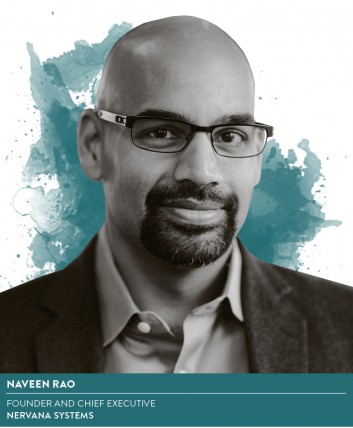

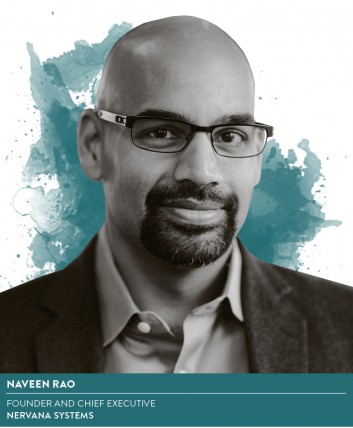

It was in 1996, part way through his undergraduate degree at Duke University in North Carolina, that Naveen Rao decided to take a course in artificial intelligence. That was also the year in which IBM’s Deep Blue became the first computer to defeat a chess grand master when it won a game, but not a whole match, against Garry Kasparov.

It was in 1996, part way through his undergraduate degree at Duke University in North Carolina, that Naveen Rao decided to take a course in artificial intelligence. That was also the year in which IBM’s Deep Blue became the first computer to defeat a chess grand master when it won a game, but not a whole match, against Garry Kasparov.

There was a buzz around the discipline at that time but, as Naveen says, it had “a very different flavour back then – I would describe it as ‘creative algorithms’.”

In 1997 Deep Blue managed to beat Kasparov over the course of a whole six-game match, but some things were still beyond the reach of AI. The game Go, for instance, in which the first move offers 361 possibilities, compared with 28 in chess, and can last for 150 turns, compared with around 80 in chess, was thought to require too many computations to be tackled to a high level by a computer.

“Go was too complicated,” says Naveen, who would go on to gain a PhD in neuroscience before founding his own AI company, Nervana. “It was something that we just didn’t touch. We thought, ‘Brains do something magical that we just don’t understand – we’re not going to go there’.”

But then, earlier this year, it happened. AlphaGo, a program developed by a London-based subsidiary of Google, beat the world champion Lee Sedol four games to one in a five-game match.

‘We’ve discovered that brains aren’t that special; they do heuristics and pattern recognition very well – that’s ‘the magic’’

“Less than 20 years later [the problem] has been solved,” says Naveen. “That’s pretty huge to me.” The crucial breakthrough has been a result not just of increased computing power, although, of course, that has helped, but thanks to advances in a particular kind of AI, known as deep learning.

“The method allows computers to process tasks through ‘neural networks’, systems that mimic the structure of the human brain in order to learn, improve and, in the case of AlphaGo, become capable of decision-making that resembles human intuition more than it does brute computation.

“We’ve discovered that brains aren’t that special; they do heuristics and pattern recognition very well – that’s ‘the magic’.”

But, of course, AI isn’t just about board games. Naveen points out that programs relying on deep learning are already commonplace. “It’s pervaded many experiences. Facebook has about 1.6 billion active users every month; every one of those people is taking advantage of deep learning in the news that’s fed to them and the auto-tagging capabilities [which recognise faces in photos].

“We almost take it for granted now and are surprised when it doesn’t work. That transition happened really fast.” Apple’s Siri and Google Assistant are among deep learning’s other everyday applications.

If the technology is pervasive in one sense, in another its use is restricted, often the preserve of Silicon Valley giants that have the resources and expertise to take advantage of it.

That’s why, since it was founded in 2014, Naveen’s company has set about using the $24 million of investment it has received to make the benefits of AI more widely available.

Nervana works with companies’ data science teams to provide them with access to its deep learning “cloud”, and to develop and run programs that make the best possible use of the reams of data they have accrued. The firm has helped various clients to make intelligent robots for farming, spot fraudulent financial activity or analyse photographs to pinpoint likely locations for oil deposits.

It’s crucial work, Naveen says, because it allows companies to get to grips with what he describes as “the biggest computational problem that we have today”.

“If we gave 100 megabytes to every man, woman and child every day, which is a lot, if it’s text, it would take us 30 years to get through all the data we have right now. And that problem is getting worse by the minute. In ten years we expect there to be 75 to 100 times the amount of data we have today,” he says.

Beyond giving companies access to Nervana’s neural network hardware and its expertise, Naveen is planning to provide a further solution by developing a computer chip that is specially designed for the demands of deep learning. By doing so, he posits that the time it takes to “train” a neural network to perform a certain task could drop by as much as tenfold, enabling a process that currently takes weeks or months to be completed within days or even hours.

This, presumably, is part of the reason that Nervana was one of the first companies to be backed by Playground Global, the incubator-cum-workshop set up by the creator of Android, Andy Rubin, after he parted company with Google.

‘If you take a machine that has been designed to learn from data and optimise complicated processes, it probably won’t have the motivation to destroy the world’

However, the pace of change in the field has also given rise to concerns. Elon Musk, the founder of Tesla and SpaceX, has likened the threat of uncontrolled advances in AI to “summoning a demon” and named it as humanity’s “biggest existential threat”, which sounds not unlike the dystopian “rise of the machines” scenario imagined in Hollywood’s Terminator film franchise.

Since making those remarks, Mr Musk has teamed up with Stephen Hawking and other leading scientists to pen an open letter about the potential dangers of AI and, last December, founded OpenAI, a research organisation that aims to develop the technology while taking careful steps to keep it under control.

“I actually talked with Elon about this and he’s a very thoughtful guy,” says Naveen. “The headlines can make out that he’s fearful of the future, but he is saying, ‘Well, let’s at least have a conversation and talk about the possibilities that could be bad for humanity and try to take actions now that will help us steer away from those things.’ I think that’s a very practical thing to say.

“I actually talked with Elon about this and he’s a very thoughtful guy,” says Naveen. “The headlines can make out that he’s fearful of the future, but he is saying, ‘Well, let’s at least have a conversation and talk about the possibilities that could be bad for humanity and try to take actions now that will help us steer away from those things.’ I think that’s a very practical thing to say.

“We are working with OpenAI and thinking about the ethical implications, but most of the research is not about building a sentient computer or one that has desires. It’s about better automating processes that humans have learnt to do, so it’s still a tool under our control. If you take a machine that has been designed to learn from data and optimise complicated processes, it probably won’t have the motivation to destroy the world.”

But what about more prosaic concerns, such as the instability of the economy and labour market that could be caused by the automation of millions or even billions of jobs that human beings currently count on to earn a living?

Naveen doesn’t deny the possibility exists but, understandably, would rather frame the shift in a different way. He says: “The fear is that they’re going to take all our jobs away, but they’re basically giving us bigger tools. It’s like a bulldozer for data – I can make sense of much larger swathes of data than I could before and use that to be more competitive in my company.”

Deep learning is already being used to create programs that exhibit “creativity”, something that would have traditionally been considered the preserve of humans. An application called Jukedeck can create original, royalty-free music when given specifications regarding the length and style of the piece it is instructed to compose.

“But it’s going to be hard for a machine to actually understand the experience of a human for a long time,” says Naveen. So it’ll be a while before Jukedeck will know whether it should be proud of its latest work.

Naveen mentions Facebook, Google and Chinese tech giant Baidu, which he says has developed the best voice recognition software in the world for both English and Chinese, as some of the leading proponents of deep learning. Drones and automotives are, he thinks, among the most exciting areas, but he also name checks Swype, the app which allows users to write whole words on their smartphone keyboards with just one small continuous movement of their thumb. Conversely, he sees less practical value in the Swiss-based Blue Brain project, which seeks to create “biologically detailed digital reconstructions” of a human brain.

That raises a question. Looking to the future, is it possible that neural networks and AI, mirroring the structure of the human brain, will be surpassed by something else?

“Evolution works in layers; it doesn’t come up with a whole new solution all at once,” Naveen concludes. “As a neuroscientist studying the brain, you can see that it’s basically a hack upon a hack upon a hack. At this point, the human brain is the best exemplar of a computer that we have in the world, but there are better paradigms out there.”

Right now the next step might seem too far away to consider. But then, 20 years ago, the same could have been said about a computer beating the world champion of Go.

CASE STUDIES: BLUE RIVER AND PARADIGM

Agriculture startup Blue River has taken advantage of Nervana’s deep learning cloud to improve the way it manages its crops.

The company used a system to “phenotype” plants, recording various pieces of data such as height and age which are reliable predictors of future development, to make instantaneous decisions about how to thin their fields to optimise yields.

However, the system was prone to errors because of complications that reduced the reliability of the computer vision systems within the machines used to perform the task. For example, weeds could not always be recognised by the system and so would often result in inefficiencies.

Nervana’s Neon deep learning system was able to pinpoint the single pixel within a 812 x 612 pixel image where the stem of a plant met the ground and, as a result, added a greater degree of precision to the crop-thinning process. Nervana says its methods were used to help Blue River improve yields by up to 10 per cent.

In another venture, Paradigm, which provides software solutions to the oil and gas industry, partnered with Nervana on an initiative that helped the business to locate viable sites through automated image scanning.

By processing a vast cache of 3D seismic images, the program was able to detect subsurface faults, folds and other geological features that tend to trap oil. Increasing the efficiency of image scanning has a knock-on effect that leads to more targeted drilling, which in turn leads to reduced costs.

“We approached Nervana Systems to explore ways artificial intelligence could help improve operational efficiency in oil exploration,” says Indy Chakrabarti, senior vice president of product management and strategy at Paradigm. “Nervana successfully built a deep learning-based solution on their cloud to detect numerous subsurface faults within three-dimensional seismic imagery without the need for manual intervention. Nervana cloud enables geoscientists to spend less time on repetitive tasks and become more productive.”