As companies of all shapes and sizes race to accelerate their digital transformation strategy, one important question weighs heavy: what is the future for the spare humans and how do we prevent the creation of a digital underclass?

Just months into the coronavirus pandemic, everyone from chief executives to government ministers and employment charity leaders have seen the impact of digital transformation on people as well as operating models.

Last year a report from the Office for National Statistics found that out of the 19.9 million jobs analysed in England in 2017, 1.5 million people were employed in jobs at high risk of automation. That was well before the current expert predictions that the economic fallout of coronavirus could see up to five million people put out of work.

Chetan Dube, chief executive at IPsoft, an American multinational focused on artificial intelligence (AI), cognitive and autonomic solutions for enterprises, is well aware of the risks. “There will be some people who will struggle for different reasons to master digital skills and this risks them becoming a digital underclass,” he says.

“Business and human resources leaders who know employees will be displaced should start thinking now about the partnerships they can form with industries that rely on more innate, human capabilities rather than digital skills.” He highlights the example of elderly care, which could be a potential home for out-of-work contact centre workers given their interpersonal and customer care skills.

“It’s so important that the private sector assumes its responsibility, as much as that of the government and public sector, to help those who can’t be reskilled within their own companies to find work with their existing skillsets,” says Dube.

Why digital upskilling is crucial

As chief executive of the WEA, the UK’s largest voluntary sector provider of adult education in England and Scotland, Simon Parkinson oversees a body of students of whom 44 per cent are on income-related benefits, 38 per cent live in disadvantaged post codes, 41 per cent have low or no previous qualifications and 47 per cent are over 60.

Parkinson explains that with 11.5 million UK adults lacking basic digital skills and the country losing out on £63 billion in GDP from its existing digital skills gap every year, the challenge is stark. But he believes solving it starts with supporting people to build their confidence “to try something new without fear of criticism”.

It’s important that the private sector assumes its responsibility to help those who can’t be reskilled within their own companies

The challenge, he says, is not only knowing which digital skills workers will need for a certain job, but also how employers will expect them to deploy those skills.

“Digital upskilling is a necessity for everyone. But it is not an end in itself. It is about understanding how to use technology to achieve goals, which usually have nothing to do with the technology itself,” says Parkinson.

“So much involves having digital skills to even allow you to engage effectively in the job market let alone in employment, from a practical point of view, enabling people to search online for jobs, create CVs and complete online applications to open up a world of opportunities.”

Of course, many other socio-economic factors will come into play. In large parts of the country, internet connectivity is still not at super-fast levels or affordable if it is. Supposedly everyday things that many take for granted are also out of reach for too many, including being able to pay for sufficient mobile data each month or even owning a compatible device.

Increasing access to prevent digital underclass

Nicola Inge, employment and skills director at Business in the Community (BITC), is working hard to prevent a digital underclass growing from the impact of digital transformation. BITC wants employers to remove the barriers and systems that keep opportunities available only to certain groups and people.

“For example, in our programmes to ensure opportunities for development are available to older workers, we are already seeing an impact. We’ve seen a difference between those on our Bristol Accessing Experience programme, who don’t have access to devices, lack credit to top up and/or digital skills and haven’t been able to access the new online content, to those in Northern Ireland who typically have fewer barriers to work,” says Inge.

But she warns: “For groups facing barriers to work, such as ex-offenders, homeless people and refugees, there’s a strong risk that, as the labour market is flooded with newly unemployed people and competition for jobs intensifies, they and other marginalised groups may find themselves once again at the bottom of the pile.”

What is the government’s responsibility?

While many cite the responsibility businesses have, there is also a political imperative too. In 2017, a report released by the European Commission revealed that 44 per cent of Europeans aged 16 to 74 do not have basic digital skills.

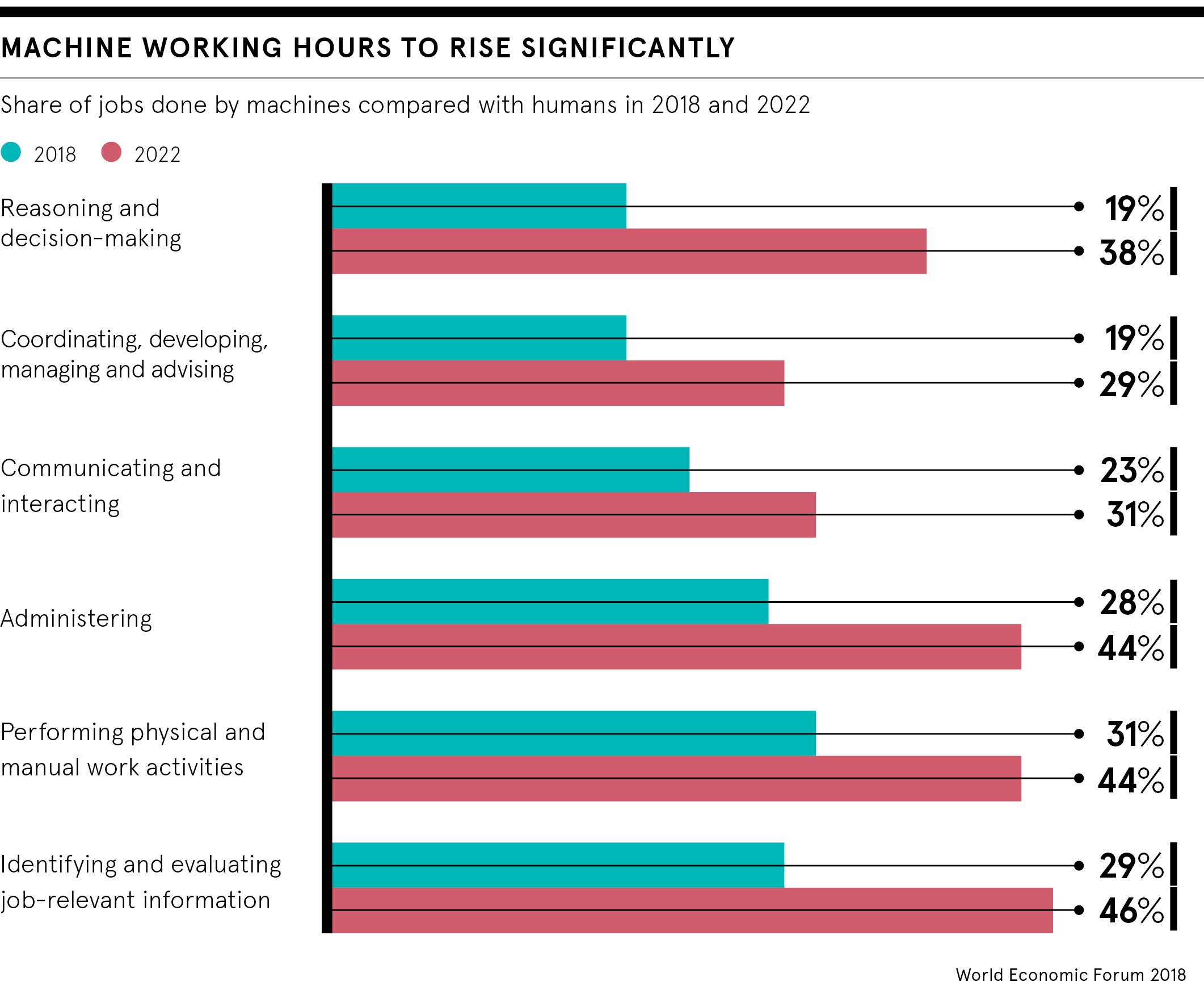

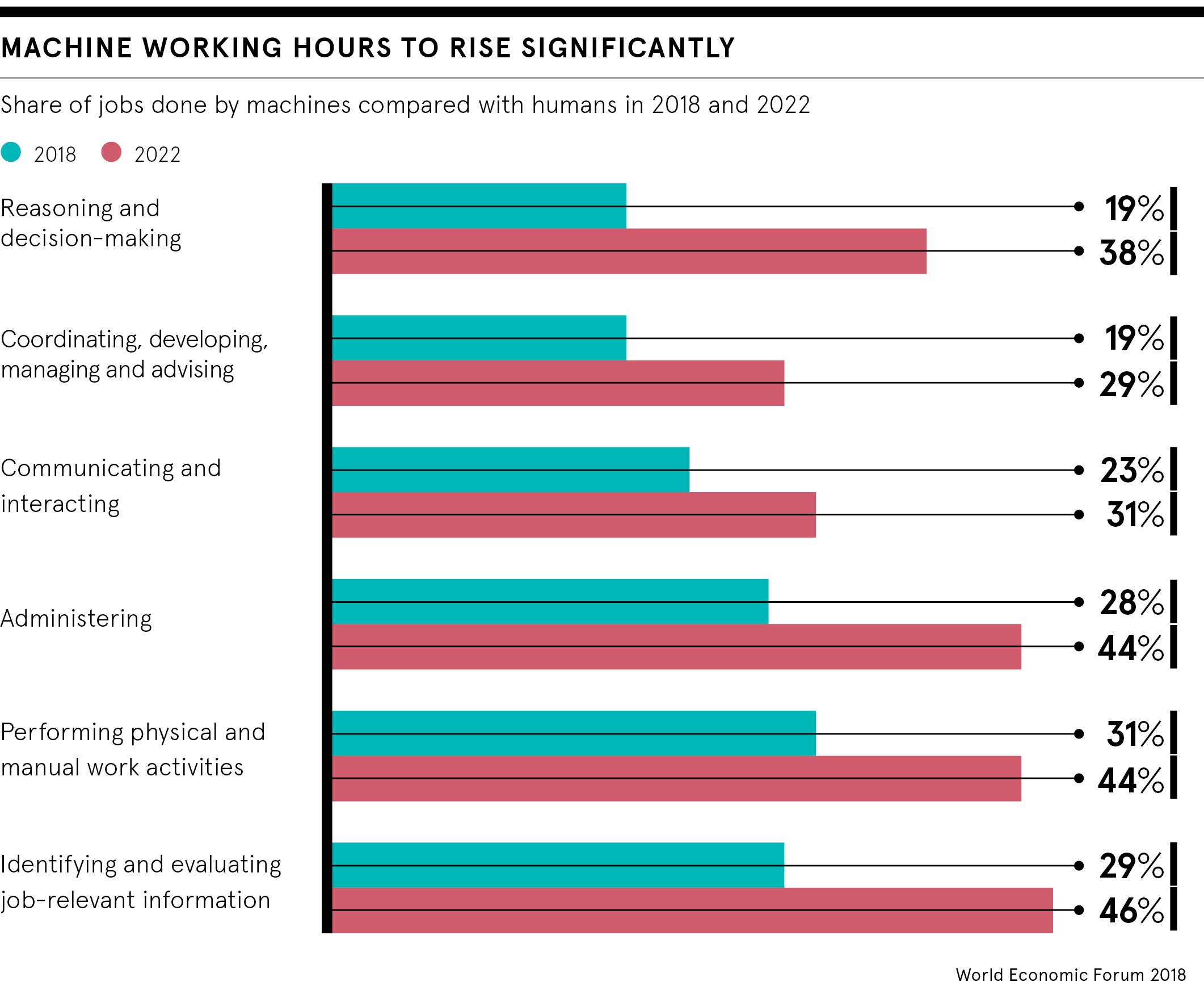

Earlier this year, the World Economic Forum launched the Reskilling Revolution Platform to provide better jobs, education and skills to one billion people in the next ten years. Its own predictions were that 75 million jobs could be expected to be displaced due to automation and technological integration. But it offset the job losses, saying: “The transformation will also create demand for an estimated 133 million new jobs with vast new opportunities for fulfilling people’s potential and aspirations.”

And in its March Budget, the UK government promised a National Skills Fund worth £2.5 billion to drive down inequalities and gaps, but it remains to be seen if the huge hole in the public finances from COVID-19 support measures will hit this.

Bold solutions to employment challenges

Other organisations are playing their part too. The Nesta CareerTech Challenge aims to uncover bold solutions to future employment challenges. And in Birmingham, a £5-million digital retraining fund from the West Midlands Combined Authority was established to pay for digital training for up to 1,900 people over the next three years. This includes adults in low-paid employment, those with autism, under-represented BAME (Black, Asian and minority ethnic) communities and people suffering poor mental health.

Helen Horner, chief executive of charity Digital Anthropology, remains optimistic of preventing a digital underclass if the right funding can be found and there is a focus on retraining people in areas that can’t be automated, enabling them with softer skills such as empathy, emotional intelligence and resilience.

“We need investment from the AI, robotics and machine-learning developers to enable us to fund educational courses, especially for those individuals who do not have university-level education and whose jobs have already been displaced or are at risk,” she says.

“Through ongoing research, we will guide individuals towards retraining and upskilling for occupations at least risk of automation. Demand for shopworkers is declining rapidly as a result of COVID-19, but they have social skills and interaction skills that with additional training could be used, for example, in healthcare roles which are increasing.”

Fred Flack, head of talent academy CloudStratex, believes there must be a partnership approach between government, business and education providers. He says: “We need more bold thinking. Whether you are a startup, small or medium-sized enterprise, or multinational, there is an important role for you to play in preventing the emergence of a digital underclass.”

Why digital upskilling is crucial

Increasing access to prevent digital underclass