If digital is a revolution, the chief digital officer or CDO is a revolutionary. Mobile connectivity and real-time data updates have created an always-on, ever-changing electronic environment. It is fundamentally different to the information technology revolution of the 20th century, which automated existing process. It is also a change that is affecting every organisation, from the government’s Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) to financial services firms.

Mayank Prakash, director general for digital technology at the DWP, says: “To give you an example, carers need to meet us, but time is a luxury they cannot afford. So we have turned that interaction into an online digital service which means they can interact with us whenever they want. That often means outside the classic nine-to-five boundary, and not from PCs but from tablets and mobile devices.”

Philippe Denis, CDO at BNP Paribas Securities Services, says the financial services provider is looking at robotics, natural language processing and artificial intelligence as three key game changers.

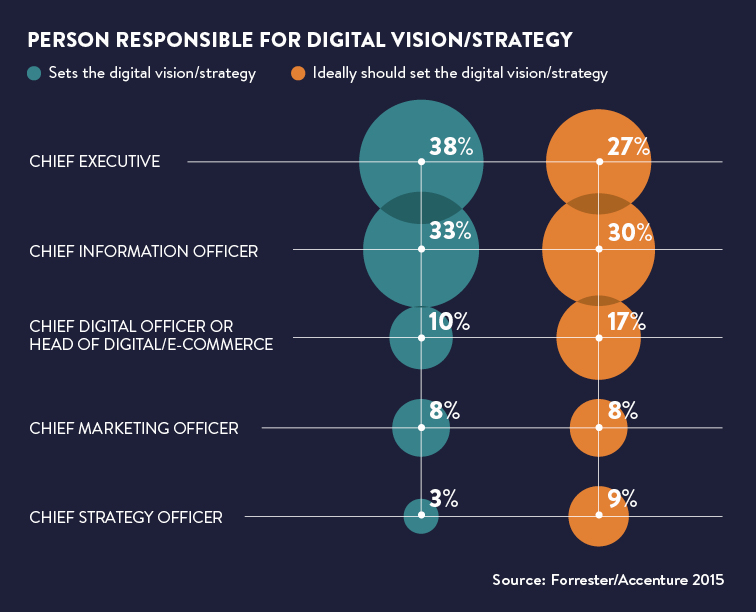

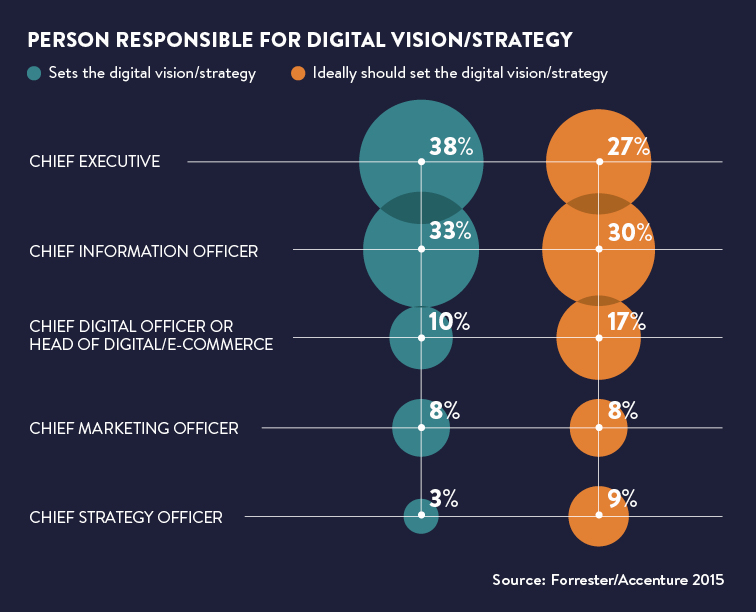

“What are we going to give our employee of tomorrow to be more efficient?” he asks. “Across industries, implementation of new technologies is typically six years. Some things are going to pop up quickly, six months for a prototype, six more months to one year for implementation. These are new transforming topics. The chief executives and chief information officers (CIOs) of this world cannot add this to their plate. That is why the new world of the CDO has been created.”

Increasing number of CDOs

In its report Adapt, disrupt, transform, disappear: The 2015 chief digital officer study, consultancy PwC found that business-to-consumer (B2C) firms were the most likely to have someone in the post of CDO, with firms in communications, media or entertainment (13 per cent) topping the list, while business-to-business (B2B) firms such as automotive, engineering or machinery (3 per cent), or metal and mining (1 per cent) were the least likely. The 2015 Harvey Nash CIO Survey, published in association with KPMG, supported this dynamic, noting that manufacturing and utilities were three times less likely to be disrupted by digital technology than broadcast media.

The overall number of CDOs has grown considerably over a short space of time. The Harvey Nash report found that 17 per cent of CIOs worked with a CDO in 2015 up from only 7 per cent in 2014. Some 5 per cent of CIOs were reported to be hiring a CDO in 2015.

The tasks of the digital chief are balanced across changing process, technology and culture

“If you looked at a lot of those CDOs, they were not technologists, they were business individuals,” says Lisa Heneghan, partner in the KPMG CIO advisory practice. “I think the role is a balance. Some organisations will bring in business-focused individuals and drive most of the technology components down a level within the organisation. Others will bring individuals who embrace the business dynamic and build on their technology background. I don’t think one or the other [is right]. It depends on the organisation.”

Being a head of digital does not always require the CDO moniker, but it is crucial that the process is managed at a senior level. Claire-Louise McSherry, managing director of executive search firm McSherry Brown, reports there has been an upsurge in requests for CDOs where chief information and technology officers had traditionally been sought.

“When the landscape changes, people can be more comfortable creating a different label,” she says “A chief digital officer can look across an organisation and bring it forward to meet its current needs.”

The three streams

The tasks of the digital chief are balanced across changing process, technology and culture. Mr Prakash identifies two streams, that of “going digital” which is focused on working with customers online using digital channels so they have greater control over the interaction with us, and “being digital” by using better automation to make an organisation more efficient and thereby provide better services.

Darren Price, chief information officer at insurer RSA, is responsible for digital within his company. He recognises those two streams and believes each requires the head of digital to address specific challenges.

“The first is how to drive commercial and business outcomes through digital,” he says. “How do you get the digital agenda to the top of the business list? That drives customer service and retention. The second piece is internal digitisation. How do we provide a quality end-to-end service for our customers internally around work flow and standardisation?”

He also identifies an important third element that must be addressed – innovation. Failing to innovate can be very expensive, especially when other firms are able to step in and disintermediate. Some industries, including music and media, have seen profits decimated by the effect of digital on distribution. As the head of digital at a large wealth manager noted: “In the early-2000s, Sony owned a huge portfolio of music licences and portable music technology, yet Apple is the firm we talk about dominating music downloads.”

Online allows new businesses to break down established relationship networks. From iTunes to Spotify to Amazon, the traditional chain of intermediaries is being pushed to one side, and publishers and producers have seen margins slashed. Other industries are looking at that effect closely and working out how to avoid a similar fate.

“For many organisations the interesting issue around data is how they can monetise it,” says Ms McSherry. “They have a lot of information, but many do not understand the intelligence this can give them.”

Key to that is the capacity for a company and its staff to change with the times. Intrinsic within that is how best to manage the skills gap. Depending upon the sector, different organisations can find themselves severely challenged in attracting the top talent.

Boston Consulting Group, which describes the new digital industrial transformation as “Industry 4.0”, found in a recent study of German and American businesses across industries that 38 per cent of firms considered the lack of qualified employees as a big or very big challenge to adopting Industry 4.0, some 30 per cent rated it as an intermediate challenge and just 11 per cent thought there was no challenge.

The DWP’s Mr Prakash says his organisation is uniquely positioned to attract talent, likening it to a massive startup. In part he believes new employees are interested in working in the public interest that the DWP aims to deliver and in part due to the scale of its business, which gives even people working for the big digital native firms a suitable challenge.

He says: “We process £170 billion in payments every year, we manage £1.7 trillion in pension funds, on an average day we share ten million data records with over 400 organisations, so the size of what we do is off the scale for any other industry.”

Increasing number of CDOs