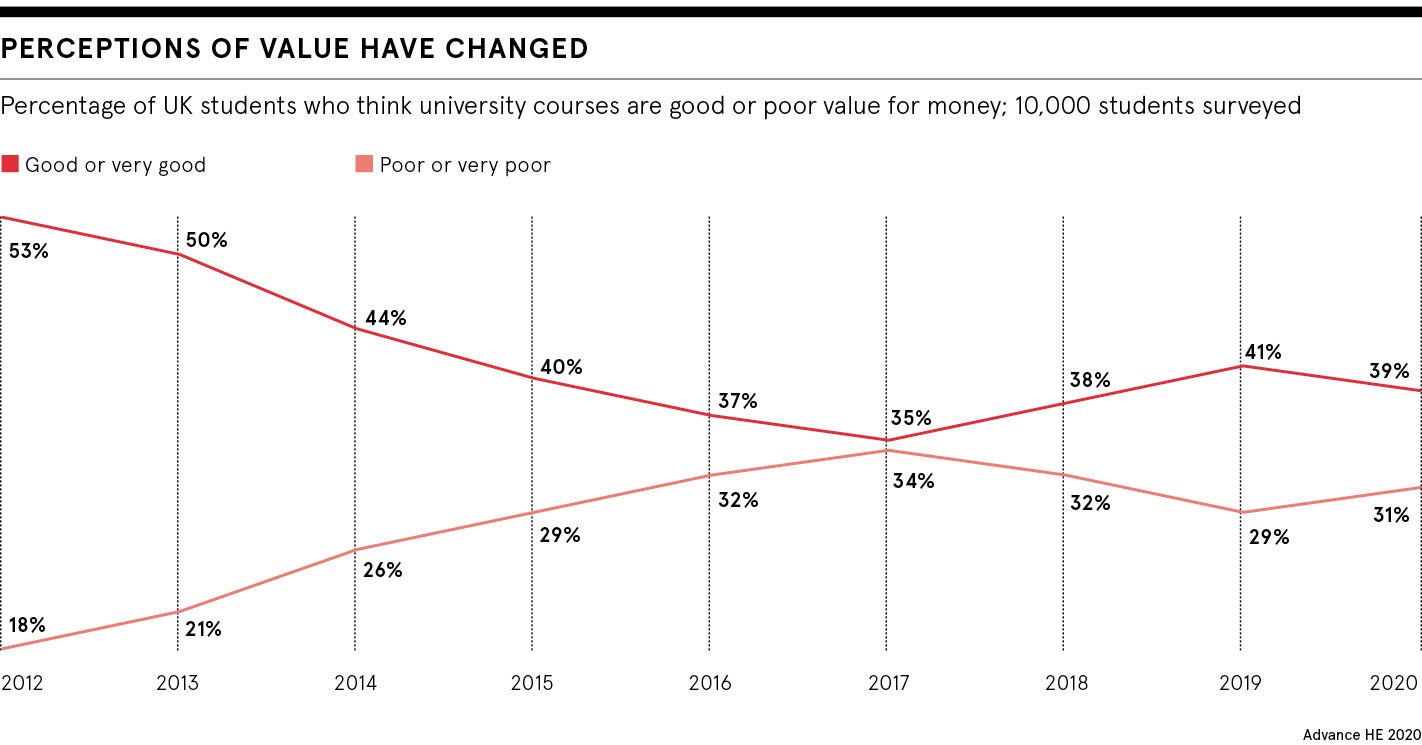

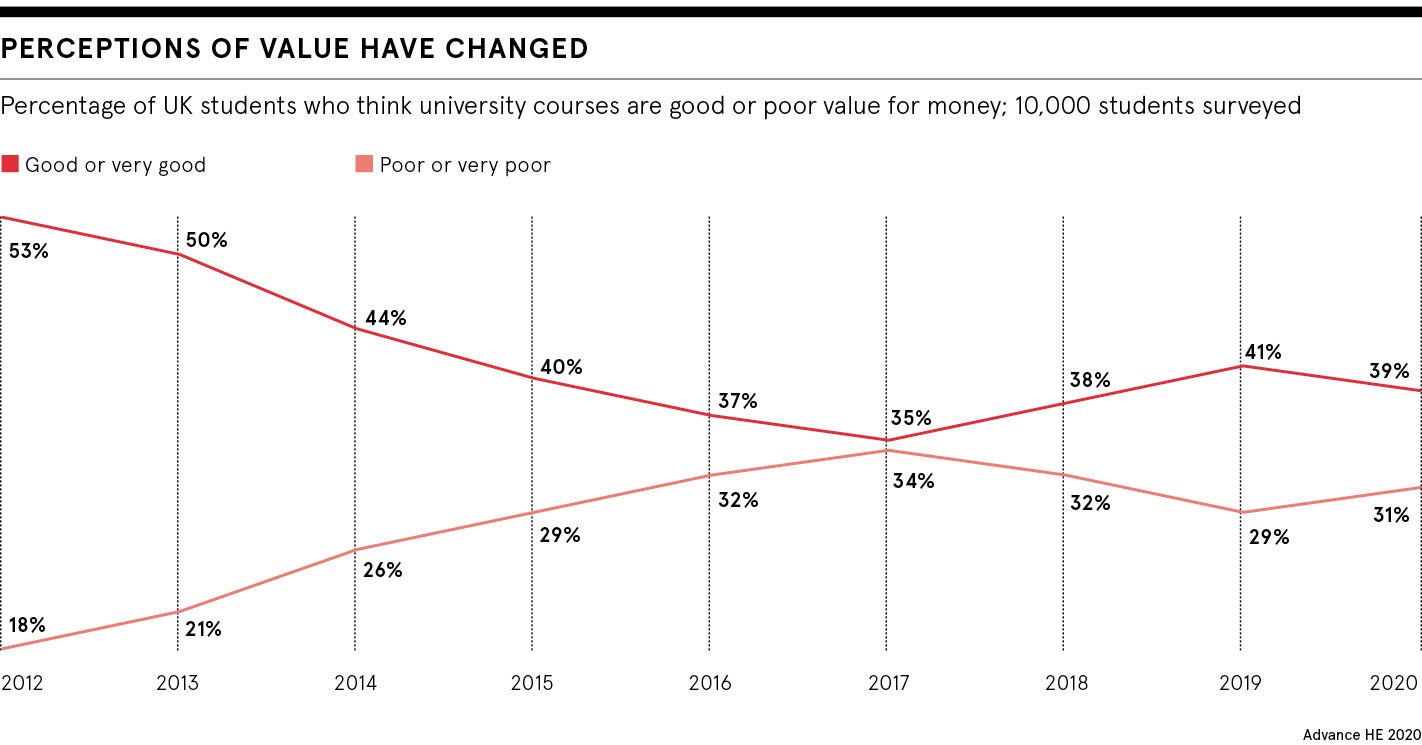

Student outrage at the refusal of universities to offer automatic refunds for no-go lecture halls underscores the bitter debate on the fundamental aim of university education and return on investment for the fees-burdened coronavirus generation.

While Boris Johnson’s government is currently holding the line on the existing university business model, which has triggered close to £50,000 in average student debt and unanswered questions around value for money, calls for reform have come from some unlikely bedfellows.

Former prime minister Theresa May has made no secret of her desire to see both a cut in tuition fees and a return to maintenance grants for the poorest students. Her disquiet is shared by Labour peer Lord Adonis who, despite having helped design the current methodology, described the universal £9,250 fees levy as a “cartel”.

While support for an Australian-style, differential system based on subject has grown, the potential downgrading of any course to second best could jeopardise graduate employability.

Higher education in crisis

“It is inevitable that students see themselves as consumers and therefore feel short-changed by the limiting of face-to-face contact time, but to treat higher education as just another marketplace is to miss the point,” says Jo Grady, general secretary of the University and College Union (UCU).

“To create a sustainable university business model and preserve the aim of university education for learners and society as a whole, we need a more progressive approach to all forms of taxation and a closer look at corporation tax. And yes, we are totally in favour of the abolition of tuition fees.”

With the Open University celebrating more than 50 years of successful remote teaching, cheaper, online-only degrees would seem an obvious way for bricks-and-mortar providers to quash damaging claims of misselling.

Yet to Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) director Nick Hillman, such a move in the current economic climate would be damaging to the higher education sector as a whole. “Back in July, the Institute for Fiscal Studies suggested that around a dozen UK universities would face serious financial hardship without an emergency government bailout,” he says.

“The prospect of reducing fees by £2,000 or £3,000 this autumn to reflect student disquiet over online learning would threaten the ability of these institutions to continue as going concerns.”

University businesses in jeopardy

When the coalition government, led by David Cameron, tripled tuition fees to £9,000 in 2010, universities waxed lyrical about the “all-round university experience” which boosted social, personal and intellectual growth as well as earning potential.

Yet to the 350,000 students who unsuccessfully petitioned the government for a full 2019-20 refund to reflect cancelled lectures, labs and field trips, along with prolonged strikes and unused accommodation, the aim of university education post-pandemic is less clear.

Many students may this autumn decide to take their chances in the job market rather than shell out £9,250 a year for what some fear will be a succession of pre-recorded lectures and follow-up Zoom calls.

But the notion that person-to-person teaching via live seminars and tutorials, or students hanging out socially, is now a thing of the past is laughably wide of the mark, says Professor Tansy Jessop, pro vice-chancellor for education at the University of Bristol.

“It’s already been said that 2020 will be the best time to start a degree and having seen the levels of student engagement being achieved with blended learning, I can only agree,” she says. “At its best, online learning is more personalised and inclusive, and promotes a feeling of community that is impossible in a crowded lecture theatre where social interaction is nil.”

Wider benefits of university will be clearer

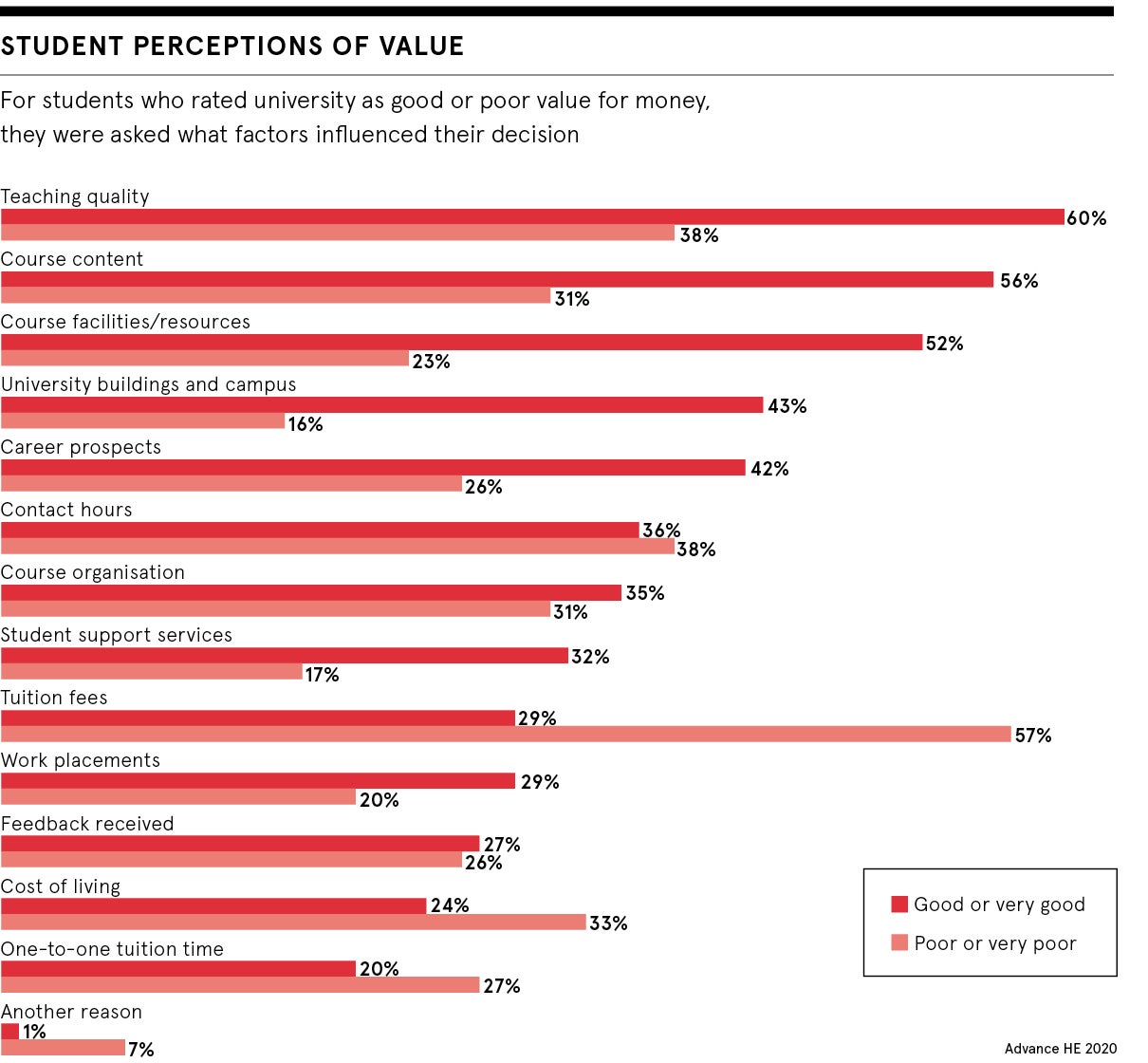

The move away from passive listening to a “more active and two-way learning experience” must, she says, be factored into any discussion around value for money. As always though, the best costs.

“To preserve the aim of university education, we are applying a rigour to online teaching which quite possibly costs as much if not more than the traditional lectures and seminars model,” says Jessop. “While I agree that compound interest rates on student loans are unethical, I think it’s fair higher education ‘consumers’ should pay something towards a life-changing rite of passage which only around half the population will ever get to experience.”

Regardless of the edict that refunds cannot be automatic, a growing number of universities have already, albeit quietly, compensated learners for disruption. While Hillman at HEPI says he fully supports reimbursements for students who feel “promises have not been kept”, he cautions against making claims based solely on person-to-person contact hours.

“When lectures have been cancelled, many students have accessed other facilities such as the library or sports halls and it’s important to recognise too that the wages bill for higher education, which amounts to some 59 per cent of total cost, isn’t reduced by limited contact time,” says Hillman.

Yet in the period since April, UCU’s Grady estimates that some 30,000 to 40,000 university staff on fixed-term contracts have been shed and she fears that without them the fresher experience of 2020 can only be downgraded further.

University business model remains controversial

Professor Steven Jones at the University of Manchester believes the current, market-led university business model does little to support the aim of university education overall. Speaking in a personal capacity, he says: “Defenders of the current market system will point out that the number of disadvantaged students accessing higher education has gone up, as has demand overall, and they’ll also say most graduates will never repay their loans in full.”

While he notes that all of this is true and universities need to be funded in some way, he calls for a new system based around “public good, with universities acting collaboratively and in the best interests of all young people”.

With the current situation of “high learner fees and high interest rates” now untenable, in his view, there is “an opportunity for government to rethink the entire role of universities and their value to society as a whole”, Jones concludes.

Higher education in crisis