“Be alert, but not alarmed” was the advice given to churches by the Metropolitan Police in July, after the murder of an 86-year old Catholic priest, Father Jacques Hammel, in Normandy. It was the second attack in France in two weeks, coming so soon after 84 people were killed during Bastille Day celebrations in Nice.

July has been a bloody month in Europe. Three separate incidents in Germany – one with an axe, one with a gun and the third with a bomb – killed nine people and wounded dozen. Two of the attackers claimed allegiance to the so-called Islamic State, one directly referenced the 2011 massacre by the Norwegian white supremacist Anders Behring Breivik.

European governments are struggling to reassure the public that they are able to keep a lid on what appears to be a worsening problem with violent religious and political extremism. In response to the events in Nice, France extended its state of emergency, put in place after attacks in Paris in November 2015, giving the security services increased powers of arrest and detention. In the UK, the government has pushed through the Investigatory Powers Bill, legislation which gives authorities more latitude to intercept and hack communications.

But experts warn that these sweeping measures may do little to contain the risk of lone actor, or “lone wolf” attacks. The fingerprints that terrorists used to leave behind as they tried to move or source guns or explosives, position operatives, are far fainter when their weapons are a knife, an axe or a truck. Security services are adapting to new channels of radicalisation and terrorist inspiration online, but the sheer volume of material available above and below the waterline of the mainstream and ‘dark’ web means that almost anyone, anywhere, can view it.

It is a much more difficult thing to stop. How many people do you have to get involved when you just decide to go and buy or use your own van and mow people over?

Mohamed Lahouaiej-Bouhlel, who drove a truck through a crowd celebrating Bastille Day in Nice this July, was apparently radicalised in a matter of weeks, morphing swiftly and silently from a promiscuous, drug-taking and largely secular young man into a mass murderer.

“[Lahouaiej-Bouhlel] is a nightmare, because he wouldn’t have flashed up on any counter-terrorism [lists]. He wouldn’t have been under surveillance or anything of that nature,” says Chris Phillips, the former head of the UK’s National Counter Terrorism Security Office.

The UK’s security services, perhaps more so than their counterparts in France and Belgium, have developed a solid system of intelligence gathering and sharing that has meant few serious threats have as yet slipped through the gaps, but there are known to be at least 2,000 individuals that the security forces have identified as potential terrorists; only a small number are under constant surveillance.

Banksy’s graffiti art appeared on the side of a house in Cheltenham portraying an era where everyone is being listened to. The artwork is just a few miles away from Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), (Photo by Matt Cardy/Getty Images)

“We’ve been reasonably successful over here in defeating plots before they get to the point of killing people. But we can’t guarantee that’s going to go on. We’ve got a very tried and trusted intelligence network that works quite well. We’ve funnelled intelligence from all of the different agencies from one point, which helps us to be more effective and not miss stuff,” Phillips says.

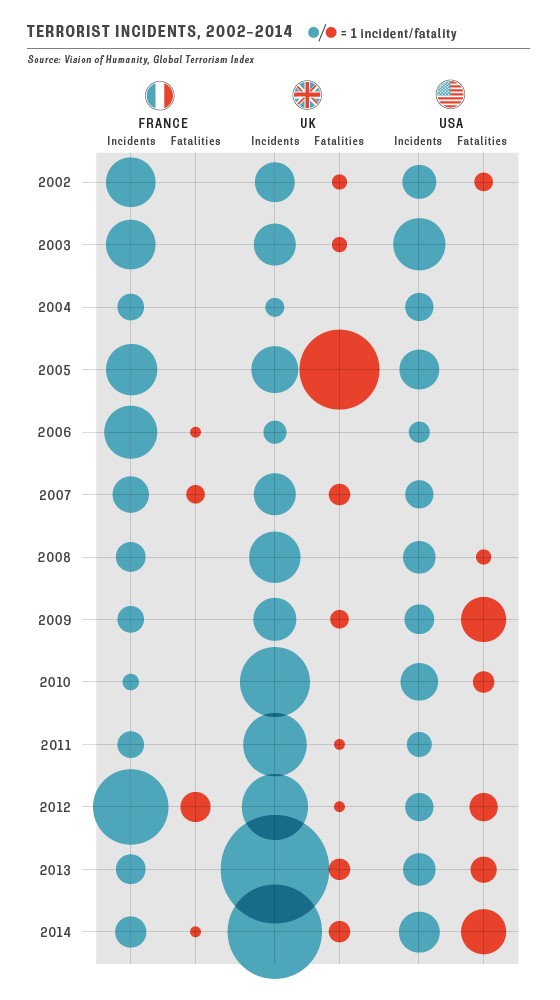

The problem with self-radicalised lone actors is that they do not trigger the same warnings as organised conspiracies. According to the Institute of Economics and Peace, which compiles the Global Terrorism Index, 70 per cent of all terrorism-related deaths in the West between 2004 and 2014 were perpetrated by ‘lone wolf’ attackers – most of those were political, rather than religious extremists.

“It is a much more difficult thing to stop. How many people do you have to get involved when you just decide to go and buy or use your own van and mow people over?” Phillips says. “Intelligence is unlikely to be able to deal with that too well, because they’re not likely to be involved in a plot where informants come in, or we’re picking up communications. That’s not happening, because they don’t need to. They just get in a car and drive.”

Prevent

Against this backdrop, more surveillance or security powers are unlikely to solve the problem.

“The easy, knee-jerk response to every incident is to demand security… I think it’s an easy option. It can create a sense of undue alarm amongst the public. Seeing armed police everywhere can be just as counterproductive,” says Bill Durodié, chair of international relations at the University of Bath and an expert in the social impacts of terrorism.

“But more importantly, I think it avoids asking the deeper questions. You can’t solve a social problem with a security solution. In my opinion, we’re looking at a very different problem to that which security agencies are trained to deal with and confront.”

Identifying individuals vulnerable to radicalisation is complex, and relies on a combination of traditional intelligence, community policing and, perhaps most importantly, the complicity of communities. In the UK, the Prevent strategy, which relies in part on schools, universities and community groups to pass on information, has been widely criticised for its apparent chilling effect on civil liberties, and for being ineffectual in actually generating referrals.

Two UN officials – Ben Emmerson, the special rapporteur on on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, and Maina Kiai, the special rapporteur on the right to freedom of assembly – have openly criticised the scheme. Teachers and lecturers have hit out at the expectation that they should inform on their students.

“It’s also been perceived as spying on students, schoolchildren, individuals in the Muslim community, because the early strategies were looking at violent extremism linked to that Islamist narrative,” says David Lowe, a former member of the anti-terror unit at the UK’s Special Branch, who now teaches at Liverpool John Moores University.

“It was doing their best to try and deal with an issue. But it was targeting Muslim communities, and it had the adverse effect of alienating Muslim communities here and in other European states as well. The Dutch one had similar problems.”

Lowe works with Merseyside Police on their implementation of Prevent, and says that despite its bad press and a certain lack of sensitivity in its execution, it is founded in the right mix of community policing and social services. He suggests that the Home Office should admit that it made mistakes and rebrand the programme.

“Get it rebranded, it’s a multi-agency approach, it’s pre-criminal, it’s about helping individuals who are vulnerable to being drawn to extremism and terrorism and trying to help them not go down that path. We have to take that positive attitude… This is a long-term strategy, but what do we do in the meantime?”

Social challenge

For Durodié, though, there is a deeper, more troubling problem that goes well beyond the immediate issues that Prevent is trying to address. Successive British leaders have been very poor at creating a strong counter-narrative against radicalising influences.

“I detect a deep insecurity amongst the authorities that prevents them from articulating what they should be articulating about the society that we want,” he says.

The solution, though, is not to try to predict who’s going to tip over, and I find it very unfortunate that that’s where all the resource is going, into prediction through our Tesco Clubcard purchasing patterns

“The authorities often talk about sudden conversion, and that’s simply because they don’t understand the much slower process of disengagement, self-distancing and growing rage that goes on beneath the surface… It’s a difficult debate to have… Of course individuals who perpetrate acts of terror are responsible for their actions, but at the same time, I do think we have to understand that every individual in society is a product of that society.”

Alongside the alienation and disenfranchisement that many young people feel, there has been a reluctance to openly challenge transgressive views from across the political and religious spectrum.

“The solution, though, is not to try to predict who’s going to tip over, and I find it very unfortunate that that’s where all the resource is going, into prediction through our Tesco Clubcard purchasing patterns – you know, if you hire me, I’ll be able to predict who’s going to become radicalised,” Durodié says.

“The point is that extremism is the extreme expression of mainstream problems, and if you want to reduce extremism, you need to address the mainstream, not find the extremists. What’s wrong in the mainstream that allows people at the margins to go completely off the rails?”