1. Money

Financial gain is the daddy of all motives for cyber crime. According to Orla Cox, director of security response at Symantec, people in the UK suffered up to 2,215 ransomware attacks a day in the last 12 months. In most cases, the victim’s data, including important documents, images and video is all encrypted, and access to it denied until a ransom is paid.

Financial gain is the daddy of all motives for cyber crime. According to Orla Cox, director of security response at Symantec, people in the UK suffered up to 2,215 ransomware attacks a day in the last 12 months. In most cases, the victim’s data, including important documents, images and video is all encrypted, and access to it denied until a ransom is paid.

Research by SentinelOne covering 100 chief information security officers whose organisations have been targeted by hackers revealed that 64 per cent believed their attackers were driven by financial gain.

“Most forms of malware in circulation today are meant to make the authors money,” says SentinelOne’s chief of security strategy Jeremiah Grossman. He points to the CryptoWall ransomware, a Trojan horse that locks up files and requests payment for the key. By some estimates it has caused $325 million in damages.

Stealing this amount of money in the real world may be impossible. But not only can criminals take more via virtual channels than they can by walking into a bank with a shotgun, they can hide easily too, usually in territories thousands of miles from where their victims feel the pain. If there’s no such thing as the perfect crime, this comes pretty close.

2. The challenge

The term “hacker” is ambiguous. It doesn’t come with a value judgment attached to it, so technology experts who fall under the definition range from ordinary people who love solving problems with computers to nefarious individuals applying their skills with criminal intent.

The term “hacker” is ambiguous. It doesn’t come with a value judgment attached to it, so technology experts who fall under the definition range from ordinary people who love solving problems with computers to nefarious individuals applying their skills with criminal intent.

What binds these two groups is the thrill of the chase. They relish the chance to pit their wits against each other and stretch the envelope of their abilities. For some this means creating brilliant software in a competitive environment; for others it means concocting an infamous heist.

But a small group doesn’t fit either category. They just want to see how far they can go. To these, a complex security protocol is like a Rubik’s Cube with a thousand sides – a problem too tempting to ignore.

In 2001, British hacker Gary McKinnon began accessing secret files on computers owned by the US military and Nasa. Operating from his girlfriend’s Aunt’s house, he read, manipulated and allegedly destroyed files for more than a year before being apprehended by the authorities.

“The motive for these hackers is simple – breaking something not made to be broken and accessing something never intended for their eyes,” says Paul Briault, director of digital security at CA Technologies.

3. Hactivism

Anonymous, LulzSec, Lizard Squad and Fancy Bears are all groups claiming to campaign for virtuous ends via criminal means. These and hundreds of smaller groups mostly target large organisations. They do so for reasons ranging from exacting revenge for perceived wrongdoing to uncovering security flaws which are then hastily patched up by the victim organisation.

Anonymous, LulzSec, Lizard Squad and Fancy Bears are all groups claiming to campaign for virtuous ends via criminal means. These and hundreds of smaller groups mostly target large organisations. They do so for reasons ranging from exacting revenge for perceived wrongdoing to uncovering security flaws which are then hastily patched up by the victim organisation.

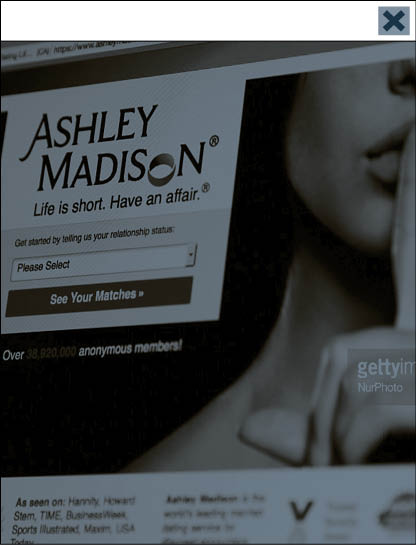

Last year, a group calling itself The Impact Team swiped e-mail addresses and credit card data from the website of Ashley Madison, a dating organisation for married people wanting an affair. It published the data via the dark web and publicly shamed site users.

“The Ashley Madison data breach last year is one example whereby hackers threatened to release details of individuals in a database,” says Paul McEvatt, senior cyber threat intelligence manager at Fujitsu UK and Ireland. “It highlighted the sophistication of cyber criminals and why more needs to be done to combat these multilayered threats.”

In September, Fancy Bears stole and published athlete’s medical data in a bid to “expose the athletes who violate the principles of fair play by taking doping substances”. Meanwhile, in 2011, LulzSec targeted Sony in retaliation for the company’s legal action against hacker George Hotz. It claimed to have compromised one million accounts.

4. Revenge

For some, cyber criminality is a career, for others it’s a moment of rage-fuelled madness. Disgruntled employees, spurned job candidates and people fed up with perceived mistreatment can now exact revenge in the virtual world.

For some, cyber criminality is a career, for others it’s a moment of rage-fuelled madness. Disgruntled employees, spurned job candidates and people fed up with perceived mistreatment can now exact revenge in the virtual world.

Where once they slashed tyres or burnt out a stock cupboard, now the criminally unhinged have the option to bring down a company’s computer systems instead.

In February, a former Citibank employee was sent to prison and fined nearly $80,000 after erasing company data and sending 90 per cent of its network into darkness. Lennon Ray Brown, 38, from Dallas, admitted damaging a protected computer after receiving a poor performance review from his line manager.

Fearing the sack, he shut down the Citibank system. Then he sent a text to a colleague. It read: “They were firing me. I just beat them to it. Nothing personal, the upper management need to see what the guys on the floor are capable of doing when they keep getting mistreated.

“I took one for the team. Sorry if I made my peers look bad, but sometimes it takes something like what I did to wake the upper management up.”

5. Subversion

Orla Cox at Symantec points to a number of recent instances of digital meddling in which espionage and supervision were the likely motive.

Orla Cox at Symantec points to a number of recent instances of digital meddling in which espionage and supervision were the likely motive.

“Earlier in the year we saw a new wave of attacks carried out by two groups, one of which was the Carbanak group, targeting a number of financial organisations. An earlier attack by a different group also targeted financial institutions resulting in hundreds of millions of dollars in losses,” she says. “Carrying out attacks online essentially makes it easier for these criminals to hide their tracks.”

Fancy Bears, the group made famous by their leak of athletes’ medical records, were accused of having links to the Russian state. The motive, it was hypothesised, was retaliation for restrictions imposed on Russian track and field athletes and para-athletes following accusations of widespread doping.

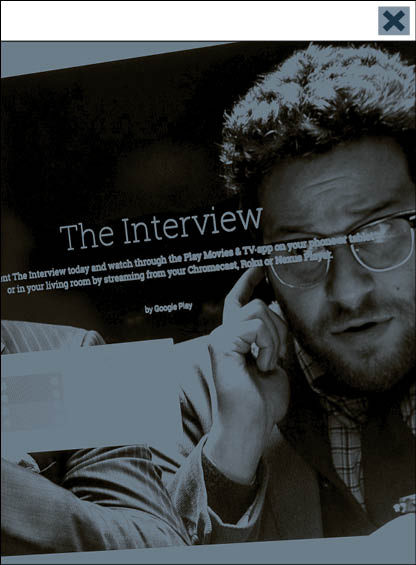

Meanwhile, in November 2014, a group calling itself Guardians of the Peace leaked private information about Sony employees on to the internet, including e-mails, salaries and even unreleased films.

The group launched the attack in response to the Sony film The Interview, which depicted the assassination of North Korea dictator Kim Jong-un. Guardians of the Peace demanded the film withdrawn and even threatened a terrorist attack on theatres.

6. Notoriety

Hacking is a competitive sport and cyber criminals are often motivated by a sense of achievement. If they can pull off the ultimate hack of, say, a global corporation or agency, then the kudos from their peers is huge.

Hacking is a competitive sport and cyber criminals are often motivated by a sense of achievement. If they can pull off the ultimate hack of, say, a global corporation or agency, then the kudos from their peers is huge.

As Jarrod Siket from ThreatQuotient points out: “Some individuals and groups are solely motivated by the recognition that comes with being the first to do something, or successfully disrupting a high-value or highly visible target.”

Paul Briault at CA Technologies agrees. “Putting their name to what could be a globally discussed hack increases their notoriety. Being able to brag about their skillset is of huge value to hackers,” he says.

“Hackers like to show off their intelligence, skillset and ability. Knowing that every business and organisation is attempting to keep them out and away from information only encourages them more. Hackers are often proud to make their presence and accomplishments known.”

Social media platforms such as Twitter have clearly played a part in spreading the word – and the perpetrator’s notoriety – about attacks and in some cases they have even helped co-ordinate hacks.

Although hackers such as Kevin Mitnick and John Draper have gained notoriety, as well as a criminal record, from hacking, most hackers are never famous.

1. Money

2. The challenge