The public sector lags far behind private enterprise when it comes to moving legacy IT systems into the cloud, something brought into stark relief by the coronavirus pandemic.

As councils, police forces, schools and hospitals have faced unprecedented challenges, they have had to find, implement and scale solutions at breakneck speed.

Those still using inflexible on-premise IT systems have found it harder to cope than their cloud-native peers. Not only is it more difficult to buy and “plug in” new cloud solutions, they are also likely to have missed out on considerable savings gained from moving to the cloud, leaving them with fewer financial and human resources to throw at the crisis.

“If all your energy is spent keeping the lights on and limiting IT failures, you can’t focus on new initiatives that might transform your operation,” says Rahul Gupta, cloud expert at PA Consulting.

The benefits of cloud in the public sector

One organisation that largely bypassed these issues was Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust, which serves more than 50,000 patients on Merseyside and across the UK.

Working with the IT digital transformation partner Fortrus, it had spent the previous few years moving all its paper health records onto a new digitalised system hosted on Amazon Web Services, which enabled clinicians to access patient data far more quickly.

Not only was this more efficient and secure – previously records had to be manually retrieved from storage by a dedicated team – it also meant the hospital was in a stronger position for a shock it could never have foreseen.

“Without a digital records system it would have been a logistical nightmare. Instead they were able to reconfigure hospital workflows without the risk of physical paper records and porters transmitting the virus,” says Jon Atkin, chief operating officer at Fortrus.

“They could also keep regular tabs on patients who had been sent home, but were still sick, and tackle the crisis as it unfolded.”

In 2014, the UK government made it mandatory for central government departments to consider potential cloud solutions before any other option when procuring new IT services. It also strongly recommended the policy should be adopted by the wider public sector.

Why has cloud adoption been so slow?

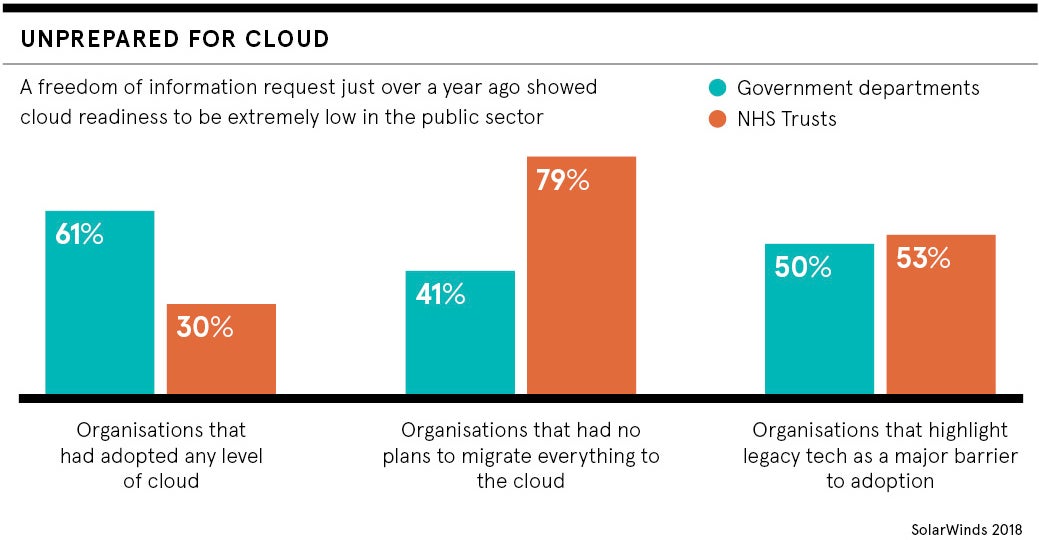

But according to a freedom of information request by IT management company SolarWinds last year, only 30 per cent of NHS trusts had adopted any level of public cloud in their organisation, while the figure for central government departments was 61 per cent.

The pandemic has surfaced some game-changers that people are going to want to hang on to

This will not have helped in 2020 as vast numbers of public sector employees have started working from home, where they need secure remote access to centralised data on various devices. Organisations have also had to scale up IT systems at record speed, for example to cope with a large rise in unemployment claims or to underpin wholly new services such as COVID testing centres.

However, the crisis has succeeded in strengthening the case for change, says Gupta. “The pandemic has surfaced a lot of hidden problems, but also some real game-changers that people are going to want to hang on to when this is over.”

Local councils leading the way

One such success story is Haringey Council in London. Before the pandemic, it was already working to improve in-person collaboration across the organisation through its Agile plan. But in March it had to take the whole project online, a move that has uncovered new ways of working which should outlast the pandemic.

The council had already implemented Microsoft 365, a cloud-based collaboration tool, so was able to move many of its staff seamlessly to remote-working arrangements. It also identified and quickly implemented a range of online tools to aid collaboration, including an online whiteboard with virtual post-it notes, an online polling tool to capture feedback and preferences in real time, and the virtual meetings app Microsoft Teams.

“Being able to adapt our Agile approach in this way helped the council to respond in the early stages of the pandemic by running virtual workshops with groups of staff, residents and communities to understand the impact COVID-19 was having on our communities,” says Andrew Rostom, head of programmes and transformation at Haringey Council.

“Staff have also been able to meet up, share data, collaborate and learn together in a manner almost equivalent to that offered within a physical room.”

Dennis Vergne, who runs the public sector management consultancy Basis, and worked with Haringey on Agile, has seen this sort of innovation more widely and expects it to last, not least as a way to cut costs.

“A number of local authorities went through something like this before the pandemic, but we’ll see more. Putting apps and data into the cloud allows more of your staff to work from home or hot desk and this allows you to get rid of property or leased buildings that are costing the earth,” he says.

“You’ve also seen councils replacing old legacy systems with more flexible, cheaper and secure software in the cloud models.”

Changing culture is the first step to innovation

The problem many organisations face is that they invested heavily in on-premise systems years ago and are still locked into expensive contracts with the suppliers that built them. The prospect of undertraining complex IT migration also scares many.

However, IT managed service companies such as Fortrus say they are breaking this mould by transitioning public sector organisations from legacy single-vendor systems onto more flexible wrap-around solutions. In such cases, clients pick from a wide range of different software vendors, safe in the knowledge they will integrate seamlessly in the cloud.

The pandemic has left many public sector technology departments with shaky finances and an impetus to try new ways of working. Gupta believes it could be the catalyst many need to finally make a concerted jump to the cloud.

“In the public sector, changing the culture is usually much harder than changing the technology. But the pandemic is changing culture very fast. People who were scared to make that jump are now seriously thinking about it and allocating budget,” he concludes.

The public sector lags far behind private enterprise when it comes to moving legacy IT systems into the cloud, something brought into stark relief by the coronavirus pandemic.

As councils, police forces, schools and hospitals have faced unprecedented challenges, they have had to find, implement and scale solutions at breakneck speed.

Those still using inflexible on-premise IT systems have found it harder to cope than their cloud-native peers. Not only is it more difficult to buy and “plug in” new cloud solutions, they are also likely to have missed out on considerable savings gained from moving to the cloud, leaving them with fewer financial and human resources to throw at the crisis.