Photo: Bénédicte Desrus

Sitting in the waiting room of the Ángeles hospital in Mexico City’s up-and-coming Escandón neighbourhood, Alejandra Olivo cannot help dozing off, regularly jolted awake as her body slips from side to side in her small red chair.

The 35-year-old mother of one is about to have her first consultation with a dietician — at 145cm (4’ 9’’) tall, she weighs about 105kg (16.5st). Sleep woes, headaches and joint pains have become a constant feature of daily life. Once an avid salsa dancer, she stopped going to the local salón years ago, as she couldn’t cope looking at her reflection. Even walking short distances has become onerous.

It’s not the first time she has tried to lose weight. “My father is worried about me,” Olivo tells the nutritionist, before pausing for a moment, “and my daughter needs me.” In the course of the 90-minute session, she finds out her weight is twice what it should be. The path to a healthier life will be long and some blood tests must be done to check for any complications, such as diabetes.

Alejandra is the youngest of 22 brothers and sisters – same father, different mothers. All of the children have weight problems. Both her parents are clinically obese and diabetic, with the string of typical complications, including hypertension and poor circulation. This is hardly unique. Mexico is experiencing an obesity epidemic. Last year, it snatched the title of the world’s fattest country from its neighbour to the north.

Like the Olivos, more than 70 per cent of Mexicans are either obese or overweight. Kids are particularly at risk, with a third of two- to eighteen-year-olds affected, some 5.6 million people.

The problem is only getting worse. Between 1988 and 2012, obesity rates skyrocketed from 9 per cent to 35 per cent. Recent studies suggest that as much as 15 per cent of the population has type 2 diabetes, the highest in any of the 34 countries of the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development. Four million Mexicans are thought to be unaware they are living with diabetes — healthcare professionals call it the “silent killer”.

“Having a sick population can have a direct impact on the economy and the productivity of the country,” says Juan Rivera Dommarco, founder of the nutrition and health investigating unit at Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health. The government estimated that in 2017 obesity would cost the country between £7.3 billion and £9.7 billion if no action was taken. “But it’s not just the economic cost, it’s all the human tragedy, all the cases of diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, amputations, that keep growing,” Dommarco says.

A leader in the prevention of obesity in the country, the Cornell University graduate says he worries for the younger generation. “We already have a third of our youth population either obese or overweight, which will bring illnesses at very early and productive stages of their lives.”

24-hour eating

From dawn to dark, Mexico’s signature street food carts provide a quick and easy option for a meal or a snack. Classic antojitos, “little cravings”, include esquites, a little corn-cup filled with lime juice, chilli and mayonnaise — beef and bone marrow-infused versions also exist — crisps in a bag filled with hot sauce and mayonnaise, known as “dorilocos” and meat consommés.

Among the wide range of tacos on show, the most popular include carnitas, or “little meats”, where the pork is simmered in lard until tender; the slow-cooked mutton barbacoa; the al pastor, a not-so-distant cousin of the shawarma and Turkish doner kebabs; and the tacos de cabeza, or head parts, such as beef or sheep’s tongue, eyes, ears and brain. Quesadillas, a soft corn tortilla with melted cheese, usually include filings of mushrooms, courgette flowers, huitlacoche — corn fungus — or meats. Beans and rice are also central to Mexican cuisine.

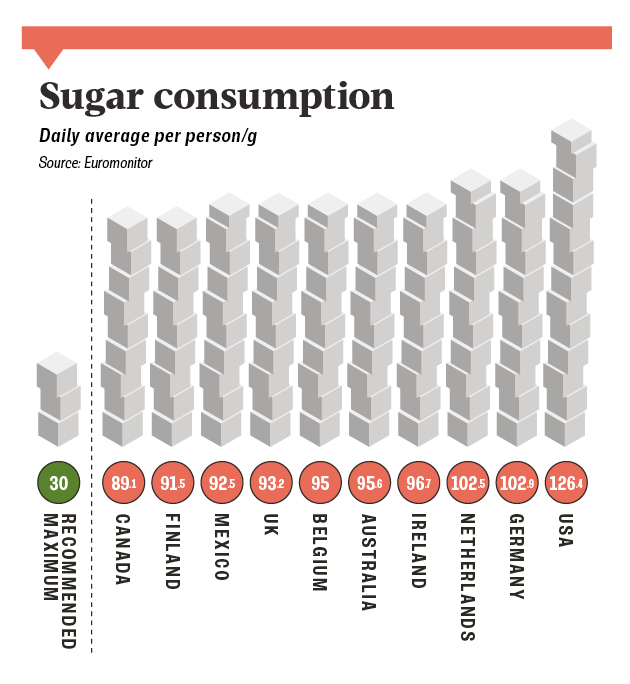

Mexico is by far the world’s number-one consumer of Coca-Cola, on average drinking 728 Coke beverages per person, per year

What better than to wash it down with than a fizzy drink? Mexico is by far the world’s number-one consumer of Coca-Cola, on average drinking 728 Coke beverages per person, per year — almost twice as much as the second-place USA.

People often have their first sugar fix early in the morning with breakfast, drinking steadily throughout the day until bedtime. Alejandra Olivo is no different. When she worked with her mother at a burger joint in the Mixcoac neighbourhood of Mexico City, she would wake up around 7am, get to work, and start drinking her daily 600ml or litre bottle of Coca-Cola from around 9am.

“It’s like a drug, it’s an addiction,” says her father, Faustino Olivo, who runs the family’s restaurant, El Mesón de Olivo.

In Mexico, Coca-Cola is more than just a drink. It is iconic. At the village of San Juan Chamula, in the southern state of Chiapas, it is even part of religious rituals. In the white and blue church, Christian worshippers, inspired by their Mayan ancestors’ traditions, use candles for incantations and prayers, spoken in tongues, sacrifice chickens to keep death at bay, and use Coca-Cola to burp and cleanse the body of evil spirits.

Cheap and easy street food is a national obsession. Photo: Jacobo Zanella/Getty Images

When US researcher Susan Bridle-Fitzpatrick arrived at Mazatlán, in the north-western state of Sinaloa, in 2011 to begin her study on food access, the “domestic creativity” of street food is what grabbed her attention first. “What absolutely struck me was the inundation of sugary soft drinks and packaged snacks,” she recalls.

An adjunct faculty at the University of Denver, she spent 11 months in Mexico studying people’s access to food. Fresh fruit and vegetables are usually easy to come by in numerous local and itinerant markets, even for low-income families. But although access is relatively good, the over-exposure to unhealthy products outweighs by far the benefits of traditional Mexican healthy food, she says.

For Gonzalo Alemán Ortiz, a specialist in internal medicine, it is not just about the food. “First you have the bad product, then the excessive quantity and what follows is physical inactivity,” he says. “It’s a fatal combination.”

Studies have shown that a sedentary lifestyle is widespread across the country. In 2013, a government report showed that nearly 60 per cent of children aged 10 to 14 years-old had not participated in any organised sporting activity in the 12 months prior to the survey. In the 25 to 29 year-old range, only 15 per cent had exercised.

Treatment is also a major problem, as most patients tend to wait a long time before seeking medical help and find out that they suffer from diabetes late in the process. “At the beginning it doesn’t hurt, so they let things be,” Alemán says. “By the time they get here, the damage already done is very hard to reverse.”

The industry fights back

Coca-Cola was first introduced to Mexico in 1926, as the country was reeling from a bloody revolution that killed or injured about a tenth of its population. Over its 90 years in Mexico, the company has built a remarkable distribution network.

In a country that spans over 1.9 million square kilometres, about eight times the size of the UK, with dense mountainous regions and inhospitable deserts that spread from one border to another, the famous red trucks are able to fill up stocks of fizzy drinks in even the most forgotten areas. A trip down the sinuous roads of Chiapas state, one of the most cut-off areas in the country, provides one of the many testimonies to Coca-Cola’s hegemony.

On the side of the roads, colourful paintings of the brand often cover the walls of small shops. For a long time, a bottle of Coke was often cheaper than water, in a country where tap water is largely undrinkable.

The system is so good that it has attracted the attention of the Mexican government, which on various occasions has teamed up with the company to take advantage of its distribution network. In 2007, the forestry commission partnered with Coca-Cola to plant 30 million trees in deforested areas. The company provided funds, and Coca-Cola trucks transported trees throughout the country.

As with any business, Coca-Cola has interests to protect. In Mexico, its biggest market after the US, the stakes are high. Teaming up with government agencies on environmental, educational or health projects has its perks. The ties are deep: Coca-Cola’s former chief executive for Mexico, Vicente Fox, was elected president in 2000.

However, the government has begun pushing back. In 2013, Congress passed a 10 per cent tax on sugary drinks, and a further 8 per cent tax on junk food. Early results show that the levy is proving to be efficient and could inspire other countries to follow suit.

Sugary drinks such as Coca-Cola are sold widely across Mexico. Photo: Susana Gonzalez/Bloomberg via Getty Images

In only a year, purchases of taxed beverages had gone down 6 per cent, reaching 12 per cent in December 2014, according to a study published in the British Medical Journal. Like others, Coca-Cola has reported slightly reduced profits from its operations in Mexico.

The drinks giant has vowed to fight these changes. In July 2014, seven months after its implementation, the company responded with a colossal £5.6 billion investment plan for Mexico to promote physical activity and “continue expanding [its] beverage portfolio”.

Coca-Cola is also moving behind the scenes. Far from being set in stone, the sugar tax is at risk of being cut down every year, when Congress votes on the fiscal package it is part of. In Mexico, big companies often go through powerful industrial chambers to carry out their most strategic lobbying with the government, says Luis Manuel Encarnación, director of the Mídete Foundation, a lobbying watchdog in the industry.

“We know that they [the chambers] approached the finance ministry directly to negotiate a tax decrease,” he says, “they met with lawmakers and several political parties, so they wouldn’t interfere with efforts to lower the tax.” Last year, in its first year of existence, the same lower chamber that had passed the tax a few months before voted in favour of a reduction. The motion was blocked Sin the senate, but Encarnación has no doubt that the lobbyists will keep the pressure on into the next cycle of negotiations, and beyond.

In the USA, Coca-Cola spent $21.8 million (£15.4 million) on research and $96.8 million on partnerships with health organisations between 2010 and 2015

The food and beverage industry is known to work with a wide range of health experts, from academics to journalists, and to finance its own studies, which are then presented in medical conferences and sent to lawmakers. In a recent forum about obesity and the sugar tax in Mexico, economists presented studies to the national medical academy portraying the tax as “counter-productive” and harmful to the economy. The data their studies were based on were provided by the industry itself.

In the USA alone, Coca-Cola spent $21.8 million (£15.4 million) on research and $96.8 million on partnerships with health organisations between 2010 and 2015, the firm says. In August 2015, The New York Times revealed that a further $2.1 million was spent on travel grants, related expenses and professional fees for health experts the company works with. Those same experts would then go on to publicly promote Coca-Cola’s mini-cans as healthy snack food.

The industry has consistently tried to undermine the validity of the link between obesity and sugar consumption. A 2011 study funded by The Coca-Cola Company and published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition concluded that the quality of scientific reviews on sugar-sweetened beverages and health problems, such as obesity, were poorly researched. Documents from Coca-Cola show the firm spent $319,500 between 2010 and 2014 on research led by one of the study’s authors, Dr Michelle Althuis.

Joan Prats, vice-president for corporate affairs and communications at Coca-Cola Mexico, declined to comment on payments to health experts. In an emailed response to questions, he said: “The excise tax on sugar-sweetened drinks in Mexico has been ineffective in terms of combating the nation’s overweight and obesity rates. Obesity is a complex issue, and no one food product or beverage can be blamed as the sole contributor to the problem… The country does not need to engage in populism on an important matter, such as people’s health. We need to work on concrete and explicit actions, making people’s wellness a real priority.”

In the meantime, the human cost of Mexico’s addiction to sugar and fat continues to grow. Back at the Ángeles hospital, Alejandra Olivo met with her nutritionist for the second time. She brought her medical results with her. Diabetes is the only word she remembers from the doctor’s speech.

She knows it is not a death sentence, but she also understands carnitas, barbacoa, and full-sugar Coca-Cola are out. “It’s very hard but I’ve asked them not to let me let go of the programme,” she says, “because within the next six months, I’m going dancing.”

Osborne’s sugar tax

Osborne’s sugar tax is aimed at improving diets. Photo: WPA Pool/Getty Images

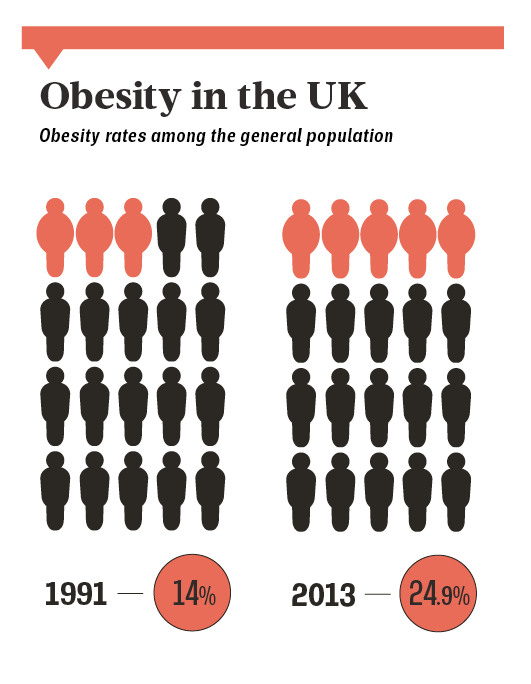

One of the surprise additions to chancellor George Osborne’s 2016 budget was the announcement that drinks with a high sugar content would be taxed at between 18-24p per litre.

It is a good start, says Graham MacGregor, chairman of the pressure group Action on Sugar and professor of cardiovascular medicine at the Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine in London. Such a tax can have an impact, he says, but it is not as effective as regulating the amount of sugar in food and drink by setting time-bound targets, a tactic that worked with salt.

“You set targets for reduction, 10, 20 per cent reduction over a time course. You slowly screw them down… We reckon we could reduce sugar intake in the UK by about 50 per cent by doing that. [It would be better] if you did other things, such as stopping advertising of these unhealthy products to children — if we ban cigarette advertising, why don’t we ban unhealthy food, it’s a much bigger cause of death.”

MacGregor, who has championed the subject worldwide, says that tackling dietary diseases is possible, because people’s tastes are mutable, and can quickly adapt. The challenge is one of political courage.

“The problem is, you need someone who’s willing to confront the food and sugar-sweetened soft drink industry,” he says.