Known as 3D printing because the machines often resemble office printers, additive manufacturing is the physical realisation of digitally designed ideas through the layering of material. It is one of the core innovations transforming the industrial sector as manufacturers embrace the fourth industrial revolution.

The technology involves the breakdown of a computer-designed 3D model into cross sectional layers. Each layer is then rendered by a 3D printer sequentially to build up the part originally designed.

Unlike many other forms of manufacturing, 3D printing is not subtractive; it does not involve removing material from a mass nor the melting and reforming of material. Instead, it only uses the amount required to produce a part.

Building in layers allows all kinds of unique geometries to be created, making 3D printing ideal for producing bespoke or tailored parts. The current output is generally geared towards very specific and specialised requirements.

“Using traditional mass-manufacturing techniques could prove very expensive in these situations,” says Duncan Smith, director of industrial and production solutions at Canon UK. “3D printing is ideal when the outcome of your project is highly specified and low in volume.”

How 3D printing began

3D printing was first developed as a rapid prototyping technique in the early-1980s, but the machines were expensive and complicated. It underwent a series of developments throughout the decade, including the patenting of stereolithography and selective laser sintering processes.

The early-1990s saw commercial adoption as the technology continued to mature, followed by a wave of hobbyist, cheaper 3D printers in the 2000s and growing hype as the technology became mainstream in the industrial sector. In recent years, the products have shifted into the “prosumer” market.

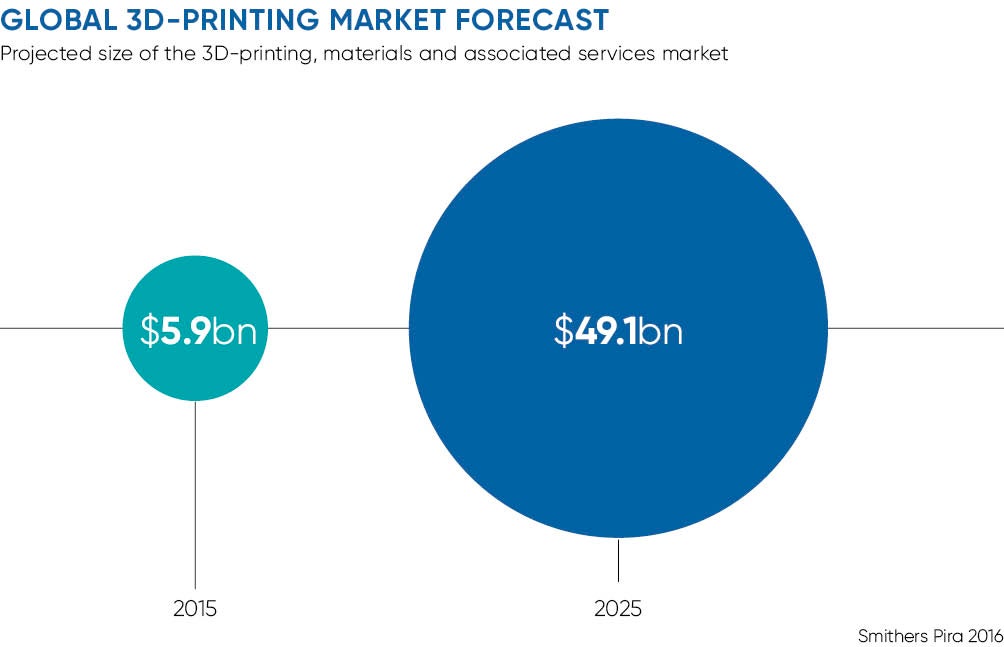

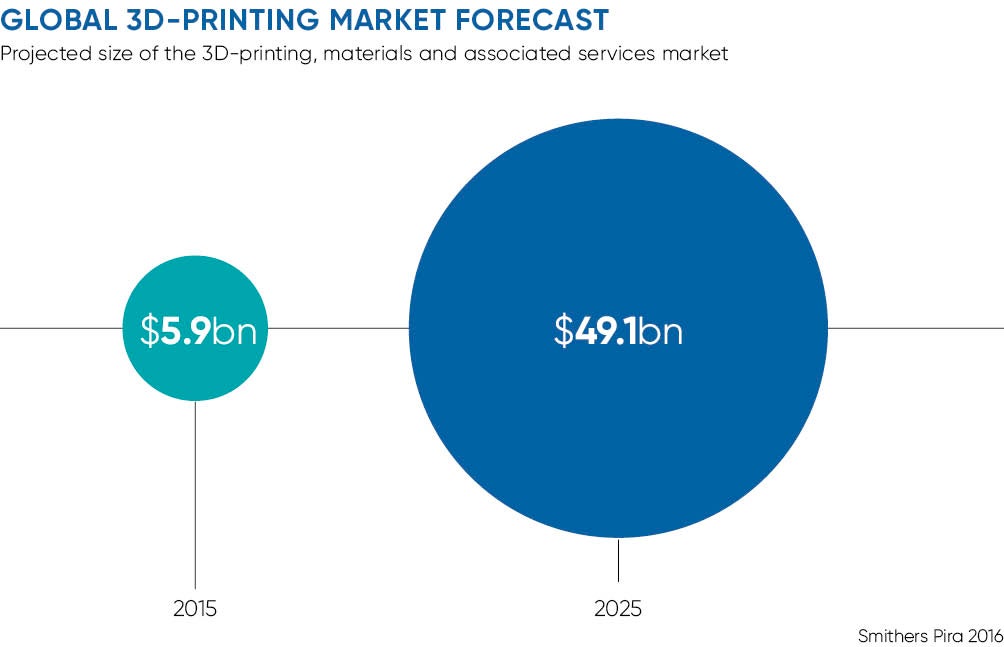

In the last ten years, in particular, the cost of a 3D printer has reduced drastically, from up to £14,000 to around £300, placing it firmly on the radar of manufacturers around the world. IT analyst firm Gartner expects 3D printer shipments will more than double by 2018, increasing end-user spending to $13.4 billion. McKinsey predicts an economic impact of up to $550 billion by 2025.

This is a transformative technology that will play a key role in enabling the new world of advanced manufacturing

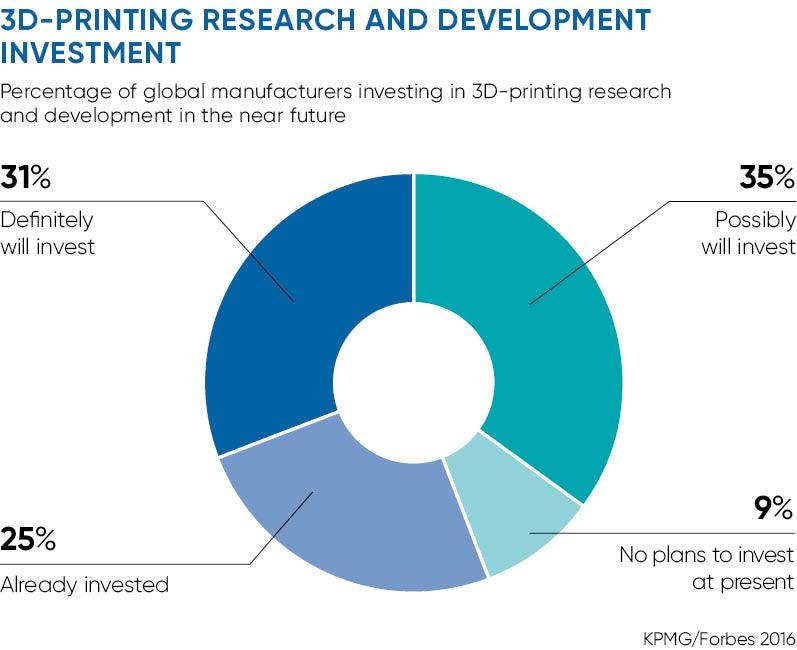

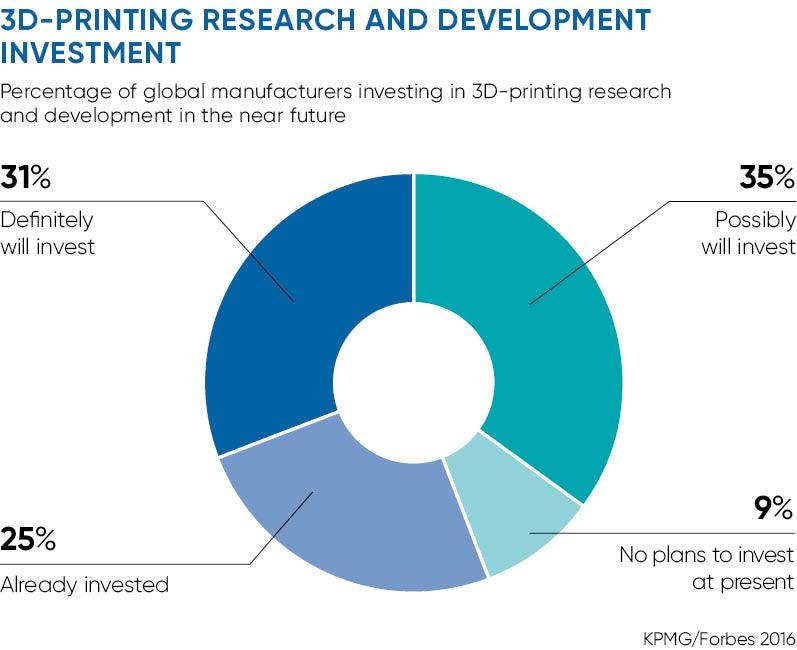

Two-thirds of manufacturers are already using 3D printing in their production systems and 42 per cent expect to adopt it for mass manufacturing in the next five years, according to PwC. Major brands, including BMW, Nike and Johnson & Johnson, are eyeing it up as a means to produce custom parts, while research from Boston Consulting Group anticipates the aerospace, automotive, and medical and dental industries will account for around half the market in 2020.

Perhaps the most well-known adopter of additive manufacturing is multinational conglomerate General Electric, which last year spent more than $1 billion buying controlling stakes in two leading manufacturers of industrial 3D printers, Sweden’s Arcam AB and Germany’s Concept Laser.

GE is using laser-powered 3D printers and other advanced manufacturing tools to make parts and products that were thought impossible to produce using traditional technology. The company is developing the world’s largest laser-powered 3D printer that prints parts from metal powder.

“This is a transformative technology that will play a key role in enabling the new world of advanced manufacturing,” says Mohammad Ehteshami, vice president and general manager at GE Additive.

“Additive manufacturing allows customers to achieve improvements in quality, efficiency and performance of manufacturing operations, and reduction in waste and material consumption. Traditional discrete manufacturing is worth over $15 trillion – if the additive industry replaces just 0.5 per cent of that, it could be a $76-billion opportunity.”

The benefits

Manufacturers seek several benefits when deploying 3D printing. The advanced capabilities of the technology facilitate the realisation of parts with complex features and geometries previously considered impossible to manufacture.

For a business case, the key selling points are time and cost-savings. Product development time is saved through the immediate realisation of prototypes, which can be produced as functional end-use parts.

With parts produced almost as the finished product, the production of bespoke tooling is no longer required. Continual iterations of a design are also more easily achieved, so testing is completed before any investment in tooling.

Damian Hennessey, director of global sales operations at Proto Labs, a manufacturer of 3D-printed custom parts, also points to the associated environmental benefits. “There can be less wastage of material compared to other manufacturing techniques,” he says.

3D printers must now overcome their own hype and up their speed if mass manufacture is to be achieved. Until then, companies are more likely to complement their current manufacturing facilities with one or two 3D printers, rather than overhaul their processes.

A gradual adoption allows manufacturers to build the knowledge required for large-scale use. “The majority of engineering courses still offer very little, if anything, in way of additive manufacturing content and that needs to change,” says Philip Hudson, UK managing director at Materialise, a 3D-printing solution provider.

This gap in additive manufacturing skills will have to be filled before the true potential of 3D printing is realised, but until then it will continue to gain momentum for producing parts in low volume for specialised applications.

How 3D printing began