Above: Tate & Lyle’s factory in Silvertown, London, stands as the UK’s only remaining cane sugar refinery – Newscast/UIG/Getty Images

As the political fallout of the UK’s EU referendum vote played out on June 24, veteran farmer Paul Hovesen was worrying about sugar. As the director of farming at Holkham Farms in Walsingham, Hovesen is responsible for the production of a raft of different crops – including beet sugar, which currently enjoys favourable financial protection from the EU. With the UK’s looming exit from the bloc, beet farmers are wondering what this newfound freedom means, and how exposed they will be to the rigours of the free market.

“We will have two things that suddenly have a much bigger influence on our financial output: we are not subsidised in the production and probably never will be, and at the same time there is the danger that huge fluctuations in global sugar prices could have a huge effect,” Hovesen says.

In 2015, the EU paid British farmers roughly £3 billion in subsidies; if those payments are to continue, they will have to come out of the UK budget. Andrea Leadsom, secretary of state for food, agriculture and rural affairs, said prior to the referendum that the UK would match whatever the EU used to give them – although she had previously said that she opposed all subsidies.

EU support has helped UK beet sugar farmers cope with the rollercoaster ride of white sugar prices over the past decade. Although it limits beet sugar’s share of the market to 40 per cent of the total, Brussels has also helped beet producers to crack the monopoly that cane sugar long had over the British market, by putting in place import caps on product entering the union. The UK consumes more refined sugar than it produces, making up the shortfall with imports from France and Germany.

Challenges

The impending challenges for the sugar market underline the complexity of the UK’s trade negotiations post-Brexit. Unless the UK government offers some protections to domestic beet sugar producers, they could struggle to remain competitive after the country leaves the EU. The EU currently puts heavy tariffs on imports of cane from major producers, such as Brazil and Australia; if those no longer apply under whatever trade deal comes out of the UK’s negotiations, the market could be flooded with cheap imports.

Added to this, is the question of whether the UK government can negotiate their way into the single market, which, according to Ben Richardson, associate professor in international political economy at the University of Warwick, is “absolutely the most important [priority] because it will establish how they compete with continental European sugar producers.”

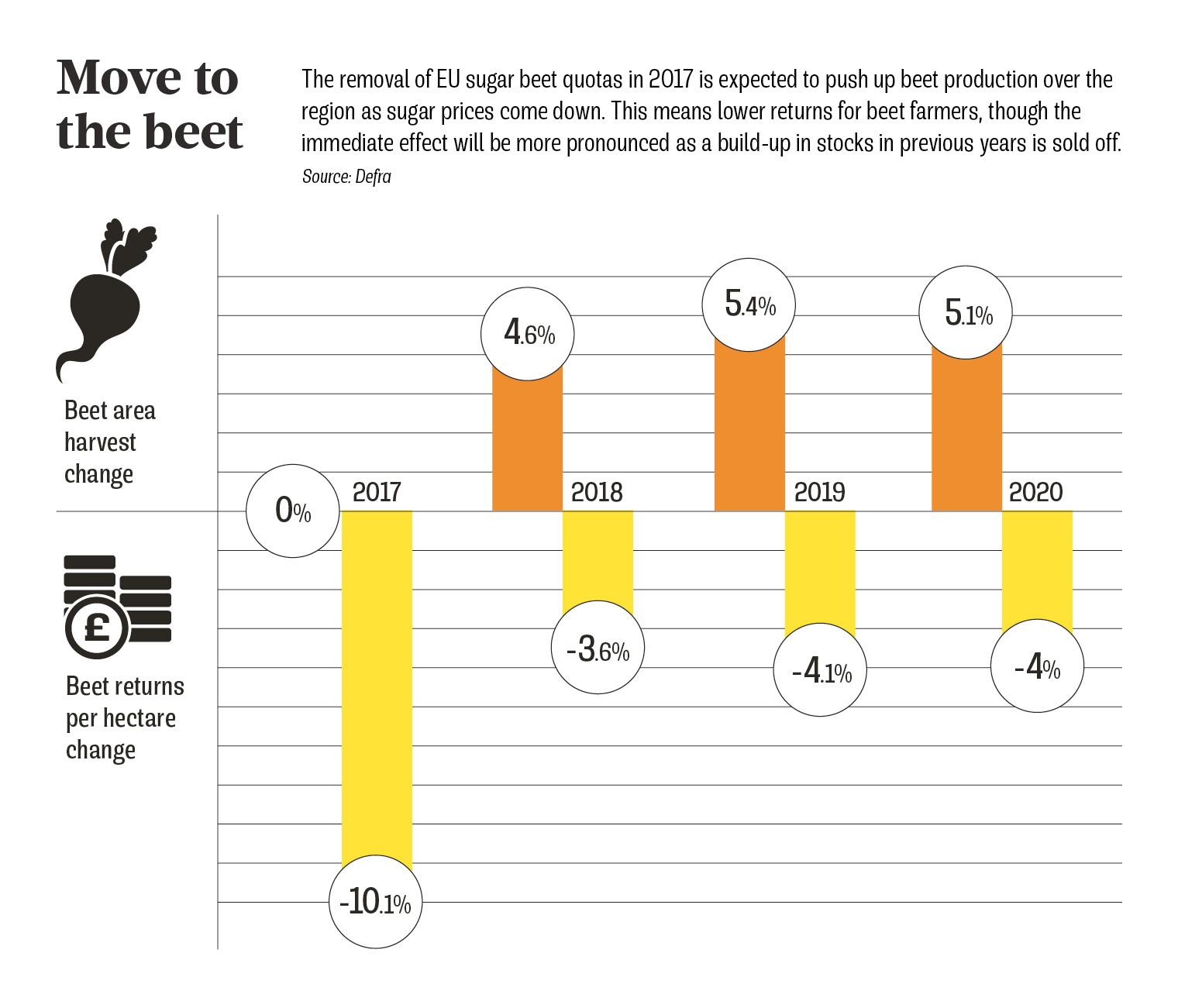

Once Britain leaves the EU, UK beet sugar producers will also miss out on the benefits of reforms to the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy, due in 2017, which will remove beet’s 40 per cent cap. European producers have been preparing to increase their output once the restrictions are lifted.

The big losers from this policy shift will be sugarcane refineries, who will still face the same tough trade restrictions on their product within the EU.

[embed_related]

Tate & Lyle’s behemoth sugar refinery was opened on the banks of the Thames River by Henry Tate & Sons in 1878. At the time, it was one of 75 English sugar refineries, that was supported by the booming colonial sugar trade. Since then, the sickly smell of hot sugar has wafted across East London’s docks. In 2016, the plant stands alone as the UK’s only cane sugar refinery; it now displays a large banner that reads “Save Our Sugar”, which towers over the streets of the East London suburb of Silvertown.

Beet sugar

For decades, Tate & Lyle have argued that the EU’s tough trade restrictions make it near impossible for refined cane sugar to compete with beet sugar. It holds these measures responsible for the reduction of the once dominant cane sugar refinery’s operation to five days a week and its production to roughly half capacity.

In the lead up to the referendum, Tate & Lyle’s senior vice president, Gerald Mason, wrote in a letter to the Financial Times: “There are 19 EU countries that produce sugar from beet and only a handful that produce it from cane. And when the laws for operators in a single EU sugar market are being determined, the pervading mentality in both the European Council and European Parliament is for each member state to fiercely and aggressively protect its own interests.”

Mason also made headlines on the eve of the Brexit vote, when he wrote an open letter to the company’s roughly 800 employees. In the letter, Mason advised Tate & Lyle employees that, while he did not want to tell them who to vote for, he would be voting leave for the sake of the company.

We have a lovely opportunity with policy post-Brexit to have an agriculture that is integrated with production and food security through incentives

Tate & Lyle told Raconteur in a statement: “It will take some considerable time to establish new rules for the UK sugar market. We look forward to working with the government and all sugar stakeholders to design a UK sugar policy that balances the interests of all.”

With Brexit on the horizon, the UK government will need to broker some kind of arrangement between Tate & Lyle and the National Farmers Union, who represent the beet sugar farmers. As Richardson says: “Bad news for beet farmers and British Sugar may be good news for Tate & Lyle.”

Back at Holkam Farms, Hovesen sees a silver lining amid the current uncertainty: the possibility that the UK could figure out a new, smarter subsidy scheme that reduces the need for imported sugar.

“We have a lovely opportunity within the UK, with policy post-Brexit, to give it more imagination and have an agriculture that is integrated with production and food security through incentives,” he says.