Technology tipping points are hard to predict. The first time drones were used in battle was the Vietnam War when the bulky, difficult-to-control Ryan Model 147 Lightning Bug reconnaissance drones were deployed by the US military. The programme was mothballed in the 1970s, then re-emerged in the early-1990s, claiming their first kill in 2001, over Kandahar in Afghanistan. The first commercial drone permit was issued five years later, but it took another five years and smartphone technology to create a real market.

By performing a variety of aerial imaging and sensing tasks, drones could detect problems with equipment on the production line or even the environment that it’s operating in

Many people working in the drone industry were originally flying hobbyist aircraft, powered by electric motors and lithium-polymer batteries, making them lighter, quieter and more reliable than military jets. Cheap smartphone microcontroller chips initially provided autopilot software for these planes. The final stage, according to Professor Dario Floreano, director of the Swiss National Robotics Centre, was the price of accelerometers, used as tilt sensors in smartphones, coming down rapidly. Suddenly a cheap quadcopter that knew its orientation and direction of movement was possible.

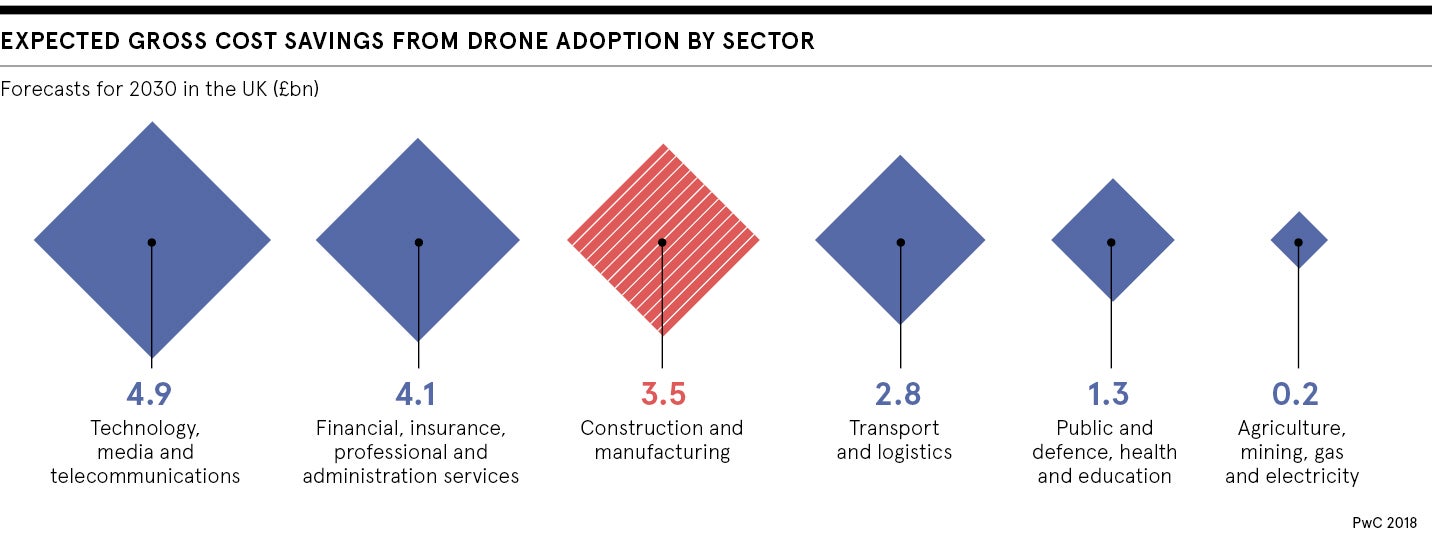

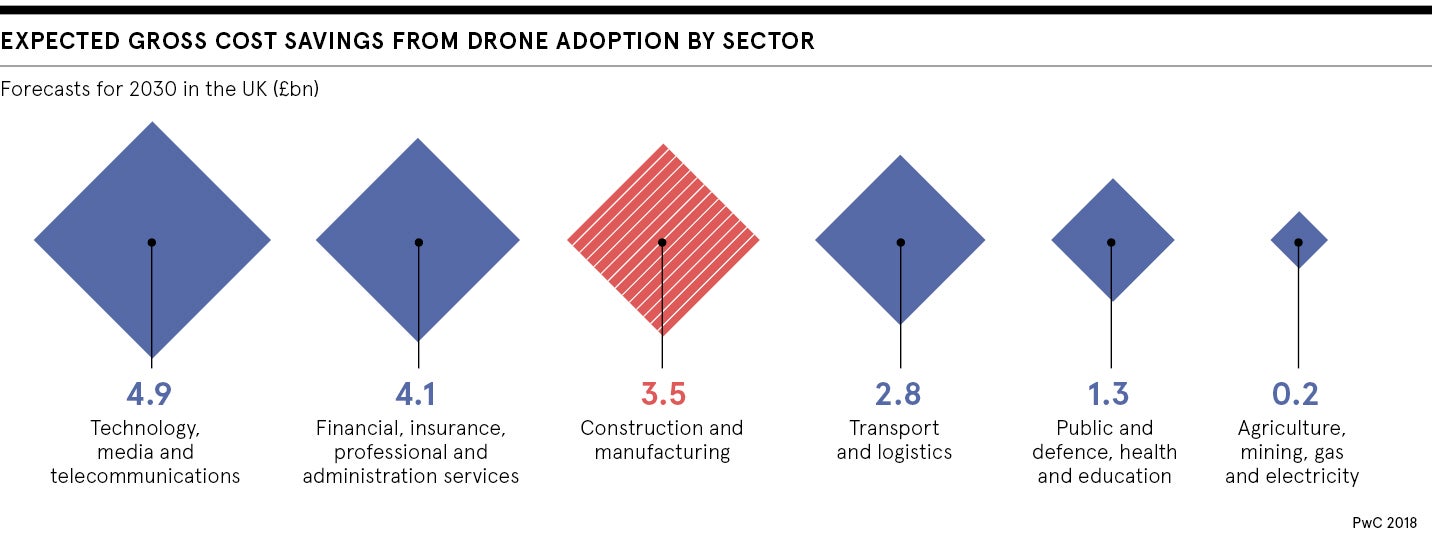

Also like smartphones, people soon started thinking about bringing drones into the workplace. In 2013 Amazon announced its plans for a drone-based delivery system while in 2018 management consultancy PwC set up a dedicated UK drones team and predicted the market for work carried out by drones could be worth a whopping $127 billion worldwide. And yet, given that sales of commercial drones last year were just $2.4 billion, according to Gartner, the question is: are drones really going to transform the way many companies do business or are they just another overhyped fad?

Drones slowly making their way into business

Silicon Valley is backing the tech. “Whenever you see more automation with less weight, like the trends in battery size that’s driving the drone market, it’s worth keeping an eye on,” says Philippe Botteri, London-based partner at Accel venture capital and an early backer of Chinese drone platform startup DJI. “While flying cars are almost a sci-fi joke, battery tech has reached the stage where I can throw eight rotors on a drone and carry four people around. It’s as significant as the driverless car.”

At the moment, the heaviest commercial users are in entertainment and photography (42.9 per cent) and real estate (20.7 per cent), according to a survey from BI Intelligence. Industrial uses come in at roughly 25 per cent of which manufacturing accounts for just 1.5 per cent. The problem is that high-speed automotive assembly plants can be as complicated for drones as a battlefield, from robots that shoot welding arcs to machinery that can interfere with drone communication.

Nonetheless, drones are already being deployed in asset-monitoring, checking inventory by scanning radio-frequency identification chips and barcodes, and visual inspection. The most obvious area for growth, according to Jonathan Wilkins, director at EU Automation, is to expand drones capacity for doing what they’re best at, recording information in ways that are too difficult, dangerous or boring for humans.

“Drones should have a positive impact on quality assurance,” he argues. “By performing a variety of aerial imaging and sensing tasks, such as those using infrared and thermal technology, they could detect problems with equipment on the production line or even the environment that it’s operating in.”

How drones are being used for monitoring and inspecting

Oil and gas companies are already replacing helicopters with drones for routine pipeline inspections. Last June, Shell vice president Hilary Mercer announced the company was using drones to help build its new $6-billion US ethane cracker plant in Pittsburgh. The drones take “thousands and thousands” of pictures of the site on a weekly basis. In August, carmaker Ford began deploying drones to perform difficult inspections on overhead gantries that had previously required shutting down production to complete safely. The drones also give Ford a clear plant maintenance record.

To improve inspections, drone manufacturer 3DR has started adding infrared cameras, initially for firefighting drones, according to Jim Merrick, director of marketing for Qualcomm’s internet of things business. He believes the monitoring drones could be a crucial part of factory health and safety in the near future.

Indeed, the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) began using drones for inspection last year. Similarly, OSHA not only used drones to inspect unsafe areas, it also used them for technical assistance in emergencies and during compliance assistance activities.

Drones about to take off in manufacturing

Compliance presents drones’ biggest problem. Although Amazon’s plan to use drones for home delivery appears to have hit a regulatory hurdle, in November car technology manufacturers ZF became the first company in Germany to use drones to fly spare parts, such as sensors or control cards, from the central warehouse to work areas. ZF’s six-motor drones carry up to five kilograms and fly over the roofs of plant buildings, only crossing driveways where there is no alternative.

Audi is developing a system known as Paula, which follows a defined route set on a navigation system, but also picks up on any obstacles with laser scanners, intelligently working its way around them. Meanwhile Ocado, the UK online grocer, is building a robotic warehouse in the south of England for the French retailer Casino in which pre-programmed drone caddies move along metal rails sorting and moving goods.

Jamie Dargie, vice president at Design Group, points out that drone technology is still in its infancy. He expects to see them fulfilling more roles, from loading pallets through picking and packing to replacing sedentary robots in the manufacturing process itself. Drones in manufacturing, he concludes, are about to take flight.

Drones slowly making their way into business