Results of the Indian census in 2011 were telling. The United Nations heralded it as a revelation that far more people had access to a mobile phone than a toilet. The signs that the country was transforming digitally were evident then.

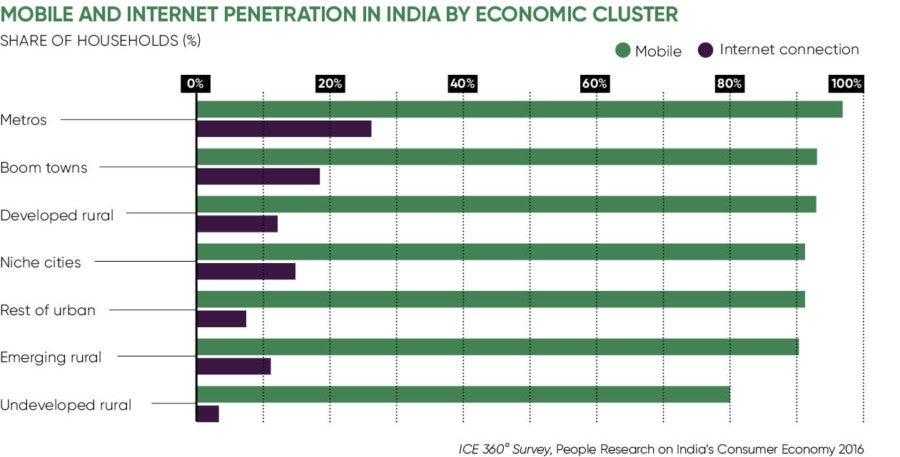

Six years on and the gap has widened. Even more households – 88 per cent – now have access to digital devices, according to the ICE 360° Survey, that’s still a lot more than have running water or decent sanitation.

Whether you’re living in a high-rise block in Bangalore or a smallholding in Manipur, getting hold of a smartphone is easier than ever as the price of handsets and tariffs are both falling. It’s no wonder that access to 21st-century technology has been called “the great leveller for the citizens of India”, by Dinesh Malkani, president of Cisco India.

The Indian telecoms market is now the second-largest in the world after China in terms of subscribers, which is why there’s been a huge rush towards creating a digital ecosystem for its citizens.

Prime minister Narendra Modi’s Digital India campaign faces serious challenges, such as poor digital infrastructure in remote regions

It’s also been backed by prime minister Narendra Modi and his so-called Digital India campaign. The idea is to improve digital infrastructure and internet connectivity in a bid to offer better government services, education, finance and geographical information systems to name a few of the services being rolled out.

“The most dramatic achievement of the current government has been to increase the number of people with a bank account and if the same political heft is put to increasing internet access, particularly smartphones, it’s possible,” says Gareth Price, senior research fellow at Chatham House.

The Indian telecoms market is now the second-largest in the world after China in terms of subscribers

However, the challenges are vast, accessing remote regions from the high Tibetan plateau in the north to the low Sundarbuns in the east with broadband or mobile signals is no small feat. Out of a population of 1.3 billion people, fewer than 400 million have access to the internet, according to the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India. More than 75 per cent of these connections are in the top 30 cities. Penetration is certainly patchy.

“Around 50,000 villages in India still do not have reliable mobile phone access or broadband; connectivity in rural areas is still a work in progress,” says Neel Ratan, partner, government and public sector, at PwC India.

“The challenge around connectivity, literacy and many regional languages also presents a huge opportunity to bring a vast majority of India’s population into the digital fold. However, this large population, when empowered digitally, could help India take the winning leap from being a developing economy to a digital leader.

Considerable progress has been made in certain areas and one scheme that’s the poster child for a digitised India is its biometric ID card or aadhaar. More than 1.1 billion IDs have been issued so far, to 86 per cent of the population. This framework can support many official applications, especially when combined with smartphones.

More than 285 million bank accounts are now linked to an aadhaar number. “This is a solid foundation for a digital economy. The consumption of services has seen a threefold jump over the last two years. More than 100 billion digital transactions for government services were recorded in 2016,” says Mr Ratan.

Aadhaar biometric ID cards have now been issued to 86 per cent of the population

All that India has to do is look at China to see the potential. Here 450 million people can now use their phone as a digital wallet and such services were accessed more than a billion times last year. It has transformed banking and purchasing behaviour. Now financial technology or fintech in China is moving into investments, lending and insurance.

“The most significant area for me would be the apparent attempt to shift India towards a cashless economy, given the recent demonetisation initiative,” says Mr Price. “If the government is intent on shifting towards a taxed, cashless economy then this could transform government revenues since digitisation should serve to reduce the potential for corruption.”

Help is on its way from the commercial sector. China’s innovative fintech companies, such as Ant Financial and Alipay, are expanding into the Sub-Continent.

“We have seen both companies focused heavily on India, on the e-commerce side, on the payment side as well. They’re flushed with cash and they’re increasingly looking at overseas markets,” says Zennon Kapron, founder of Kapronasia.

Ant Financial is valued at $60 billion, about the same size as UBS, Switzerland’s biggest bank. The first mover advantage will certainly come from China into South Asia.

The digital tide is turning in India, albeit slowly. The biggest winners will be its citizens able to use a whole raft of new services. Four of the top five financial technology firms are in China. Expect developments in India too. The sums add up.