Mr Robot is possibly Hollywood’s ultimate hacker show – the chaotically unfolding story of Elliot Alderson, a cyber security engineer with emotional problems, who is recruited by a fiendishly cunning group of hacktivists in their attempt to bring down the fictitious financial giant E Corp.

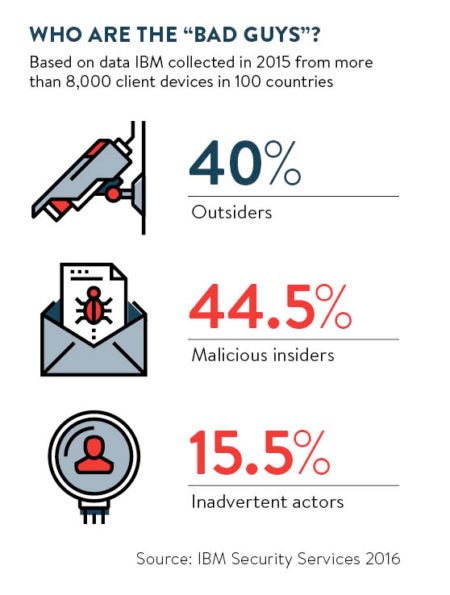

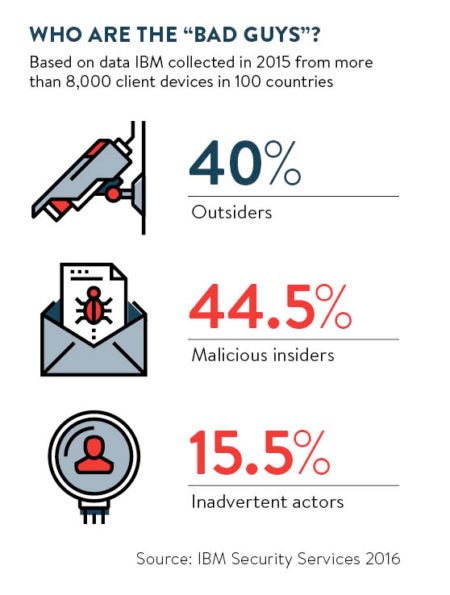

Elliot wears a hoodie and hacks from his bedroom, just like all good movie or TV hackers do. For Mikko Hypponen, chief research officer at the cyber security firm F-Secure, this image is quaint and entirely false. Mr Hypponen looks at 350,000 samples of new malware attacks almost every single day. Some 95 per cent of them are from organised online crime syndicates. Only the tiniest proportion of hacks is committed by hacktivists.

“The earliest viruses were written by bored teenagers looking for a challenge, but today’s hackers are much more malicious,” he explains. “What makes them different from old-school hackers is they have a motive.”

So, what are hackers really like?

This new breed of cyber criminals see themselves as digital mafiosos. The Moldovan hackers behind the Dridex malware attack stole millions of dollars in co-ordinated hits on 300 banks around the world. Evgeniy Mikhailovich Bogachev, the Russian thought to be the author of the Zeus trojan, has a $3-million bounty on his head from the FBI, and is wanted by Interpol and Europol.

This new breed of cyber criminals see themselves as digital mafiosos. The Moldovan hackers behind the Dridex malware attack stole millions of dollars in co-ordinated hits on 300 banks around the world. Evgeniy Mikhailovich Bogachev, the Russian thought to be the author of the Zeus trojan, has a $3-million bounty on his head from the FBI, and is wanted by Interpol and Europol.

That’s not to say naughty teenagers aren’t a threat, says Troy Hunt of data breach aggregation service Have I Been Pwned? “There are teenagers getting hold of vast amounts of personal data, using freely available software, as in the recent TalkTalk hack,” he points out. “Scotland Yard told the press it was a Russia-based Islamic jihadist group, but it turned out to be two teenagers.”

Either way you lose, says Adrian Nish, who leads the Threat Intelligence team in BAE System’s cyber-defence division. Real-life hackers are as good as or even better than movies suggest. A few months ago, Mr Nish explains, hackers targeted the Central Bank of Bangladesh and tried to steal $951 million, six times the amount in George Clooney’s Ocean’s Eleven.

“They set up bank accounts in Manila in the Philippines and in Sri Lanka then broke into the Bangladesh bank network, probably sometime in 2015, and waited until February 4,” he explains. “This was a Thursday, the end of the week in Bangladesh and just before the Chinese New Year, so overall they had this four-day window to get away with the heist. They flipped just eight bits of code, secured root access and covered up the transactions to make it look like the money hadn’t left the bank’s accounts at all.”

This new breed of cyber criminals see themselves as digital mafiosos

Of 35 attempted transactions, only four got through – meaning the hackers stole $81 million rather than $951 million – but it’s still one of the biggest bank robberies in history. “Banks don’t do enough testing,” Mr Nish warns. “We’re dealing with people who’ve been trained to make network intrusions, so the people we have defending our system also need training, also need to know how to spot these types of attacks and how to set up the system security in order to defend against it.”

The human factor

In TV drama, people are a big weak point that hackers take advantage of. In Sherlock, for instance, Moriarty pretends to hack the Bank of England, the Tower of London and Pentonville Prison before – spoiler alert – revealing it was the human factor all along – disgruntled employees, with no super technology needed. And the human factor is definitely key in online security.

“The most sophisticated attacks of recent years had people on the inside,” says Sadie Creese, professor of cyber security at the University of Oxford. “That’s people who work for us, people that are members of our family, our small groups, employees on the books, our business partners, anyone with valid access to some part of our system.

“We all carry sophisticated technology like smartphones around with us and we all work or use the cloud. So now hackers no longer have to hack 20 or 50 organisations. They hack one cloud and they get every single person who is using that cloud.”

Working the people factor is commonplace. “You’ve got to work on five or six different attack factors at any one given time,” says white hat hacker Jamie Woodruff from Metrix Cloud. “My favourite is the viewing webcams on Google. You can locate a specific area, find open cameras and build up a profile about who walks into that infrastructure and who walks out. People follow routine. You see them repeat, you build up a pattern then use tools like Montego, where you can type in key identifiable information then find your eBay account, your e-mail account, your address, your telephone number… then you’re in.”

Popular hacks

Among the tricks Mr Woodruff has pulled there’s setting up fake .eu versions of company sites and asking employees to log in, tailgating into an office with a group of smokers then walking around dropping tainted USBs and sticking up official looking QR codes at business conferences which infect smartphones with malware.

And movies rarely show one of the fastest-growing forms of cyber attack – ransomware, where a hacker locks down all the files on anything from a laptop to an entire company or steals extensive information and demands money to release or return everything.

Moty Cristal, professional negotiator and chief executive of NEST Negotiation Strategies, recalls one banking client receiving an e-mail stuffed with very confidential customer information. Two minutes later, he received a WhatsApp message demanding $120,000.

Mr Cristal adds: “When you’re facing this crisis, it is the human factor that needs to be managed. Making connections and negotiating are essential.”

Although, to be fair, The Negotiator is a whole different movie. Looks like hackers can get into almost everything.

The human factor