The Tiananmen Square Museum is almost hidden on the fifth floor of a nondescript office building on Austin Lane, a narrow backstreet of strip clubs and grime-clogged air conditioning vents in Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong. On the ground floor, a security guard takes the names and ID card numbers of visitors; upstairs, the single-room office has been transformed into a maze of boards covered with densely packed text and photographs from June 4, 1989, when the People’s Liberation Army crushed demonstrators staging a pro-democracy sit-in in Beijing.

The museum is closing. After a long and costly legal battle, launched by the building’s management company and bankrolled by its freeholder, its founders have decided to sell their lease and raise money through crowdfunding to open another. Albert Ho, the chairman of the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, which maintains the memorial, is convinced the two-year campaign of harassment and expensive legal manoeuvring is motivated by the owner’s links to Beijing.

“This economic factor is, of course, a highly effective invisible hand in controlling and affecting people’s decisions,” Ho says.

The battle for the Tiananmen Square Museum, waged quietly and through commercial channels, is emblematic of a wider conflict over freedom, identity and rights in the Hong Kong ‘Special Administrative Region’, two decades after it returned to Chinese rule. The principle of ‘one country, two systems’ espoused at handover has been eroded, gradually at first but now with frightening speed, as the economic interests of the SAR’s elite — whose wealth is increasingly contingent on cross-border interests — meshes with Beijing’s belief in the sovereignty of ‘One China’.

“One country, two systems is being sold out by the economic interests of the businessmen, or any party who wants money,” says Lee Cheuk-yan, a veteran Labour Party politician, general secretary of the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions and the secretary of the Hong Kong Alliance. “Money is what sells out Hong Kong. If anyone is looking for money, they look to China.”

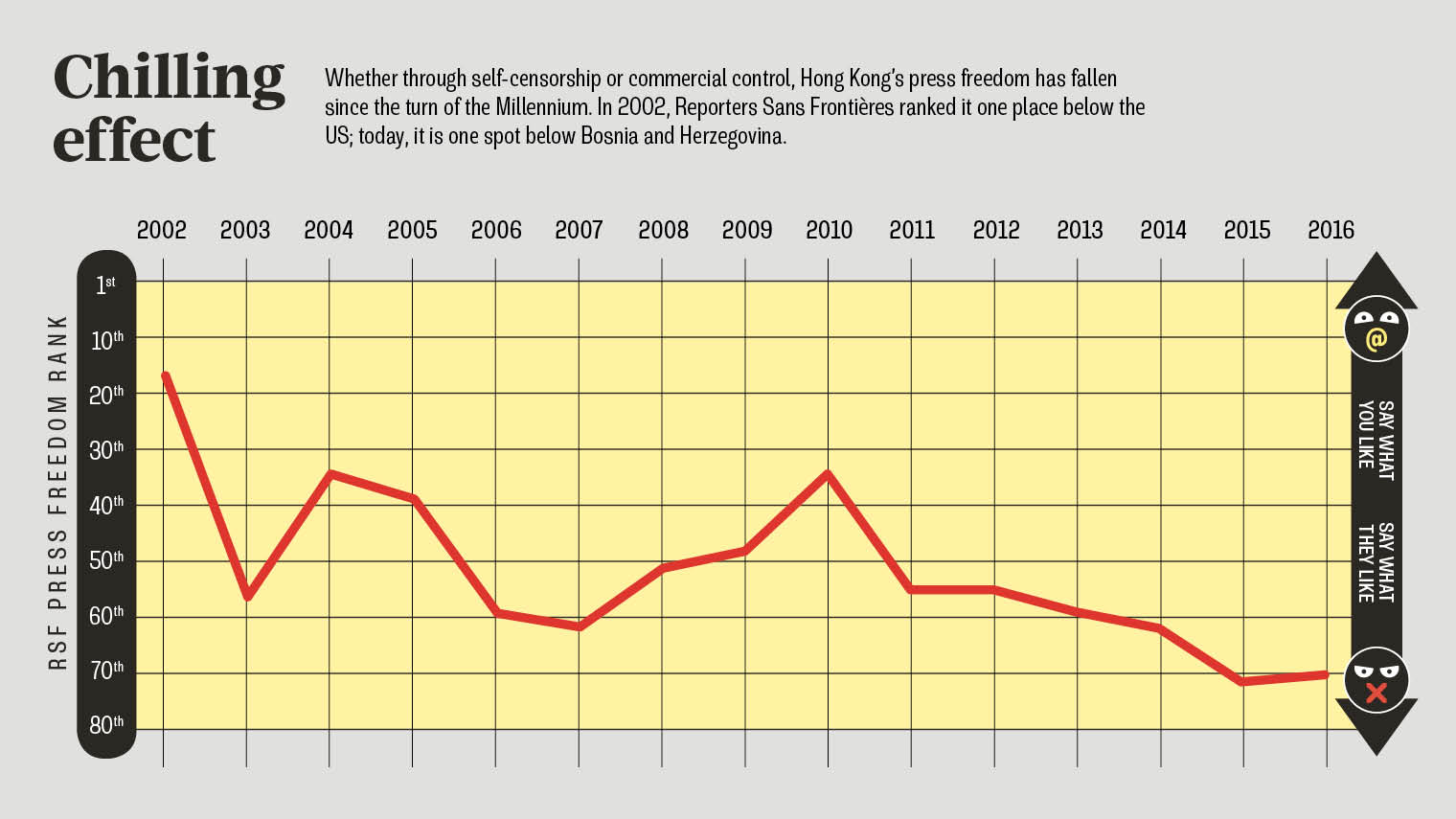

This selling of the city includes the increasing ownership of the media by mainland interests, both Lee and Ho say. Even the South China Morning Post, the iconic century-old newspaper, was bought by the Chinese e-commerce group Alibaba in 2015. An investigation by the campaign group Reporters Sans Frontières, published in April, found that more than half of Hong Kong’s media owners have been appointed to influential political bodies in China.

Lee Cheuk-yan

In April, Keung Kwok-yuen, an editor at the Ming Pao newspaper, was sacked after the paper reported on politicians and businesspeople implicated by the Panama Papers data leaks.

Media tycoon Jimmy Lai, whose Cantonese language newspaper Apple Daily has supported the pro democracy movement since its founding in 1995, has been harassed by pro-Beijing activists, his house has been firebombed, and advertisers wary of Beijing have pulled out of his titles. The combined social and commercial squeeze is having a chilling effect on free speech, according to activists and journalists.

“It’s about the gradual erosion of freedom in Hong Kong,” Lee says. “And the reason is, we don’t have democracy to protect our freedom. If the people of Hong Kong stick together, we can fight back. But what makes… our efforts futile, is those who sell out Hong Kong because of money.”

The fears of many activists were crystallised earlier this year when the Hong Kong publisher and British citizen Lee Bo, who went missing in late 2015, appeared months later in mainland China. He had apparently been taken in Hong Kong by Chinese security agents in a major breach of Hong Kong’s judicial independence. His company, Mighty Current, published books critical of the Chinese leadership. Lee made a statement on Chinese television saying that he had voluntarily gone to the mainland; those who know him insist it was a forced confession.

If Lee Bo was, as many activists — and the UK government — believe, abducted by the mainland, then Beijing crossed a line, fundamentally undermining the ‘one country, two systems’ principle. “I see this as part of systematic ‘institutional capture’ by Beijing,” says Surya Deva, associate professor in law at the City University of Hong Kong. “All institutions and actors which may cause any potential threat to Chinese interests are being managed. Different tools are used — taking over of media companies; strategic non-appointments or appointments; abductions — but the goal is to neutralise such elements.”

RUNNING SCARED

Bao Pu, tall and round-shouldered, wears a unshifting hangdog expression and talks with a matter-of-fact fatalism. “I don’t ever believe that the Hong Kong police will protect me.” he says as he marches through the glittering subterranean corridors of Central’s high-class Landmark shopping mall. “If the mainland security tried to kidnap me, I wouldn’t have protection. I wouldn’t trust the Hong Kong government to do anything. That’s the situation.”

Bao, like Lee Bo, is a publisher of non-fiction books about China, sold to the local market and to curious mainlanders willing to risk taking them home. “The Communist Party created my market,” he says. He has found, like the Hong Kong Alliance, that he is being commercially squeezed. He has struggled to find printers willing to take on his books; everyone is worried about losing their ability to do business over the border, being kicked out by their landlords, or becoming the next Lee Bo.

So many people in Hong Kong, he says, pointing to the customers in the mall’s cafés, have been dulled by the appearance of stability and success and have not registered how fast their rights have withered.

“Most of the people comply. Most people do not protest. Most people choose to ignore this kind of matter. And guess what? The situation will get worse.”

Those who do put their heads above the parapet face overwhelming odds, Bao says.

“They have nothing but their bare hands. Think about it. What’s on the other side? It’s comical. On the other side are a large group of indifferent Hong Kong residents. They see trouble. They don’t want trouble. Behind them are the Hong Kong elites busy selling out Hong Kong interests.”

UMBRELLA MOVEMENT

The issue of who picks Hong Kong’s chief executive has been a thorny one since the handover from UK rule in 1997. The Basic Law, which enshrines the rights of freedom of speech and association in Hong Kong, also says that the election of the head of government and the legislature should be by universal suffrage. Under the current system, however, a committee of 1,200 members

appoints the chief executive, while local representatives are elected by a direct vote.

Since 2013, the SAR has been debating reforms to this electoral system, with the pro-democracy movement campaigning for a free and open vote. In August 2014,the National People’s Congress Standing Committee in Beijing, China’s top decision making body, quashed any hope of true universal suffrage, and the following month, thousands of people took to the streets. What started out as a non-violent sit-in, Occupy Central With Love And Peace, turned into a massive movement of strikes and protest, with its symbol the Umbrella used to defend against teargas.

Many young people turned out, mobilised by the Hong Kong Federation of Students and the pro-democracy student group Scholarism, whose leader Joshua Wong became the international face of the Umbrella Movement.

The chief executive, Leung Chun-ying — known as CY Leung — struggled to respond to the outpouring of anti-government sentiment, refusing to meet protestors. The sight of police officers teargassing and beating students undermined the trust that many in Hong Kong had for their institutions. Attacks on young protestors by pro-Beijing mobs went largely unpunished, and many people began to fear for the rule of law in the SAR.

Demonstration against the arrest of protest marshalls by police in November 2014

By December 2014, the protests had simmered down and the sites had been cleared. Police patrols prevented any further occupation. Since then, Occupy and the Umbrella Movement have fragmented into a kaleidoscope of pressure groups and political parties. Some have kept up protests. In April, around 1,500 people gathered at Hong Kong’s international airport, after reports in Jimmy Lai’s pro-democracy newspaper Apple Daily that the chief executive’s daughter had used her father’s influence to skirt security rules - claims that CY Leung denies.

Among the organisers of the protest was Wilson Leung, a young barrister who is part of a group of lawyers that is trying to maintain the pressure post-Occupy and, in his words: “spread these messages amongst the public in a rational, reasoned manner.” Like many other activists in Hong Kong, he wears a faint hue of fatalism. “Does [protest] change anything? I think it might,” he says. “It’s hard to know what’s in [CY Leung’s] mind, and harder to know what’s in the mind of the central government.

“There’s no magic bullet. You do whatever you can and hope that with enough pressure, something will happen. But we know from other countries that it can’t happen overnight. South Africa, Korea, Taiwan. A lot of little things that individually make no difference. But cumulatively…” he tails off.

As a barrister, Wilson Leung has relatively free rein to involve himself in politics; his counterparts in big firms do not have the same luxury. The same chilling effect that has impacted the media and corporate property is at play in the jobs market for young people, he says. “It varies from industry to industry, but there’s pressure in a lot of them, because of the increasing integration with mainland China. If you’re in a big-four accountancy firm, it’s very difficult to participate in any politics that is contrary to the government’s position.” That makes it hard for young people to put their heads above the parapet. As he says: “It’s a big sacrifice. That’s why I really admire all the young people who are trying to come out and do something politically. A lot of them will find it really difficult to get a job in the commercial sector.”

That, combined with a degree of apathy amongst more comfortable strata of Hong Kong society, means that the debate has also become more polarised, and spawned more extreme views, including a resurgent ‘indigenisation’ movement, led by groups that have morphed into political parties, including Hong Kong Indigenous and Youngspiration.

INDIGENISATION

Some factions that emerged from the peaceful movement have adopted more aggressive direct action. An attempt to evict unlicensed fishball hawkers from the shopping hub of Mong Kok, in

Kowloon, on Chinese New Year in February led to an outbreak of civil disobedience — opponents call it rioting.

The indigenisation movement portrayed the crackdown on the fishball stalls — which was ostensibly for reasons of health and safety — as a Beijing-sponsored attack on local culture. Around 60 people were arrested during the civil disobedience. Among them was Ray Wong Toi-yeung, the leader of Hong Kong Indigenous, who posted a defiant ‘final message’ on Facebook before the police broke into the apartment where he was laying low. “Rather be a shattered vase of jade,” he said, “than an unbroken piece of pottery.”

The aftermath of police clashes with pro-democracy protesters outside government headquarters in December 2014

Fears that the SAR’s identity and culture will be diluted have fed the nativist movement, which is increasingly bold in its calls for independence. Even those outside of the radical secessionist movements fret that the defining characteristics of Hong Kong are disappearing. The Cantonese language is still dominant, but Putonghua — ‘standard’ Chinese — is creeping in.

The Occupation lasted 79 days, but it was a total failure. We were back to square one at the end. We didn’t get anything

“Since the return of Hong Kong to Chinese hands in 1997… [the Chinese government] has tried to strangulate different segments of Hong Kong,” says Kenny Wong, one of Youngspiration’s founders. “We can see that the Chinese government is using various measures to undermine Hong Kong’s values bit-by-bit, by promoting Putonghua, by using simplified Chinese, by trying to undermine the rule of law… Not only our cultural identity, but our system is being broken down bit-by-bit.” Wong, along with several of his co-founders, are running for seats in Hong Kong’s legislative council in September’s elections in order “to fight our way back into the system”. He is sanguine about whether they can change anything within the political machine, but says that getting on to the legislative council will give Youngspiration resources, media airtime and a platform to spread its ideas. It could be the best of a dwindling number of options.

“The Occupation lasted 79 days, but it was a total failure. We were back to square one at the end. We didn’t get anything,” Wong says. Although he laughs off the idea that the Chinese New Year clashes were riots, and says that Youngspiration is more focused on social projects, he adds: “I think

Hong Kongers are being more open-minded these days. They have a higher tolerance for direct action.”

The nightly protests that paralysed Mong Kok earlier in the year have dwindled, and the area has gone back to seed; a riot of pulsing neon and steam from griddle plates. The fishball hawker stalls have gone too. The relative calm is likely to be temporary, however, as Beijing’s intransigence looms over locals’ hopes for change — what several activists refer to as “eggs against the hard, high walls”, a paraphrasing of a quote by the Japanese writer Haruki Murakami: “If there is a hard, high wall and an egg that breaks against it, no matter how right the wall or how wrong the egg, I will stand on the side of the egg.”

“If you’re not going to open [the political process], there’s no hope. If there’s no hope, then people will be angry, and they will want to vent their anger against the government,” says the Labour Party’s Lee Cheukyan. “Their only way out is for them to take seriously our aspiration for real democracy in Hong Kong. If they don’t do that, the fight will go on, the young people will get more

radical, the whole country will get more angry and more hopeless.”

Illustration: Matt Ward

PHOTOS: KEVIN FRAYER/GETTY IMAGES; PHILIPPE LOPEZ/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

RUNNING SCARED

UMBRELLA MOVEMENT