. But on the ground the deforestation continues, eating away at rainforests that are one of the last great bulwarks against catastrophic climate change.

The story of palm

It is hard to visualise the sheer scale of the palm monoculture in Asia. All across the Indonesian archipelago and up into the Malaysian peninsula, oil palm runs in long straight lines, a repeating pattern draped over the countryside. Indonesia and Malaysia, combined, account for more than 85 per cent of global palm oil production. The former has 8 million hectares of land given over to the crop, double what it had a decade ago.

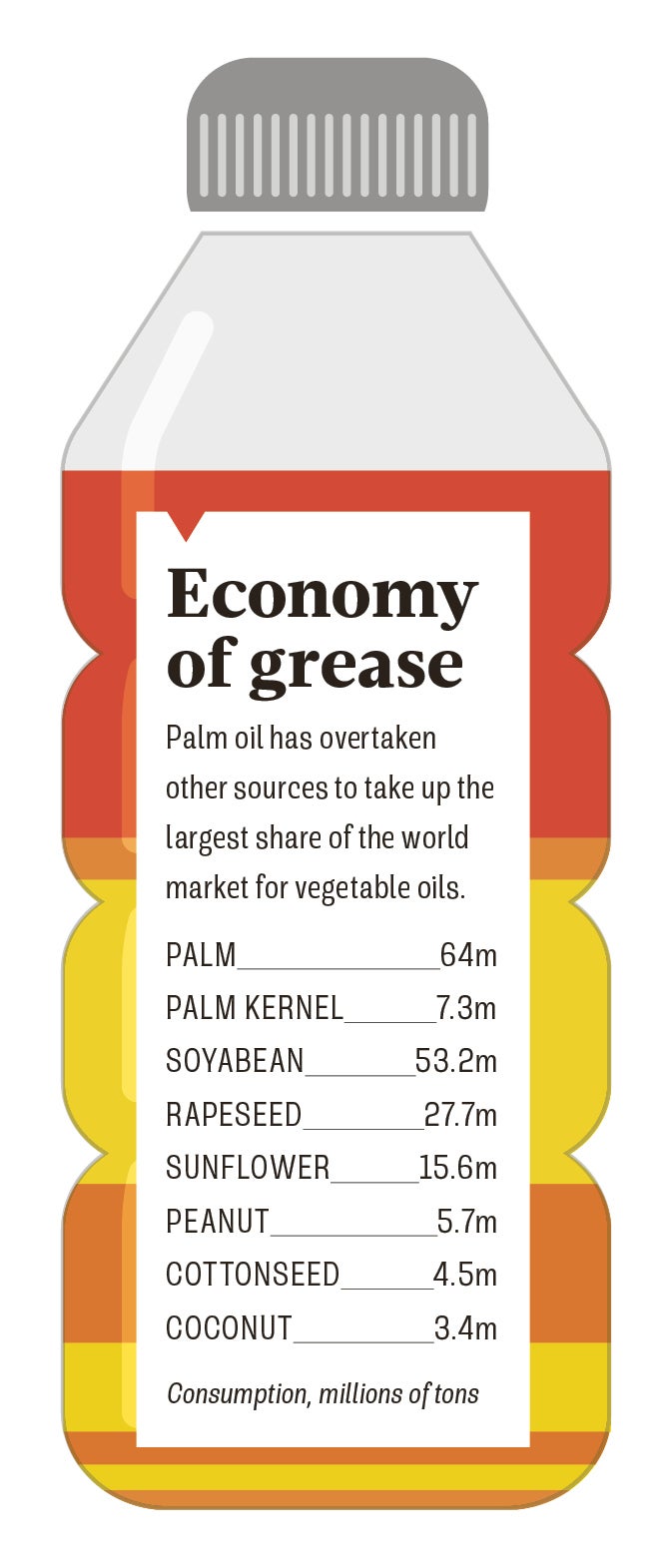

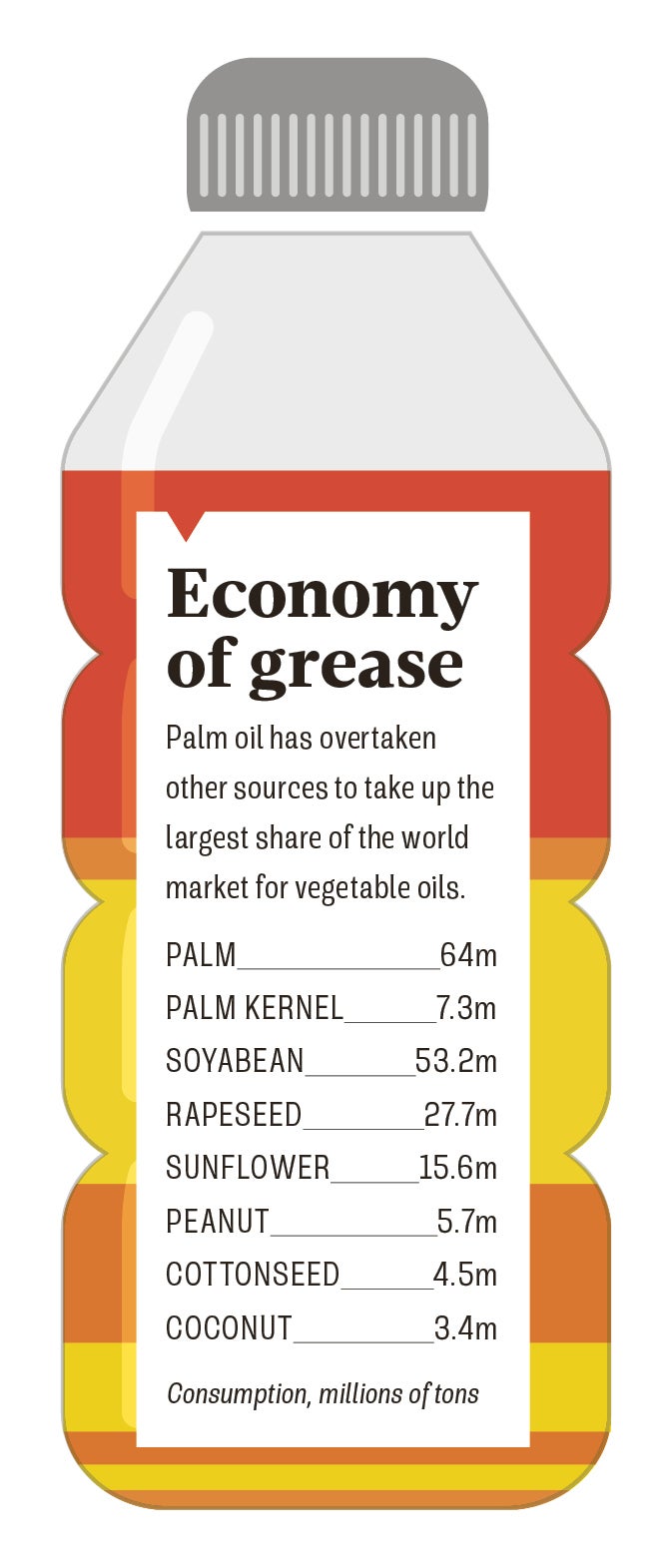

The output feeds a $60 billion market that is growing at more than 7 per cent per year. In 2014, demand for palm oil totalled over 70 million tonnes, around 65 per cent of which went into food. It is in chocolates, biscuits, ice cream, margarine, baked goods and spreads, as well as in cosmetics and hygiene products, from soaps to lipsticks – an estimated 50 per cent of all supermarket products contain it.

How it got to be there is a combination of technology, luck and social change. At the beginning of the 20th century, palm oil was a fairly small part of the global food supply. Originating in West Africa, it had been transplanted to Southeast Asia by European colonists, but was still principally eaten close to where it was grown. Unlike oilseeds, the palm fruit bunches – great bulbous, spiny things covered in red-orange buboes – must be processed within 24 hours of being picked, otherwise they go rancid.

Palm oil is derived from palm fruit

Infrastructure and mechanisation changed the calculus, allowing the fruit to go from tree to mill to market far faster.

Plantations started to expand, but palm oil was still at a disadvantage to its competitors. At the time, oils that were the byproduct of other industries – such as cottonseed – were cheap and plentiful, and animal fats, including whale oil, were still widely available.

Over the next quarter century, advances in chemical technology allowed producers to strip out many of the compounds within the oils that give them flavour, colour and odour, says Jonathan Robins, assistant professor of history at Michigan Technology University in the US, who has extensively researched the history of palm oil. “By the 1920s, they’ve got to the point where most oils and fats are basically interchangeable for things like soap and some edible markets,” he says. “But it’s really the 1960s and 1970s when palm oil really takes off and starts to appear in everything, and that’s really to do with the growth of this plantation industry.”

Botanists working in Southeast Asia made several breakthroughs in plant breeding in the middle years of the century, dramatically increasing the productivity of plantations, lowering the cost of producing palm oil and making it more competitive. Today, palm is the most efficient commercial oil crop, requiring considerably less cultivated area than rape, soya beans or others to produce a kilo of oil.

While the plantations were expanding, the consumer goods industry was changing. As the postwar food industry metamorphosed – or metastasised – into the vast packaged-goods empires that now dominate, it invested heavily in improving the taste, texture and shelf life of its products. That meant upping the doses of salt and sugar and introducing the high-fructose corn syrups that would hang heavy on the waistlines of a generation.

It also meant the widespread inclusion of hydrogenated oils, which improved the “mouthfeel” and longevity of packaged foods. Partial hydrogenation is a chemical process that breaks down some of the molecular bonds in the hydrocarbon chains that make up vegetable oil to make the substance solid at room temperature. It is the process that allows vegetable oil to be turned into margarine, replacing dairy fat.

Over the next few decades, hydrogenated oil was added to a huge range of products, from biscuits to ice creams, confectionery, even instant coffee and bread. It was used to coat chips, bulk out burgers and keep bread tasting fresh after weeks on the shelf. As cocoa butter became a fashionable and valuable addition to high-end cosmetics, chocolatiers began to use palm oil instead.

Palm oil – like more- expensive coconut oil –has the same properties as this hydrogenated oil. As the plantation industry in Southeast Asia grew, it gradually became more and more significant in the food supply – not because it was a necessity, but because it was an increasingly cheap way to make foods taste better for longer.

During the 1980s and 1990s, public health campaigns targeting saturated fats accelerated the use of hydrogenated oils. By the 2000s, though, those hydrogenated oils – otherwise known as trans-fats – were also linked to serious health issues. In 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration announced that there was no safe limit to trans-fat consumption, and began a total phase-out, which is due to be completed by 2018.

“Trans-fats were introduced inadvertently in the food supply in the process of trying to convert liquid oils – cottonseed oil and so on – into solid fats to compete with fats like coconut oil and palm oil,” Robins says. “Pulling out trans-fats means that they have to be replaced by other solid fats. And palm oil is its most readily available substitute.”

With few alternatives – other than drastically reformulating their products – the shift from trans-fats in the world’s largest consumer markets only embedded palm oil more deeply in the food chain. Supply and demand have become self-reinforcing. The US has historically relied on locally produced soya-bean oil, which is still by far its most commonly used vegetable oil. But since 2000, there has been a sixfold increase in US palm oil consumption. Over the same period, consumption in India, China and the EU has more than doubled.

So much of this has happened largely under the radar of consumers. In the US and the EU, relatively recent legislation means that palm oil has to be listed as an ingredient in food; before that, it was often not on the label, and manufacturers instead used ‘glycerin’, ‘stearic acid’, ‘palmitate’, ‘palmitic acid’, ‘sodium laureth sulphate’, or simply ‘vegetable oil’, among other terms. Industry bodies are still lobbying for that requirement to be relaxed. In other parts of the world, including China, India and Australia, palm oil can still be listed as ‘vegetable oil’.

Economy of grease - Palm oil in products

North Sumatra

Some of those who do know it’s there, don’t know why it matters. In seat 12C on SilkAir MI237 from Singapore to Medan, a young Dutchman is taking a holiday in Sumatra. It is, he says, a welcome break from his job, hooking up hoses to pump orange goo – unrefined palm oil – from the tankers and barges that pitch up every day in Rotterdam. “I know it’s bad,” he says, as the plane banks in over Legoland forests of palm trees arranged in straight rows. “But what’s the alternative? We like our cheap cookies.”

Medan, North Sumatra’s capital, is the palm oil capital of the world and the gateway to the state’s rainforests, which have, since the 1990s, been hacked back to make way for huge plantations. A few tourists do pass through, looking for the region’s few remaining charismatic megafauna – orang-utans, elephants, tigers and rhinos, all confined to dwindling patches of primary forest.

In Sumatra, there is four times as much land given over to palm plantations as there is remaining natural habitat for orang-utans, according to Panut Hadisiswoyo, whose 15-year mission, to protect the apes and their range has seen him and his NGO, the Orang-utan Information Centre, repeatedly butt up against the palm oil industry and its powerful backers. The business is intertwined with politics and money at all levels in Medan. Current and former politicians, police officials and military officers own plantations and mills; middlemen exert influence through cash or force, and at the ground level, farmers of all sizes – from major plantation owners to smallholders with a few hectares – rely on palm oil money.

“They consider the Leuser Ecosystem to be a barrier to development,” Hadisiswoyo says on the four-hour drive out of the city, along roads fringed with plantations – mainly palm, but some rubber left over from a previous boom, and a few orange groves. Closer to Leuser, acre upon acre of mangrove swamps is being drained and cultivated. “I say it again and again. The government just wants to bring in money for short term,” he says. “They only care about the money on the table.”

The encroachment of palm oil into this particular region of Sumatra could barely be more troubling. Not only is it on peatland, an ecologically significant and increasingly scarce environment; it is also at the southern gateway of the Leuser Ecosystem, a Unesco World Heritage site and one of the last relatively complete rainforests in Southeast Asia.

“A big part of the Leuser Ecosystem is untouched, compared to the rest of the forests in Sumatra, which have been fragmented,” says Jamal Gawi, the chairman of the Leuser International Foundation, which has worked with the government to try to conserve the area since the 1990s.

The ecosystem services from the region – the third-largest rainforest complex in the world – support more than four million people; it is the last place in Asia where the four large indigenous mammals – orang-utans, elephants, Sumatran rhinos and tigers – co-exist. And it is symbolically important, a monument to what is possible. “We could consider Leuser as a very optimistic place, which has a great future, if it is managed well,” Gawi says.

But it is not being managed well. In 2013, the sanctuary’s gazetted area was reduced from 100,000 hectares to 80,000, the remainder having already been lost to settlement and cultivation; another estimated 4,000 hectares has been lost to illegal clearance this year alone.

Reaching OIC’s field station on the northern edge of the Leuser Ecosystem means abandoning the car and submitting to a ball-breaking, thigh-straining ride through a plantation on motorbikes that squeal and slip along a part-flooded track that snakes through the palms, which stretch for miles either side in neat ranks. The path breaks out, finally, as the slope steepens into a perilous mudslide, lined on either side by young growth forest. At the top, a steel-framed watchtower, swaddled in plastic sheeting, overlooks a cluster of nurseries. By law, the field team should seek permission every time they pass through the plantation. Here, this is not enforced; elsewhere, the army or armed police keep trespassers out.

This 500-hectare patch has been reclaimed from illegal encroachment; it is a rare victory – an area of Sumatra that has been taken back and rehabilitated, something that some conservationists think is barely possible. Palm trees change the acidity of the soil around them, while the intensive use of pesticides and fertilisers further degrades the land.

Hadisiswoyo’s team have started from scratch, planting the basic building blocks of the rainforest. It is a slow and labour-

intensive process. This reclaimed land is a buffer between the advancing palm and the mist-draped primary forest behind it. The rehabilitation area is speckled with the charred trunks of lost forest giants, which were hauled away for timber down the same path that now serves the lodge. “Now it’s totally safe. It’s a good model for how to protect it,” Hadisiswoyo says. But it is an island.

A short drive away is what Hadisiswoyo calls the “ocean of palm oil”. It stretches on and on, further than the eye can see in every direction, one concession bleeding into another. Workers – predominantly women – lug bags of fertiliser off the tracks, wearing no visible safety equipment, the white lime dust caking their clothes and skin. Others – mainly men – move through the trees, harvesting the fruit with shears on long poles.

The “ocean” washes up at the boundary of the Leuser National Park. A thin orange mud track separates one from the other – in theory. On the park side there are wide bare patches and scattered areas of palm where the land has been stripped back for cultivation. Entering the boundary zone means going with a park ranger, because the area is “sensitive”, and Hadisiswoyo is keen to move on quickly. The “land mafia”, who he says are responsible for clearing the forest, and the tenants that have bought or occupied it, can be violent. Not far from here a ranger station was burned to the ground; OIC’s outposts have also been attacked and its staff threatened.

“This is a Unesco World Heritage site,” he says, his tone halfway between incredulity and anger. “A Unesco World Heritage site.”

The border is overlooked by the two smouldering towers of the mill, a huge facility that can take in hundreds of tonnes of raw fruit every day. Hadisiswoyo says that it is impossible to disassociate the illegal palm on one side of the path from the legal plantations on the other; he is convinced that it all ends up in the same supply chain and is driven by the same demand. “Big buyers must be responsible… They must be responsible, they must be careful about buying from the Leuser Ecosystem,” he says. “They accuse us of boycotting palm oil. We’re not boycotting it. We just advocate stopping its expansion. I’m not saying I’m OK with the palm oil. It’s already here. All we can do is protect what’s left.”

A land fire in Rimbo Panjang village, Kampar, Indonesia

Dirty business

Although there are other sources of destruction – roads, illegal logging and even a proposed geothermal energy development – it is oil palm that poses the biggest threat to Leuser’s survival. The crop, which is indigenous to West Africa, only grows in a narrow tropical band that, inconveniently, also contains the world’s last great rainforests. Malaysia and Indonesia came to dominate the business in part because the industry followed Sutton’s law – Why do you rob banks? Because that’s where the money is – but to a large degree it was the Asian governments’ willingness to make land available. Because the government had the monopoly on land and licensing, this new money became deeply intertwined with the politics of both countries, and it is now often difficult to see where government ends and business begins.

The opacity of the industry is a consequence of this blending of farm and state, and of a structure created by the same problem that constrained the expansion of the crop in the early 20th century – the fruit does not travel well. With just one day to get the fruit bunches from the tree to the mill, the industry has had to be fragmented and dispersed throughout the countryside. And it is: huge, high-sided trucks filled way past the brim rattle along incongruously small roads all across the island, heading for the mill.

Typically, a mill will buy palm from within a circle of less than 50km in radius. Although that whole circle may be one continuous monoculture of palm, the land beneath it is most often a patchwork of plantations owned by the mill, independent businesses that sell into it, and smallholdings.

I’m not saying I’m OK with the palm oil. It’s already here. All we can do is protect what’s left

Around 35-40 per cent of Indonesia’s palm oil is produced by smallholders – an estimated 1.5 million households. It is hard to get accurate numbers for how many mills are currently operating in Indonesia, but a widely quoted number is 2,500, ranging from huge, modern facilities run by multinational companies to ancient chugging machinery housed in tumbledown warehouses and sheds. It is at this point that the supply chain starts to blur. Although the multinationals often own large plantations, they cannot accumulate enough land to fulfil the needs of the global market, so they buy in additional supply from other mill owners.

Golden Agri Resources, one of the largest palm oil companies in the world, which aggregates the commodity upstream and sells it to multinational consumer goods companies, owns 44 mills in Indonesia, but buys from 489. Another, Wilmar, owns 35 mills and sources from more than 500.

This dispersed, decentralised structure – in which many middlemen and aggregators operate, buying fruit directly from small farms or oil from private mills – means that it is incredibly difficult to trace the final product back to its source. Sime Darby, which owns plantations and trades with mills in Malaysia and Indonesia, can trace 85 per cent of the crude palm oil it buys from third parties back to the mill, and 73 per cent back to the plantation. Wilmar says that it has 95 per cent traceability to its mills and refineries in Indonesia and Malaysia. Golden Agri Resources achieved full traceability to the mill last year, but not to the farm level. Further down the chain, a Nestlé spokesperson says that the company, one of the largest suppliers of consumer goods in the world, can trace 46 per cent of its palm oil back to the plantation, and 90 per cent back to the mill.

Consumers can, perhaps, be forgiven for not knowing what is in the products they buy; the industry doesn’t always know where the ingredient is coming from.

In that blind spot, very simple economics come into play. Wherever a mill springs up, there is an immediate incentive for local landowners to turn over their forests for palm oil, and smallholders will start to shift their production. Although Indonesia’s economy has grown rapidly over the past decade, an estimated 28 million people – nearly 11 per cent of the population – live below the international poverty line. Oil palm is seen as a quick route out of poverty, and for some it has been.

“It’s quite clear that you have these fantastic success cases in the villages, of people who arrived 20 years ago and are now able to put their children into higher education and so on. I would probably be doing the same thing,” says Yann Clough, a researcher at Lund University in Sweden, who, along with partners at the University of Göttingen in Germany, has extensively surveyed and studied smallholders in Indonesia. “There is really this pull, and this mechanism that you can leave your current status and make this big leap up the social ladder.”

Those smallholders essentially duck under the rules and standards expected of international businesses. They also don’t have the capital or knowledge to invest in better agronomy, meaning that expansion is their only option if they want to maintain their earnings as their plantations age and become less productive. Because the trees are hard to replace, and because the price of palm oil on international markets fluctuates, these smallholders have to keep adding more palm to stay afloat; they are just as locked into the system as their buyers.

As Arief Wijaya, an Indonesian forestry expert at the World Resources Institute, says: “We don’t have any idea how to control this smallholder expansion.”

Fixing palm oil

The Indonesian government is not deaf to international concerns about deforestation. But a government moratorium on licences for new palm plantations, announced by the president in April 2016, has had only limited impact, because those who are charged with enforcing it are often unable or unwilling to do so

Nurdiana Darus, Southeast Asia director for the Rainforest Alliance and a former minister in Indonesia, says that while she believes that the national government genuinely wants to fix its deforestation problem, it doesn’t have the reach to enforce its will on the ground. “It’s the willingness of the sub-national governments to do the enforcement,” she says. “They have either not bought into conserving the forests that they have left, or they’re just in it for the business.”

In Aceh for every ten cases of encroachment that NGOs reports, the police probably follow up on one. When conservationists met the new “owner” of the newly cleared land in Singkil, he was driving a car with red government plates. In North Sumatra, Hadisiswoyo has come into conflict with the land mafias, who come in and clear land on behalf of shadowy owners, who maintain plausible deniability if the police come calling. “If a supplier is burning, it’s hard to prosecute a big company. They keep their hands clean,” he says.

This tangled mess of middlemen operates between the big companies and the little guys on the ground – and outside the law. Even buyers with good intentions say that they often simply can’t tell beyond doubt whether the fruit has come from a certified plantation, or from the slash-and-burn clearance of a piece of protected land – although in a frank, not-for-attribution interview, one senior executive at a commodity trader says: “If you can trace it back to an oil mill, and you draw a 50km radius around that oil mill, you know where it’s coming from.”

But then, to try to track back the ownership of the mills is to jump down a Mossack Fonseca-esque rabbit hole of corporate obfuscation. Company directors may have side businesses; property is sometimes listed in the names of children or spouses. Some track back into investment trusts and funds in Malaysia and Singapore.

Priscillia Moulin, an investigator at Aidenvironment Asia, which performs detailed audits on the palm oil supply chain for businesses and governments, recalls trying to chase down the buyer of a concession that had been sold on by a large local company. “When we tried to trace back the owner, we found that the registered address was a wedding hall in Jakarta,” she says. Aid-environment concluded that the sale had not been legitimate, rather a way for the company to move a dubious asset off the books.

This all makes it very difficult for the companies charged with fixing the problem – a small number of big traders, such as

Wilmar, Golden Agri Resources, Musim Mas and Sime Darby. When the major consumer goods companies, such as Nestlé

or Unilever, made promises to stop all deforestation in their supply chains, it was these companies who were shoved into the limelight.

Today, almost all have well-oiled PR operations that can point to the wide range of sustainability activities that they sponsor on the ground. With a few exceptions, they respond to more-detailed requests for information with written statements studded with acronyms and the tangled non-language of corporate sustainability, which always seems devoid of any term that may imply commitment or responsibility – “incentivise”, “stakeholders”.

Privately – and occasionally publicly – they bemoan the fact that they are squeezed on all sides without any clear remedy. Government expects them to solve the problems in the supply chain, but does not enforce laws clearly; consumer goods companies – their clients – are wary of the public relations implications of being associated with deforestation, but push the responsibility for fixing it down to their suppliers.

“It’s a bit strange, when you get all of these commitments from [multinational consumer goods] companies, but they can’t control what they’re committing to,” says a senior executive at a top-tier trading company. “The elephant in the room is that no one is paying for the extra work that has to be done. The worst person is the consumer. The consumers expect the system to work properly. The brands try to push this responsibility on supply chain companies. Then, of course, we can’t push costs down to smallholders.”

Agus Purnomo, the head of sustainability at Golden Agri Resources says that clients are also unwilling to pay extra for sustainable palm oil: “They pay normal price, as low as it can get, and get the premium sustainability product in exchange. This is unfair, especially to the small growers.”

Raconteur contacted a list of the world’s largest buyers of palm oil, including Domino’s, Unilever, Nestlé, Johnson & Johnson and PepsiCo, to ask if they pay a premium on certified sustainable palm oil. Most simply pointed to their sustainability policies, which do not address the prices they pay to their suppliers. A PepsiCo spokesperson says that the company “[doesn’t] discuss the financials around our commodities for competitive reasons”. When pressed, a Nestlé spokesperson says that “in general” the company does pay a premium, but “we won’t be able to provide further details”. Others, including Unilever, Danone and Johnson & Johnson, did not respond to repeated queries.

Not every consumer will be responsible. But even if 25 per cent of consumers are, it will have an enormous and immediate effect on the markets

Bastian Sachet, the CEO of The Forest Trust, which has worked with a number of major consumer goods companies to reduce deforestation in their supply chains, believes that suppliers truly do want to improve.“They are stuck in between two things: the NGOs who beat on them constantly, saying: ‘you are not good enough, you are shit, you need to progress, etc’; and on the other side an overwhelming challenge of millions of smallholders, hundreds of mid-sized companies, a government that is not so positive over forest conservation,” he says.

There are no obvious solutions. The industry has tried certifying palm oil under a sustainable ‘brand’ – the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil – since 2004.

A voluntary association that certifies plantations based on a set of environmental and social criteria, it has had some high-profile successes – the Malaysian group, IOI, was effectively blacklisted by many consumer goods companies after it had its RSPO certification withdrawn in March 2016. Otherwise, it has failed to build momentum, with only a tiny fraction of producers actually signing up. It could even have been counterproductive

“We’ve even said that certification slows down transformation, because it makes people feel that they’ve addressed the problem, but they haven’t,” Sachet says. “When you look at the plantations that are certified, it’s mostly plantations that were already well run… it doesn’t address the deforestation.”

Sachet is surprisingly optimistic despite admitting: “I don’t think we’re losing this battle, but I don’t think we’re winning it either.” He believes that a global consciousness is beginning to emerge around this issue, and in the absence of any positive news coming out of the industry, consumers could move wholesale out of palm oil.

“What’s at stake for Indonesia is to make brand palm oil respectable, liked, accepted. To do that, you don’t do that with marketing. You do that by stopping the fires,” he says. “This is why the big companies are on board. They realise that if countries start to drop palm oil for food, the whole economy will collapse. It is a matter of survival for the government and the companies to make brand palm oil better. Otherwise, they’ll face the consequences.”

The warning tremors of that consumer revolt are already being felt. “Sans huile de palme” – ‘Without palm oil’ – stickers have started appearing on packets in France, which has experienced more active mobilisation on the issue than almost any other country. It has alarmed industry figures in Asia. The Malaysian palm oil industry is lobbying strongly at the EU for the labels to be banned on grounds that they are an unfair impediment to trade.

“I think it’s very, very simple to understand that bad production of palm oil destroys the forest. That’s not a complicated message,” says Erik Solberg, the new head of the United Nations Environment Programme. “Not every consumer will be responsible. But even if 25 per cent of consumers are, it will have an enormous and immediate effect on the markets.”

*some names have been changed to protect identities

The story of palm