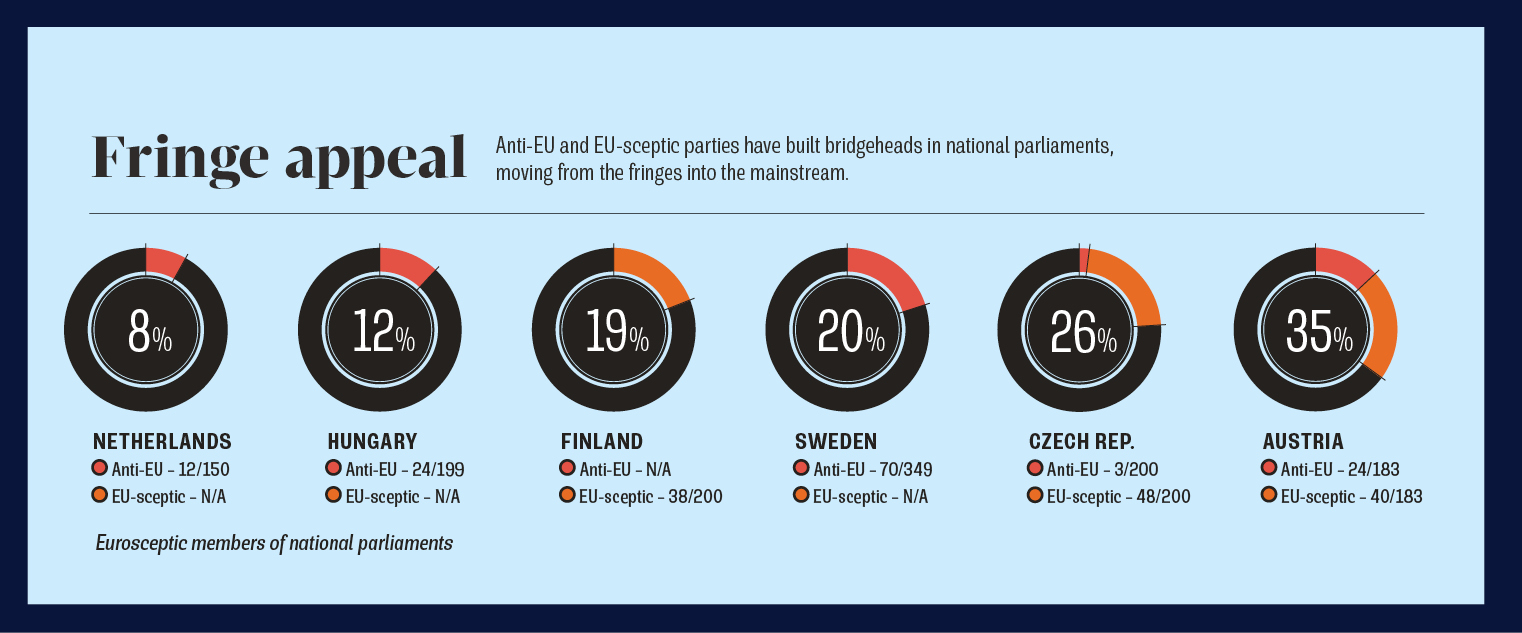

“Euroscepticism”, the awkward catch-all term that has come to represent a wide range of views from outright nationalism through to mild discontent, is still a minority view across the European Union. In national parliaments, many of which have changed since the start of the eurozone financial crisis, anti-EU parties rarely hold the balance of power. Only Denmark’s Danish People’s Party has translated success in Europe into success at home, coming second in national elections in 2015. Broadly, across the EU, citizens are still in favour of the union, but polls show that apathy is on the rise, while in local and European elections, which typically return a higher proportion of fringe groups, nationalists have made gains.

Germany

Germany

When Angela Merkel came to power at the head of a centre-right coalition in 2005, she did so on a platform that included reassuring a German electorate that was fearful of unchecked immigration from Eastern Europe and beyond. Her CDU party was, if not hardline on migration, then certainly true to its roots on the right. A decade later, Merkel oversaw a remarkable policy of opening Germany’s doors to 1 million refugees, setting a progressive example for a continent that was descending into border disputes and recriminations.

The open-door policy has not been universally positive. A mass sexual assault in Cologne at New Year, perpetrated by men mainly of North African and Arabic descent, raised social tensions, and the far right capitalised on the uncertainty and a growing wave of Islamophobia.

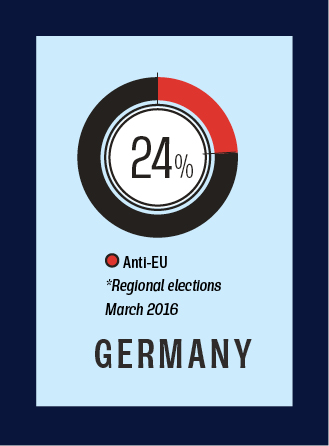

A new, nationalist right-wing party, Alternative für Deutschland, led by Frauke Petry (pictured), who has advocated shooting refugees who try to enter Germany illegally, has attracted many former centre-right voters. At local elections this March, the AfD, which was founded only in 2013, won seats in eight of Germany’s 16 state parliaments and attracted nearly a quarter of the popular vote — second only to Merkel’s CDU. However, the picture is far from simple. In a sign of growing polarisation, explicitly pro-refugee candidates also performed strongly.

Denmark

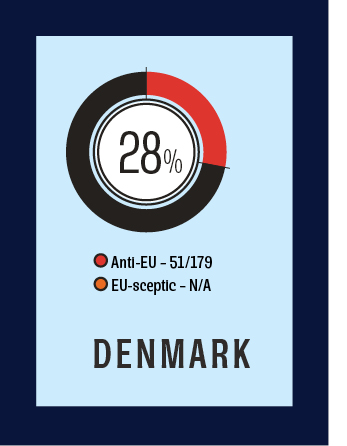

Once a marginal player with a message focused almost entirely on sovereignty and anti-immigration, the Dansk Folkeparti — Danish People’s Party — experienced a startling surge in support in Denmark’s 2015 elections, taking more than 20 per cent of the popular vote and 37 out of 179 seats, making it the second-largest party. DF’s opposition to migration and open borders has resonated with increasing numbers of Danes, and its influence over the more centrist right-wing government has been clear in policymaking, in particular the controversial decision to confiscate the belongings of refugees crossing into the country.

Greece

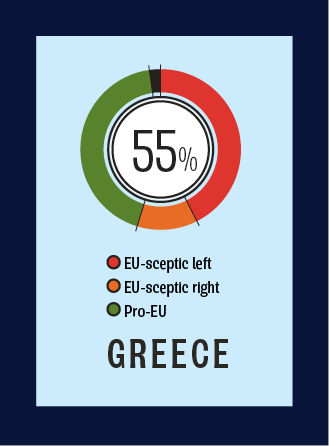

When Syriza, Alexis Tsipras’ anti-austerity, socialist coalition, stormed to power in Greece’s elections in January 2015, European financiers and policymakers lined up to warn of the dangers posed by the party’s rejection of the austerity measures that were supposed to restore the country to solvency. That Greece would essentially volunteer to leave the Eurozone after so many billions had been spent to keep it in seemed unthinkable, but years of recession and massive unemployment have fuelled antipathy on the radical left and on the far right. The neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party came third in the last election, winning 7 per cent of the total vote.